We're On It! The Age of Abundant Acknowledgement

Why being in process so often leads nowhere: Legitimacy engineering and “care signals” as governance tech

You fill out the form. A confirmation screen appears. A case number is generated. An email arrives—polite, calm, strangely reassuring: We’ve received your request. We take this seriously. Someone will follow up.

For a moment, something loosens in your chest. There is a record. There is proof you entered the channel. Whatever is happening to you—medical, financial, bureaucratic, interpersonal—has crossed a threshold from private trouble into recognized process.

Then the waiting begins.

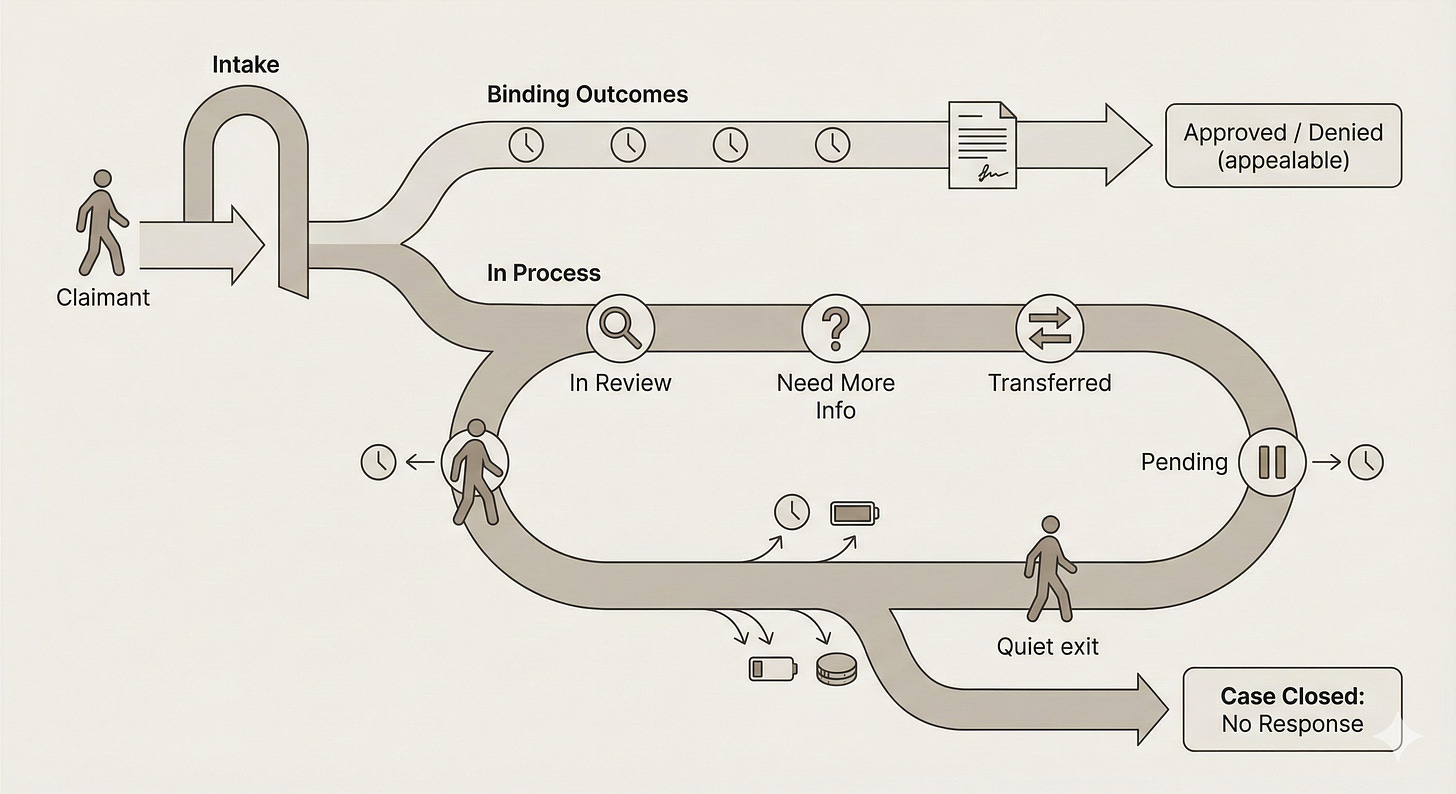

The status changes just enough to keep you from concluding that nothing is happening. In review. Pending verification. Assigned to the appropriate team. You may get requests for more documentation—the same PDF again, a clearer copy, a different format, a resubmission because the first upload “didn’t go through.” Each loop arrives wrapped in courtesy.

And still: nothing becomes a decision.

This isn’t a story about a few cruel people. It’s a story about a common design: systems that are very good at producing signals of care, and very reluctant to produce outcomes that bind them.

Signals are cheap. Outcomes are costly.

Most institutions can generate the reassuring parts at near-zero cost:

acknowledgments

apologies

status updates

“we take this seriously”

new ticket numbers

new portals

new “listening sessions”

Those signals aren’t fake. They matter psychologically. They reduce panic. They create the feeling that the situation has been admitted into a legitimate channel.

But the expensive part is different.

A real outcome costs something. It can set precedent. It can create legal exposure. It can force the organization to admit error in a way that travels. It can produce a written decision that can be appealed, audited, or compared to other cases.

So the system does what systems do: it produces the cheap thing abundantly, and rations the expensive thing.

That gap—cheap legitimacy, costly remedy—is where modern cruelty can live without anyone raising their voice.

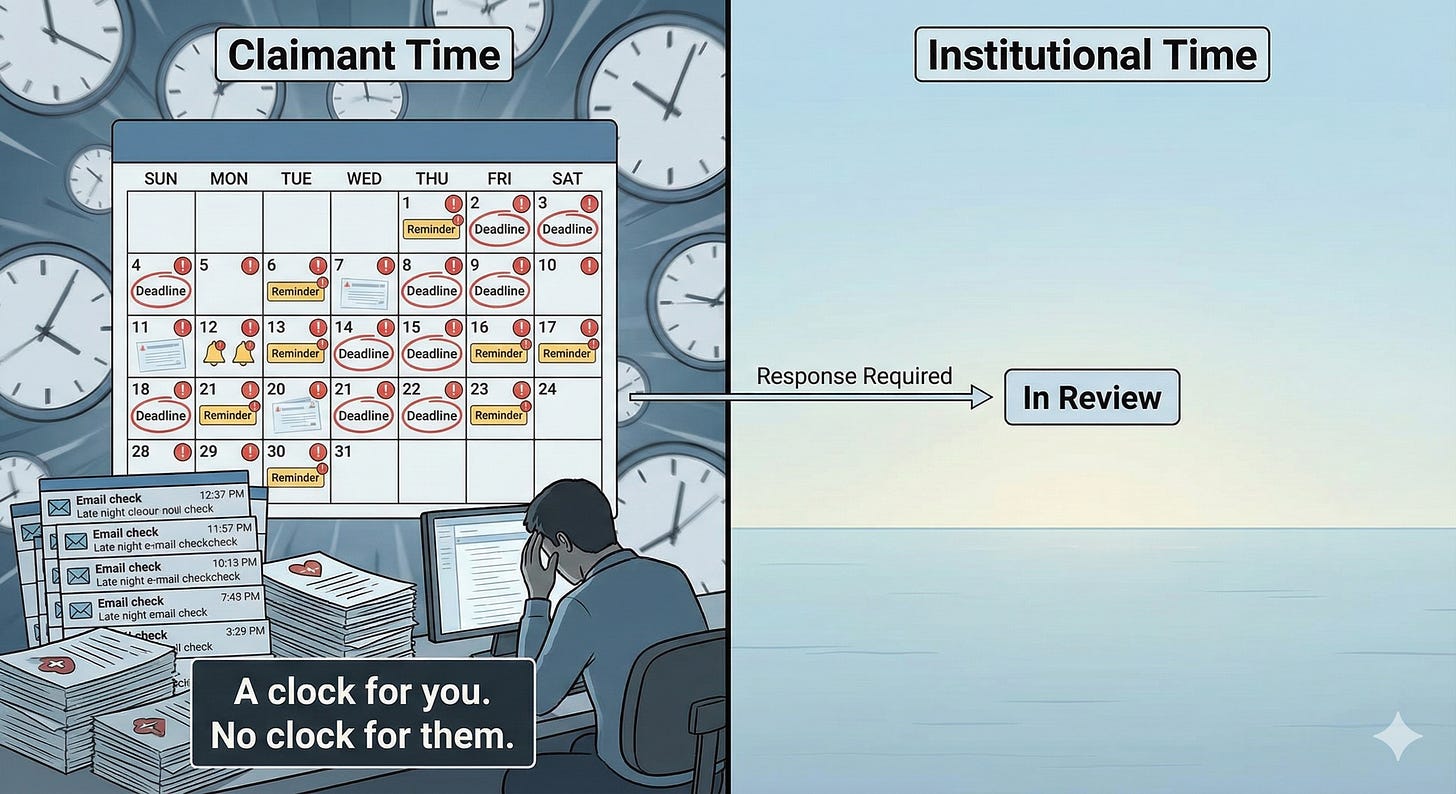

Time binds you. Time does not bind them.

These processes typically have a clock for the claimant: respond in 48 hours, submit within 10 days, attend the appointment, upload by Friday.

But there is often no enforceable clock on the institution’s side. You can be told to wait without a deadline. You can be told it’s “in progress” with no point at which “in progress” becomes “overdue.”

That asymmetry does something strange: it lets your situation get worse while the system remains calm. Harm can intensify without triggering any obligation to act.

Your urgency exists in your life. The process remains serene.

Many systems don’t need a decision to function.

In the civics story we tell ourselves, conflict produces a decision: approval, denial, a reason-in-writing, something you can contest.

In a lot of modern systems, that isn’t required.

Delay can restrict you. Non-response can effectively deny you. You can lose access while the system never produces a written, appealable conclusion. Nothing solid is created—no “object” you can point to and say: this is what happened and this is what I’m contesting.

The power move is not always to deny. It’s to never finalize.

“Escalation” is often just movement, not change.

Most systems advertise escalation: talk to a supervisor, file an appeal, request review.

Here’s the test that matters:

Does escalation change who can decide?

Does it add a deadline the institution must meet?

Does it force a written outcome?

If not, escalation is mostly a coping feature. You get a new person, a new inbox, a new tone. The underlying authority stays the same. The system remains free to not decide.

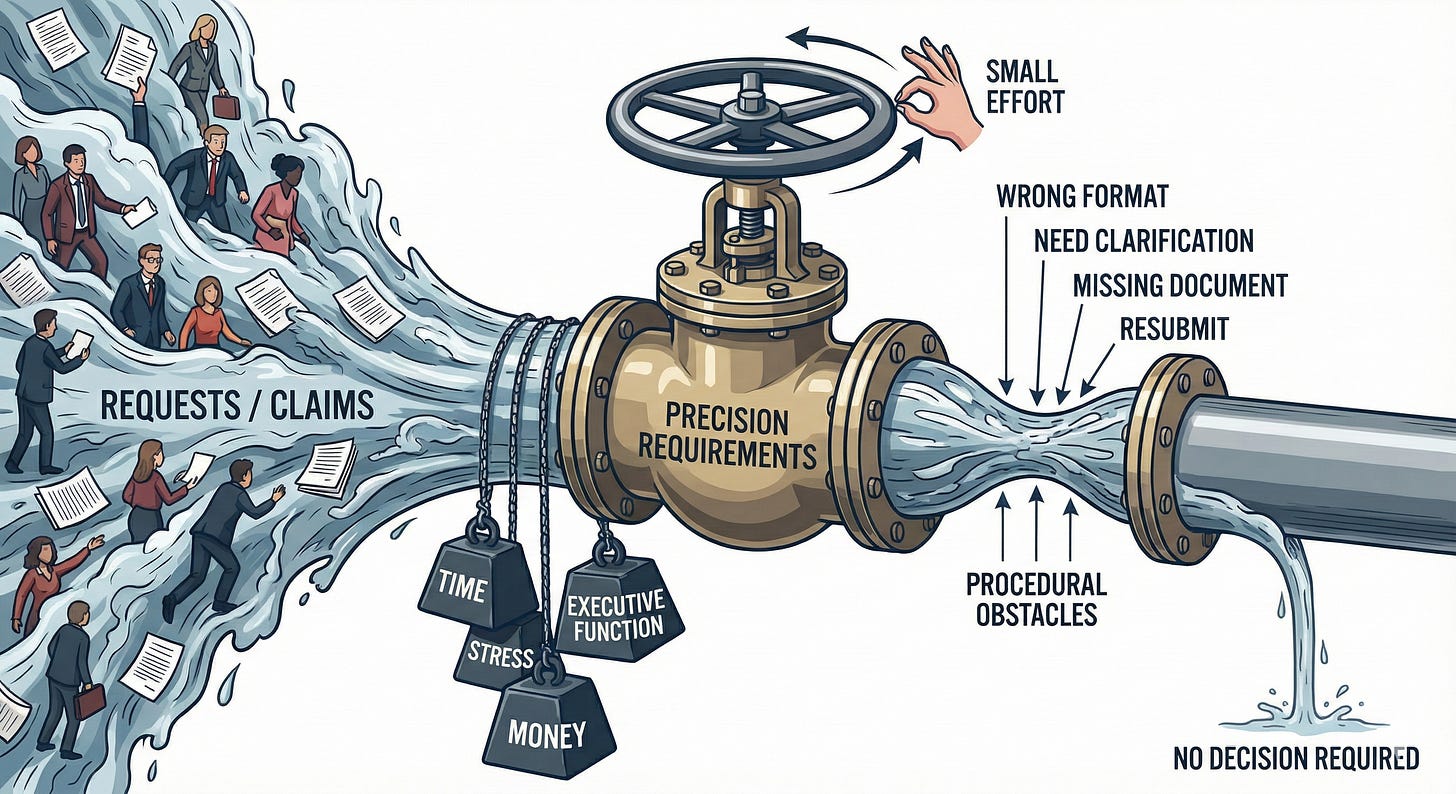

Precision becomes a burden, not a virtue.

Another common pattern: the system can always ask for more specificity.

It’s cheap to request: “please clarify,” “provide more documentation,” “submit in a different format.”

It’s expensive to satisfy: time, executive function, money, coordination, emotional labor.

That creates endless failure points: one missing detail, one wrong file type, one missed call, one forgotten step. And when you stumble—predictably, under stress—the stumble is treated as your moral failure.

The system makes “keeping up” expensive and then calls the cost “responsibility.”

Dropout isn’t just what happens. It’s what the system uses.

Eventually, many people stop.

Not because they were satisfied. Because they’re exhausted. Because they’re sick. Because they have to work. Because their phone number changes. Because they can’t keep reproducing the same proof for a process that never acknowledges it has already been provided.

And here’s the inversion: many systems can close the case without deciding anything. “No response.” “Inactive.” “Abandoned.” “No further action.”

Your stopping becomes the thing that lets the system file the episode away as resolved.

Dropout is converted into consent after the fact; it “guesses” you didn’t actually need the help.

This is why it’s not a decision system. It’s a selection system.

When signals are cheap and outcomes are costly; when time binds only one side; when cases can end without decisions; when escalation doesn’t change authority; when precision demands create repeated failure points; when dropout can be recorded as closure—

the process isn’t mainly deciding who is right.

It is selecting for who can stay in the process without breaking.

Outcomes aren’t allocated by need, correctness, or entitlement. They’re allocated by survivability under delay.

Participation doesn’t reliably increase the probability of remedy. It reliably increases the carrying costs borne by the claimant.

In short:

When those conditions hold, governance is exercised through the managed distribution of exhaustion.

The design question that follows is not “How do we make the process nicer?”

It’s: where does the system become obligated to deliver an outcome—and what happens when it doesn’t?

If the answer is “nothing,” then the system is governing by non-settlement. And changing it won’t come from tone. It will come from clocks, real escalation, written decisions, and consequences for indefinite delay—because that’s where the power actually lives.

Until those mechanics change, the most vital move is a cognitive one: refusing to mistake the signal for the outcome. The polite email is not progress; it is a notification of stasis. The request for clarification is not a dialogue; it is a throttle.

Seeing the design clearly won’t make the wait shorter. But it might stop you from internalizing the system’s friction as your own moral failure. When you know you are trapped in a machine designed to test your endurance, the hardest—and most necessary—thing to do is refuse to participate in your own exhaustion.