Survival Isn't Proof of Worth

On vicious longevity

From corporations and political parties to the algorithms that govern attention, we’ve mistaken survival for success. If something has lasted, we assume it must be doing something right.

But endurance often signals insulation rather than virtue. The longest-lived systems—oil companies, financial institutions, monopolistic tech platforms—survive not by merit but by making themselves irreplaceable. They’ve learned to turn harm into stability, converting damage into justification for their own existence.

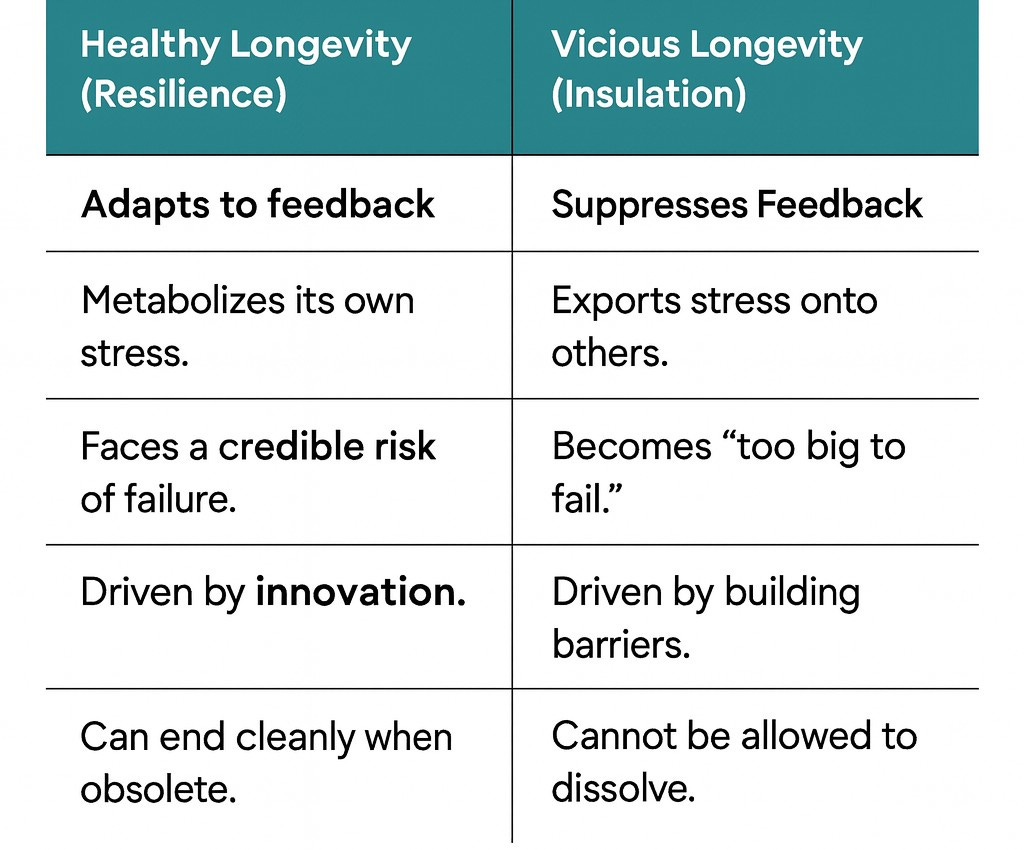

Survival is not a moral argument. It tells us only that something has found a way to persist, not what that persistence costs or who pays for it. A parasite survives by draining its host. A bureaucracy endures by making people replaceable. The most durable systems export their stress outward—onto workers, consumers, ecosystems, and future generations. Then they call this resilience.

We confuse continuity with health because stability looks calm on the surface. But systems that never face consequence become brittle over time.

Indeed, true resilience is characterized by the ability to recover, rather than the absence of setbacks. A system that cannot adapt without critical failure demonstrates a lack of inherent strength and, consequently, inflexibility.

Sometimes endurance is just rot with good PR.

Four Patterns of Vicious Longevity

1. Stagnation Over Innovation

Survival without competition breeds decay. When switching costs replace improvement, continuity becomes capture. The so-called Lindy effect mistakes age for virtue, assuming that whatever has endured must possess some inherent quality. This logic fails when entities survive by eliminating the very forces that would test their worth.

2. Institutions deemed “too big to fail” survive by offloading mistakes onto the public.

Stability gets purchased through externalized suffering. The 2008 financial crisis demonstrated this dynamic with brutal clarity: banks gambled recklessly, triggered global collapse, then survived through bailouts while millions lost homes and savings. Their longevity was purchased with public money and private anguish.

3. Unrepaired flaws compound over time into structural pathologies.

What began as a slight bias in hiring becomes, fifty years later, a deeply discriminatory organizational culture. What started as a minor legal loophole becomes, across decades, a highway for corruption. The entity survives, but transforms into something toxic.

4. Dominant systems maintain power not by being better but by preventing “better” from emerging.

Tech platforms acquire potential competitors before they pose real threats.

Established industries lobby for regulations favoring incumbents. Continuity metastasizes into monopoly.

As layers of dependence accumulate, replacing a failing system feels impossible. Every dependency adds weight: login credentials, legacy contracts, sunk-cost regulations. What we call stability is often just damage frozen in place. Continuity transforms into moral currency. The longer something survives, the more sacred it becomes, even when it has stopped serving anyone but itself.

This approach appears to foster an endurance economy, monetizing longevity and delaying collapse through extraction. Climate adaptation is then rebranded as “stability protection,” effectively translating a planetary emergency into fiscal terms. This, however, does not seem to be a genuine form of repair, but rather an accounting practice disguised as ethical behavior.

The real measure of a system is not how long it lasts but how well it learns.

Can it correct itself without coercion? Can it end cleanly when its purpose expires? A just institution earns the right to endure only if it metabolizes its own stress and remains accountable to those it affects.

If harm is the maintenance cost, stability is just deferred collapse.

The systems worth keeping are those that can heal, adapt, and—when the time comes—end with honesty.

Sometimes endurance is just rot with good public relations. Longevity should never be proof of worth. Instead, it should beg the question of what the world has had to pay for it.