Toothless Ethics: Why Principles Don’t Stop Machines

A guide to the difference between moral language and structural constraint

Modern institutions have become remarkably good at discussing ethics.

They publish principles, run trainings, hire “responsible” teams, and build high-fidelity dashboards to track harm. The language is polished, the intentions are often real, and the concern sounds sincere.

And yet the behavior rarely changes.

The issue isn’t always hypocrisy. In many organizations, “ethics” functions as a way to metabolize discomfort without altering the machine’s trajectory. Anxiety is converted into documentation, meetings, and process—so the system can keep moving at the same speed, in the same direction.1

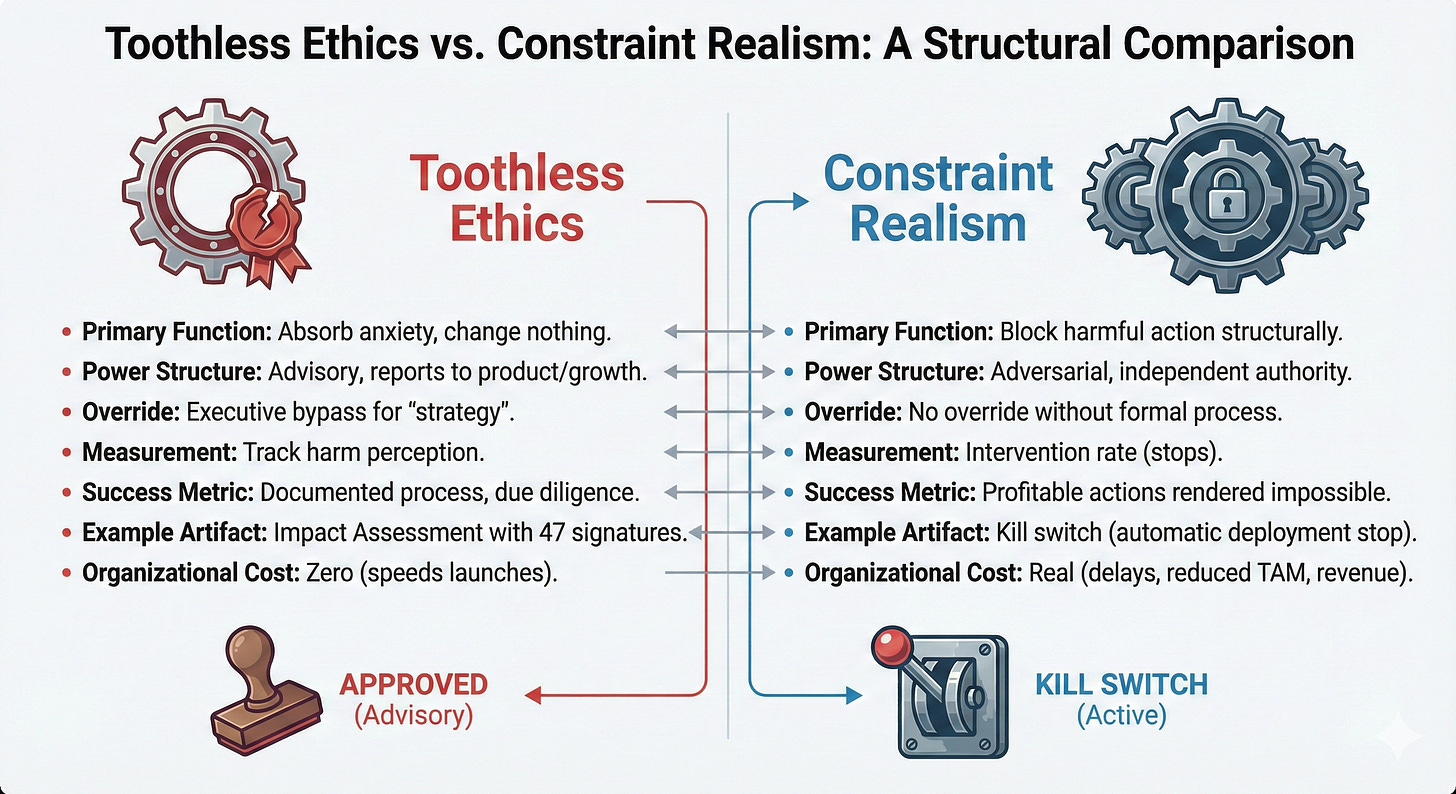

This is Toothless Ethics: oversight that performs the rituals of responsibility without the power to force a sacrifice.

The Dashboard Trap

We often assume that if leaders could see harm clearly, they would stop it. So we build observability. We measure “toxic content,” “provider burnout,” and “bias incidents.”

But large systems do not reliably respond to visibility with correction. They often respond with management.

Once harm becomes a metric—numbers on a dashboard, incidents in a report—it can be treated not as a violation, but as an operational variable: How much can we absorb without consequences? Where is the line where it becomes expensive?

In that world, awareness doesn’t destabilize the machine. It stabilizes it. It teaches the organization exactly what it can get away with. As I argued in Assume Maximum Awareness, organizations that track harm with high fidelity often do so not to prevent it, but to price it—learning precisely how much damage they can absorb before consequences arrive.

The “Homemade Key”

You can often identify a toothless system by an architectural flaw: the coexistence of a primary safety protocol and a secondary, informal bypass.

In December 2023, inspectors at an Australian manufacturing facility found that safety interlocks on a CNC machine had been overridden with a homemade metal key. A worker had become trapped in the machine and suffered broken ribs. The safety system existed technically; the bypass existed practically, preserving throughput.2

The chilling part isn’t the key. It’s the logic. The key was homemade because the demand was structural. Someone built that key not to be malicious, but to keep the line moving.

In corporate governance, the “metal key” is the executive override.

If a safety rule can be bypassed via a private message to a founder, or a “special exception” for a major client during a deadline crunch, then the rule is not a constraint. It is etiquette.

At the interface level, this appears as design patterns that make refusal expensive—the digital equivalent of the homemade key, where saying “no” requires navigating deliberate friction while saying “yes” is one click away.

The Solution: Constraint Realism

We need to stop treating ethics as a culture problem—a matter of values and intent—and start treating it as a design problem.

I call this doctrine Constraint Realism.

It treats ethics as real only when it exists as a hard constraint on what actions remain available. Ethics is not defined by what a system claims to value, but by the profitable actions it has rendered impossible.

To evaluate whether an institution’s ethics are binding, do not look at its mission statement. Look for the Foregone Advantage:

Show me what you can no longer do.

Show me the launch you canceled despite the revenue projection.

Show me the “report” button that reverses a database state, rather than merely filing a ticket.

Show me the remediation gate leadership couldn’t unlock.

If an organization cannot point to specific advantages it sacrificed because a constraint held, then its ethics are decorative: reputation management with better vocabulary.

The Care Subsidy

Systems without binding constraints often appear stable only because they rely on human compensatory labor to prevent failure.

I call this the Care Subsidy: the extraction of unpaid diligence from conscientious employees to bridge the gap between resource allocation and safety requirements. You see it in the nurse who stays late to secure a bed, or the moderator who absorbs psychological injury to clear a queue.

As I argued in You are the Crumple Zone Now, a system that depends on heroism to function safely is under-designed. It relies on exhausting its components to maintain integrity.

When that human infrastructure inevitably fails, institutions often reframe the structural deficit as individual noncompliance. Blame serves a functional purpose: it protects the design by locating failure in the person, ensuring that re-engineering is avoided.3

The Politics of “No”

Ultimately, this is a question of power: consent is not valid if refusal is not safe.

If opposing a dangerous course of action produces professional retaliation, then compliance is coerced. In such an environment, ethical discourse is delegitimized—not because the words are insincere, but because dissent carries a prohibitive cost.

We have to stop preaching and start engineering. We need organizations where “no” is a normal operational outcome, not a career-ending event.

And yes: that creates friction. It costs time, money, and flexibility. That isn’t a failure of ethics—it is the proof that ethics is real.

Because if your ethics never blocks a profitable action, never slows you down, and never forces you to accept a loss, then it isn’t binding.

It’s just a story the machine tells while it keeps running.

Stop asking for "better values" from leadership and start demanding structural veto power over deployment.

Related Essays:

Assume Maximum Awareness — Why organizations measure harm to price it, not prevent it

You are the Crumple Zone Now — On care subsidy and human infrastructure

[Accept All] / [Reject All] — Interface-level constraint design

Stricter in Love Than in Law — The Black-Box Alibi and accountability theater

I contend that any ethics framework that is voluntary is functionally essentially a marketing expense. In a competitive market, a company that voluntarily accepts a "Constraint Discount" (sacrificing revenue for safety) will be out-competed by one that doesn't—unless the constraint is universal.

https://safework.sa.gov.au/news-and-alerts/safety-alerts/incident-alerts/2023/dangers-of-bypassing-safety-devices

Much of the current debate about "AI Safety" focuses on technical alignment—how to mathematically ensure an AI does what we want. I counter that technical alignment is irrelevant without political alignment. You can build a perfect safety tool, but if the "growth team" has a bypass key (like Uber's Greyball or the CNC machine), the tool will be ignored.