You Can Design Harm Out

How to design systems that protect human limits and reject harm as the path of least resistance

Most systems cause harm not through intentional malice but because their architectures inherently make harm the cheapest option for maintaining stability.1 Institutions typically rely on constant compliance, output, and human endurance (or buffer capacity). When these demands exceed human limits, harm is offloaded onto vulnerable groups—workers, moderators, communities, or users, reflecting systemic brittleness rather than accidents. This brittleness, as Nancy Leveson’s systems safety research shows, arises from complex, interacting components and institutional incentives that prioritize extraction over human-centered outcomes.2

Humane systems are those that do not assume infinite or flawless human capacity, do not offload harm to hidden labor or the environment, and do not collapse when humans refuse or fail.

This is why institutions don’t really become humane by wanting to. Their incentives tilt toward extraction and their defaults drift toward brittleness. Humaneness isn’t a virtue they can adopt; it’s a structure they would have to rebuild.

Designers, however, can do something institutions can’t: encode restraint into the artifact itself. Build systems that don’t need heroism. Interfaces that refuse to punish confusion. Infrastructures that remain stable when someone says no.

You don’t need an ethical revolution to prevent harm. You need architecture that refuses to use people as the shock absorbers.

Some artifacts already show how design makes room for human limits. Emergency stop buttons let anyone hit pause—no questions asked. GFCI outlets expect mistakes and cut power before things get dangerous. These features don’t ask for perfect users. They just keep people safe.

Other designs do the same for bigger problems.

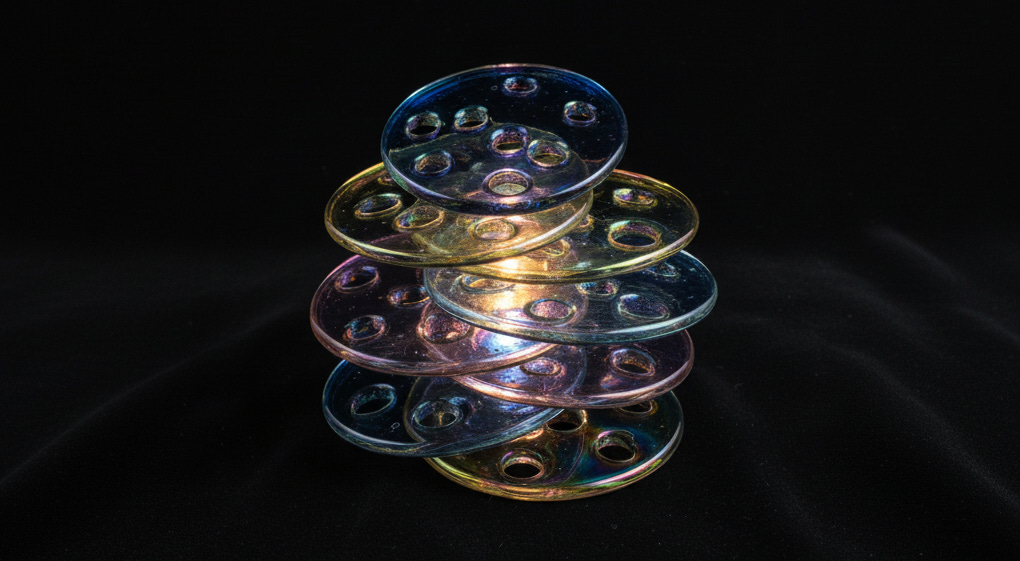

Modular hardware lets you fix devices instead of tossing them out, so the cost doesn’t get passed on to workers or the environment.

Distributed version control means if one person slips up or drops out, the whole system doesn’t crash.

None of these rely on people being heroes; their fairness and safety are built into the design itself.

The same logic can be extended into systems we haven’t built yet.

A consent layer where permissions decay unless renewed.

A transactional buffer that makes irreversible financial actions reversible for 72 hours.

A “meltdown mode” in interfaces that detects panic taps and enlarges safe options.

A coordination tool that negotiates constraints automatically instead of relying on an overworked team member to be the emotional fulcrum.

The pattern is simple: harm emerges when a system relies on human exceptionalism. When it presumes constant vigilance, perfect memory, flawless timing, infinite patience—when it treats people as though they are the most reliable component in the loop. Leveson’s system models show the opposite is true: people are the variable element, and systems must be designed to expect that variability rather than punish it.

To design harm out is to design systems that expect people to be finite, unevenly resourced, distractible, grieving, overwhelmed, brilliant, autistic, disabled, aging—real.

As Mia Mingus shows in her work on access intimacy, most systems are designed around hypothetical users living hypothetical days. Sara Hendren’s work demonstrates that good design begins from the truth of human bodies, not the fiction of idealized operators. Humane systems remain stable, not just for ideal users but across the full range of actual human states.

This shift reframes the ethics of refusal. Systems become humane…

When they treat “no” as normal.

When they provide access without loyalty tests.

When they degrade gracefully when someone disappears.

When they carry their own externalities instead of distributing them to invisible classes of laborers or future generations.

When they do not collapse the moment a single exhausted human stops holding everything together.

Humaneness is not some warm, fuzzy feeling you can tack on at the end. It is not a corporate value a company can declare. It is an engineering constraint—like voltage limits or latency budgets—that determines what the system can and cannot do to the people who rely on it.

Harm reduction is fundamentally an engineering problem before it is an ethical one. So yes, you can design harm out, but only if you begin by refusing the illusion that people are load-bearing, infinite, replaceable components.

References:

Langdon Winner, “Do Artifacts Have Politics?” Daedalus 109, no. 1 (1980).

Nancy Leveson, Engineering a Safer World: Systems Thinking Applied to Safety, MIT Press, 2012.

Kat Holmes, Mismatch: How Inclusion Shapes Design, MIT Press, 2018.

Sara Hendren, What Can a Body Do? How We Meet the Built World, Riverhead Books, 2020.

Mia Mingus, “Access Intimacy: The Missing Link,” Leaving Evidence, https://leavingevidence.wordpress.com/2011/05/05/access-intimacy-the-missing-link/.

“...the design or arrangement of some artifact or system becomes a way of settling an issue in the affairs of a particular community. It becomes part of how decisions are made and enforced, not by deliberate policy, but because the artifact or system itself makes certain things easy or difficult, possible or impossible.”

-Langdon Winner, Do Artifacts Have Politics?

“We are starting to see an increase in system accidents that result from dysfunctional interactions among components, not from individual component failure. Each of the components may actually have operated according to its specification (as is true for most accidents), but accidents nevertheless occur because the interactions among the components cannot be planned, understood, anticipated, or guarded against.”

— Nancy Leveson, A Paradigm Change for System Safety Engineering (And Security) [Youtube Link]