You Don’t Have the Right

In this Age of Appeals, you have the paper right. And a stamina test.

Your card declines at the grocery checkout.

Your benefits don’t show up.

Your account is suddenly “under review,” or

A letter arrives announcing a decision you didn’t know was being made.

Most people have lived some version of this. In each case, the change is instant, but the “fix,” if it comes at all, lives somewhere behind: hold music, web forms, “high volume,” and a promise that someone will look at it.

Some of this is especially significant in high-speed, high-stakes systems. Power used to look like ‘a decision maker.’ Now it looks like an undo button you don’t get to press.

I’ve come to believe our political center of gravity has to move from who makes the decision to how hard the decision is to reverse.

Fast harm, slow repair

Systems can change your status in real time, but repair happens on human time, slowly, optionally, and mostly by making you do labor.1

Healthcare makes it easiest to prove, because the impact of delay isn’t just annoying—it can be biological:

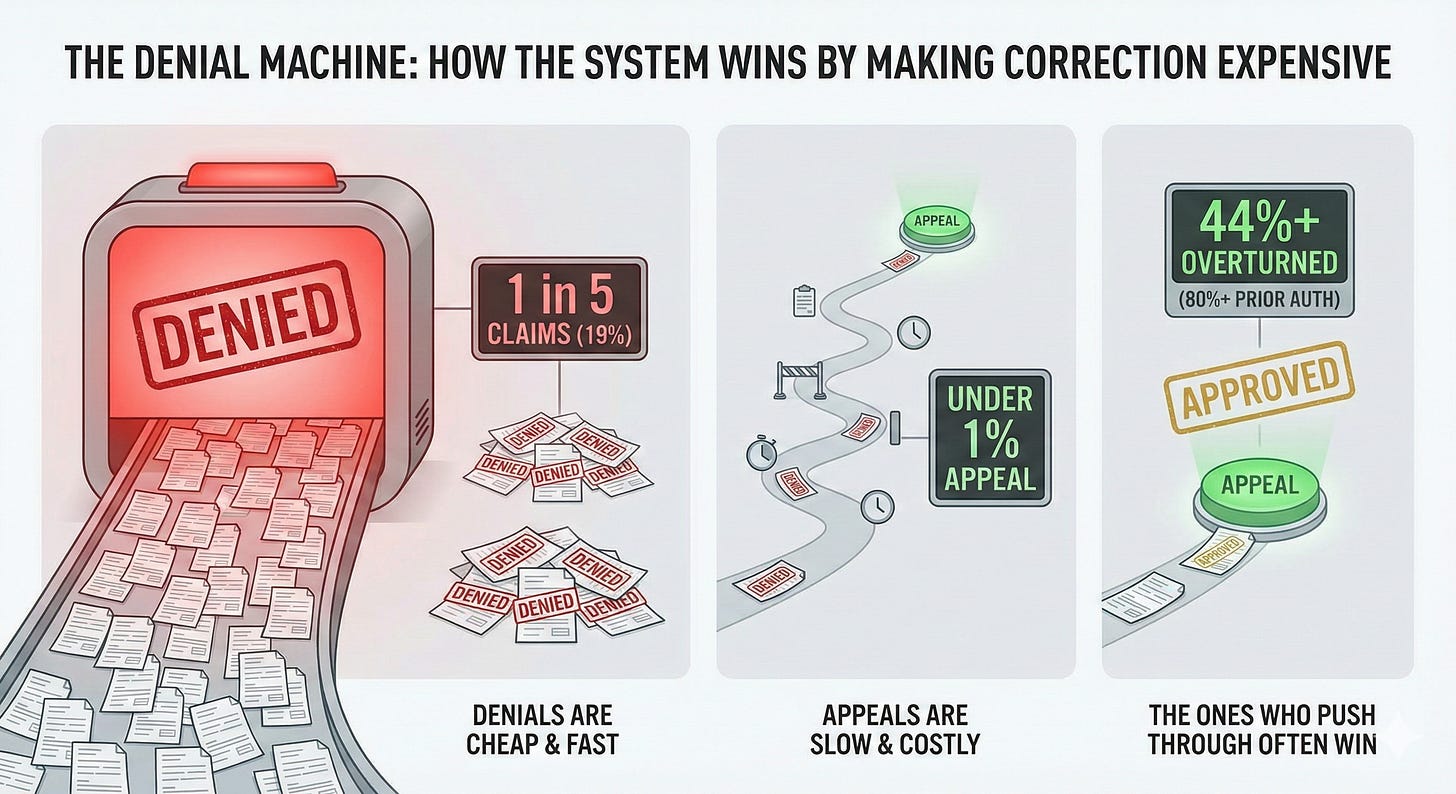

Denials are common. In 2023, ACA marketplace insurers denied about 19% of in-network claims (roughly 1 in 5).

Appeals are rare. Across tens of millions of denials, consumers appeal at under 1%.

Appeals work. When people do appeal, denials are overturned at least partially 44% of the time—and prior auth appeals succeed in some studies 80%+ of the time.

Almost nobody appeals. When they do, they often win. Stop and think about what that means: The system can afford to be wrong 19% of the time because it knows 99% of people won’t fight back.

Which means the system doesn’t win by being right. It wins by making correction expensive enough that most people can’t afford to try.

Denials are cheap and fast. Appeals are slow and costly—in time, energy, uncertainty, and risk.

But in the Age of Appeals, the ones who push through often win.

This isn’t just “a healthcare problem.” It’s a design pattern across high-speed, high-stakes systems.

I see the same structure everywhere:

Benefits: payments stop overnight; hearing dates land months later. Pennsylvania unemployment appeals can run 2–6 months. You still need rent and groceries during “the process.”

Housing: the move from filing to removal can be weeks. Illinois eviction cases can reach hearing in 7 days. Appeals exist, but they often don’t automatically pause harm —so “you can appeal” becomes technically true while you’re already displaced.

Platforms: a flag can erase an account and income instantly; “review” has no binding timeline and can stretch to “weeks or months”. The platform decides if you get your life back—and when.

Immigration: removal and detention can move quickly while the system that hears contests is backlogged for years. The right to contest exists inside a machine designed to outpace it. As I explored in Pending: The Politics of Non-Decision, indefinite waiting becomes its own form of control.

The new class divide is ‘error survivability’

Here’s what that implies, and it’s uglier than it sounds:

In a high-speed administrative world, class is increasingly measured in error survivability: who can absorb or reverse a wrong decision before their life comes apart.

Who can afford to:

Sit on hold for two hours on a Tuesday without getting fired

Write in institutional jargon without melting down

Front money while “it gets sorted out”

Keep backup accounts, backup housing, backup childcare

Pull in a lawyer, union rep, or journalist who gets a response

Remain functional while their status is “pending”

So the real Wealth is Error Insurance.

The most important Education is Procedural Literacy.

The key determinant of Health is Capacity to Endure Bureaucracy.

The same formal right behaves like a safety net for some and a dare for others.2

Why the usual fixes miss

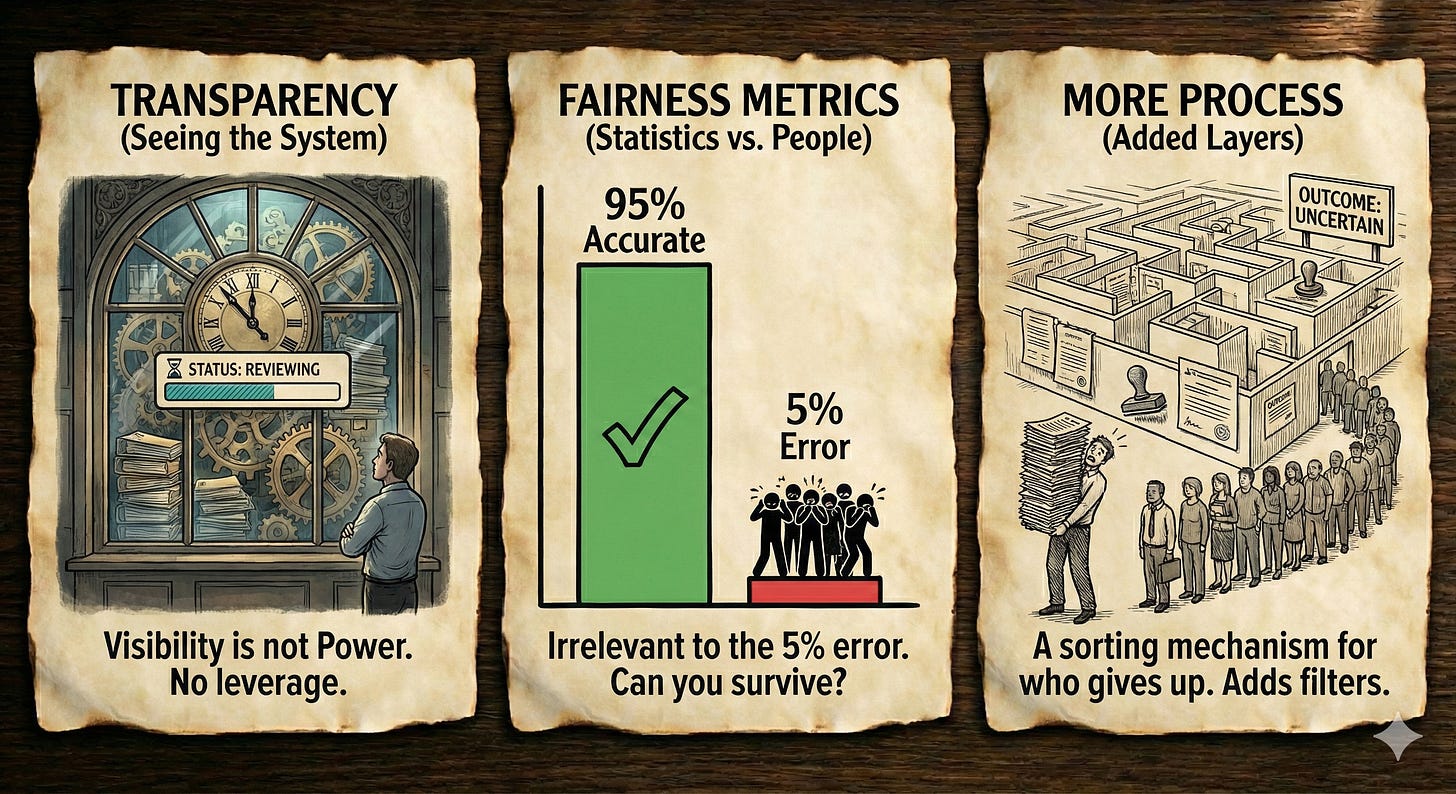

Transparency: You can see the policy, understand the reason code, watch the status bar—and still have no leverage. Visibility is not power.

Fairness metrics: A system can be “95% accurate” and still concentrate its errors on the people least able to contest them. For the person in the 5%, the metric is irrelevant. The question is: can you survive the mistake?

More process: extra forms and extra layers usually just add more filters for time, literacy, stamina. If process isn’t coupled to binding timelines and real outcomes, it’s just a sorting mechanism for who gives up.

All of these change how systems talk about themselves without changing what they can be forced to do.

What would actually work?

☐ Automatic stays for survival stakes

If an appeal is active, harm should not proceed for money-for-food, housing, essential medical care, or physical presence in a country. Default to continuity until someone with real authority resolves it.

☐ Binding deadlines with teeth

Pick numbers (14 days, 30 days). Enforce them. Missing the deadline shouldn’t be a “service failure”—it should trigger reversal or meaningful penalty.

☐ Burden on the actor

If a system flips your status, it should carry the burden of proving it was right—rather than forcing you to prove it was wrong while you’re under duress.

☐ Proportional capacity

If you can act on 100,000 people/day, you must be able to process 100,000 appeals/day within guaranteed timelines. Otherwise “you can appeal” is brochure text.3

☐ Cost-shifting when wrong

When the institution is wrong, it should pay the person’s costs (fees, lost wages where applicable, and recognition of harm caused by delay). Right now almost all costs sit on the individual.

None of this requires us to believe institutions are ‘evil.’

It just means we have to refuse to let them be careless for free.

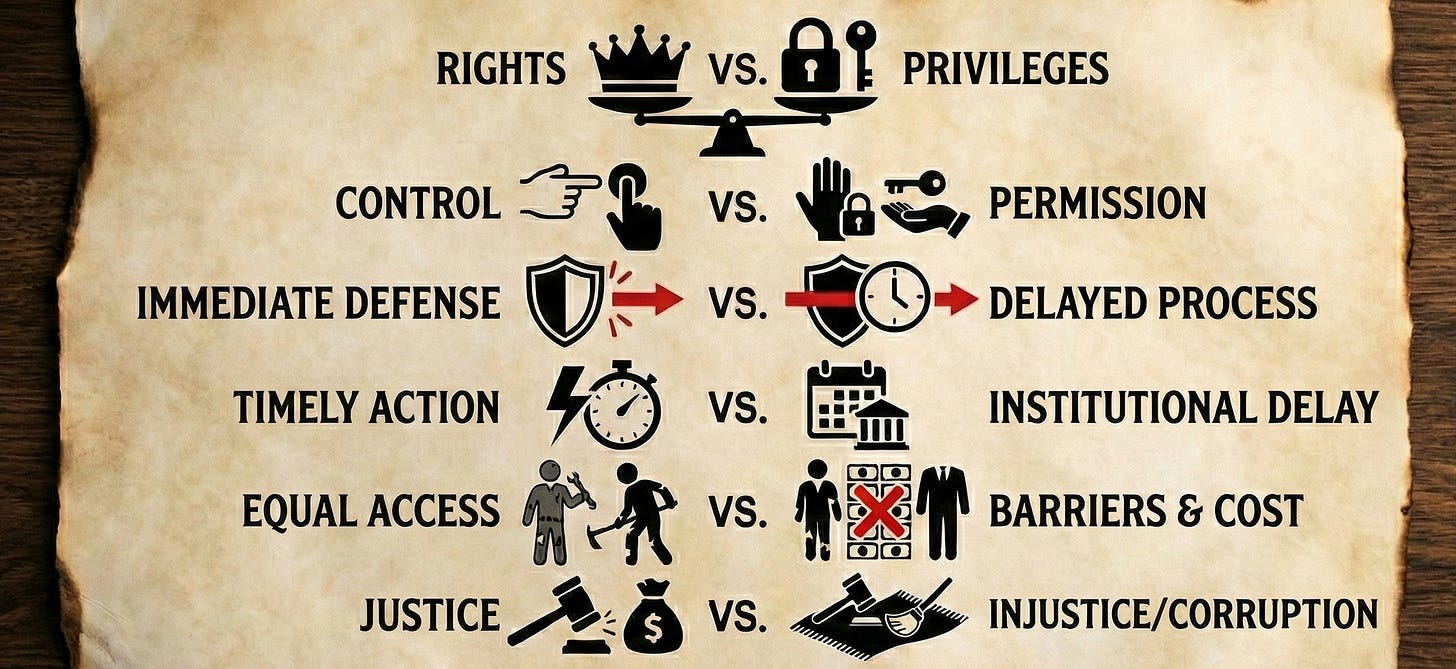

What rights actually are

A right isn’t a sentence on paper. A right is the machinery that moves when the sentence is violated.

I explored this more fully in On “Having a Right” to Something.

Can you trigger it yourself, or do you need permission?

Does it stop harm while it runs, or does harm continue during review?

Is it timed to your crisis, or institutional convenience?

Does it work when you’re broke, sick, exhausted, scared—or only when you’re composed and resourced?

Does it make the institution pay when wrong, or just quietly walk it back?

If the answers are mostly “no,” then you don’t have a right.

You have a story about a right—plus a test of whether you can survive the cost of making it real.

The constitutional crisis nobody noticed

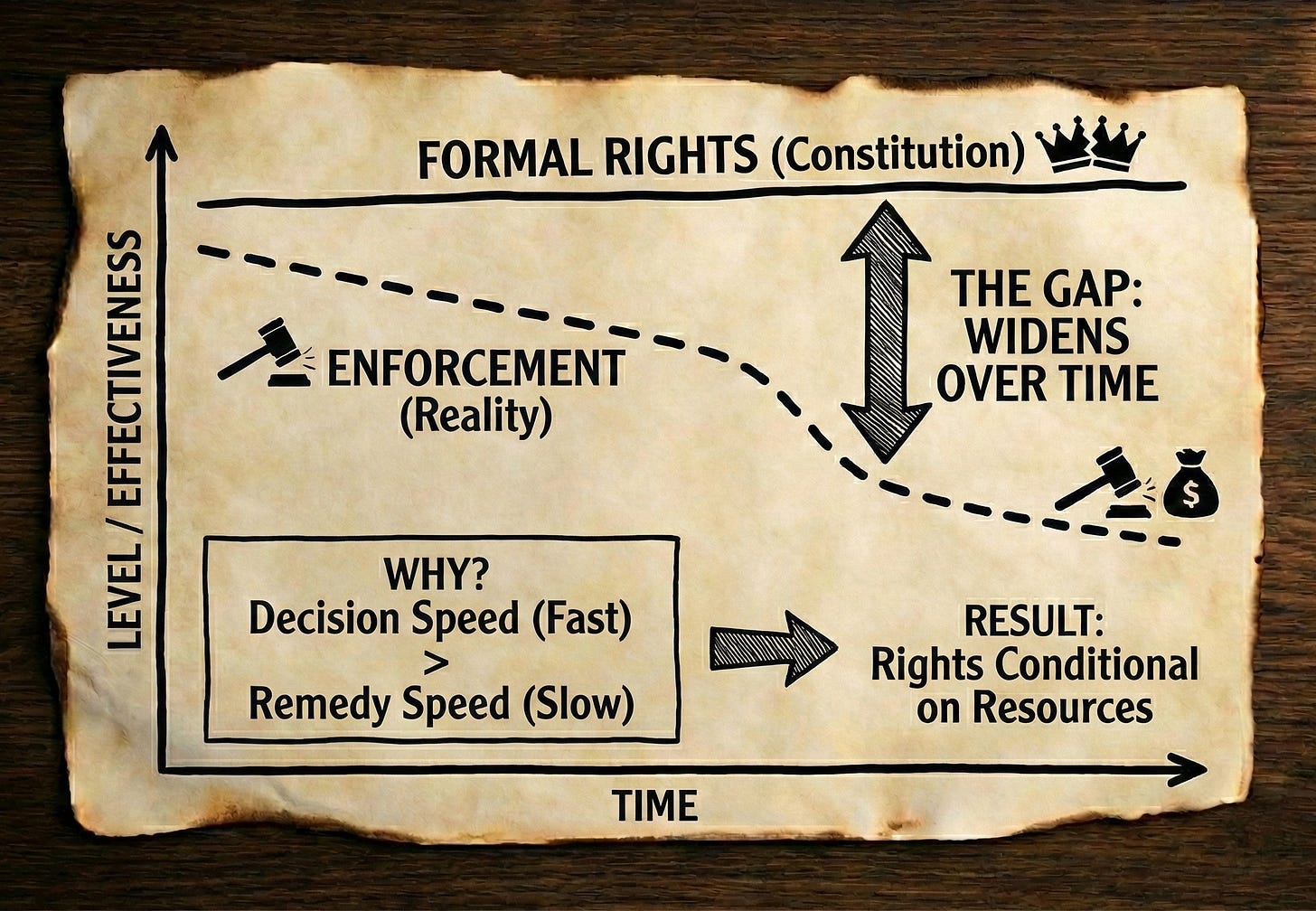

We’re living through the age where having rights and being able to enforce them have completely diverged—and most political discourse hasn’t noticed.

The formal constitution says one thing: you have rights, due process, equal protection. The operational constitution—what institutions can actually be forced to do—is something entirely different.

The gap is widening as decision speed increases while remedy speed stays constant. This creates a new form of domination: not through explicit denial of rights, but through making rights practically conditional on resources while maintaining formal universality.

Under high-speed, high-scale systems, the most important political question is no longer just “who decides?” or “what do the rules say?”

It’s: when the system gets it wrong, who can force reversal, how fast, and at what cost to whom?

Everything we currently call “rights,” “fairness,” or “accountability” will either be rebuilt around that question—or go on existing mostly as pamphlet language.

Until that question sits at the center of how we talk about healthcare, housing, welfare, platforms, policing, immigration—and everything else—we’re just arguing about whose turn it is to get the pamphlet.

If you’ve lived the gap between having a formal right and being able to enforce it—or if you’re building systems trying to close that gap—I want to hear about it.

This is part of ongoing work on what governance actually requires under conditions of high-speed, high-scale automated decision-making.

That asymmetry is, increasingly, the “governance model.”

I’ve written before about how this functions as governance by exhaustion—systems designed to make you quit rather than to get things right.

This isn’t just about having standing in the legal sense—it’s about having the capacity to make that standing matter. I wrote about this distinction in Belief is Not the Bottleneck. Standing is.

The healthcare numbers are the cleanest proof: when success rates are high but attempt rates are tiny, the bottleneck is not correctness—it’s capacity.