Stop Preaching. Start Engineering.

Goodness isn’t a moral trait; it’s a design property. When systems reward correction instead of denial, virtue becomes infrastructure.

We’ve all known someone like this: the dedicated manager in a toxic corporation, the compassionate teacher in a broken school system, the honest public servant navigating a bureaucracy of bad faith.

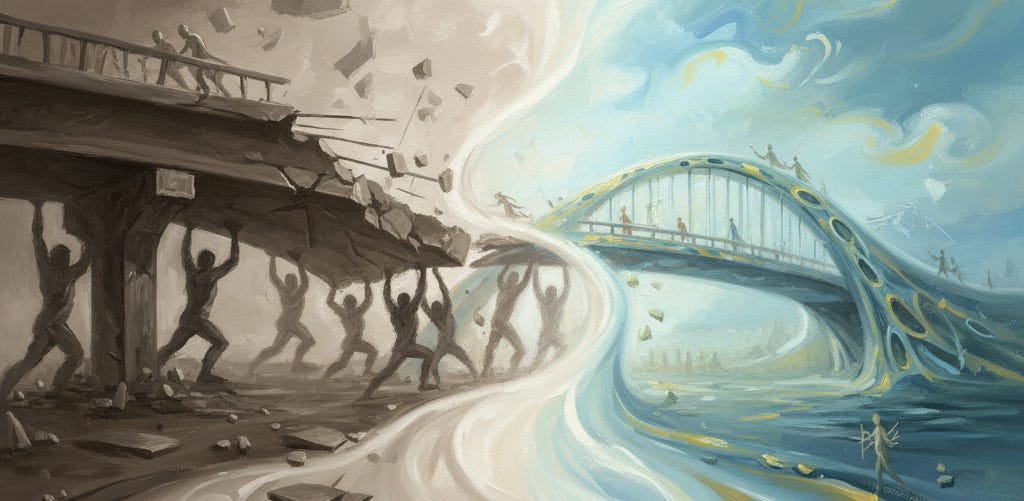

They work tirelessly to do the right thing, fighting against the very structure they inhabit. We call them heroes, celebrating their personal integrity. But as Why We Need Fewer Heroes argues, that celebration is itself a design flaw. Heroism is the evidence of a system that only survives by consuming its best people.

The moral problem of our time isn’t a lack of good individuals—it’s the presence of bad architectures. For centuries, we’ve measured goodness through character, intent, and sacrifice. But intent is no defense against structure.

As On Bad Terrain and Ethics Is What Gets You Fired both show, even the most conscientious actors reproduce harm when the environment rewards complicity and punishes repair.

From Moral Psychology to Moral Architecture

We need a new kind of ethics—less sermon, more schematic. Ethics not as purity of motive, but as design of feedback. Not moral instruction, but moral engineering.

In Critical Bioengineering, I wrote that the first question any responsible designer must ask is: when stress arrives, who carries it? That is the central question of system morality too. The same laws of stress and load that govern materials govern institutions. When a structure cannot absorb strain, it exports it—onto workers, citizens, and the planet. We mistake endurance for virtue, but as Survival Isn’t Proof of Worth notes, endurance without correction is just rot with good PR.

The most ethical system, then, is not the one that avoids failure, but the one that knows how to fail well. As The Right to Fuck Up argues, healthy systems expect error and metabolize it. Goodness is not perfection—it’s corrigibility.

The Four Pillars of Moral Infrastructure

So what does moral corrigibility look like in design? Humane systems can be recognized by the mechanisms that make goodness the path of least resistance. Their architecture rests on four feedback functions:

The Learning Mechanism (Humility) – A structure that can learn from stress rather than hide it. Built-in transparency, whistleblower protection, and independent audit make self-correction possible.

The Responsive Mechanism (Compassion) – A humane system acts first to mitigate harm before assigning blame. Compassion is operationalized as triage, not sentiment.

The Adaptive Mechanism (Flexibility) – As Sanctiphagy shows, rigid institutions devour their own saints. Adaptive systems instead adjust their parameters so that decency doesn’t require martyrdom.

The Truth-Verifying Mechanism (Honesty) – Systems that distribute the work of truth—through open-source verification, peer review, or civic oversight—convert honesty from a virtue into an emergent property of the network.

These pillars together form what earlier essays only gestured toward: a blueprint for moral infrastructure. Each transforms individual virtue into collective capacity.

The Measure of a Humane System

The old morality asked: Are you good? The new one must ask: Can this structure make goodness sustainable?

The true measure of a good society is not how many saints it produces, but how easy it makes it for ordinary people to be good.

Further Reading

Each of these pieces explores a facet of moral design — from how institutions absorb stress to how honesty can be built into systems rather than demanded from individuals.

Critical Bioengineering: When Institutions Break, Bodies Pay

On how stress physics applies to bureaucratic and digital systems — and why failure always finds a body to land in.Why We Need Fewer Heroes

Argues that heroism is evidence of structural failure, not moral excellence. A humane system shouldn’t require saints to survive.Sanctiphagy

Examines how institutions consume their most conscientious members and turn virtue into fuel — the moral economy of burnout.The Right to Fuck Up

On the necessity of corrigibility — why repair, not perfection, is the mark of moral architecture.Survival Isn’t Proof of Worth

Challenges the idea that endurance equals goodness; longevity without correction is just rot with good PR.