Are You Usable Again Yet? (Clearance Culture)

In our burnout culture, "clearance culture" turns care into compliance. When are you truly ready to return to work? This essay unpacks the ethics of healing on a deadline.

There’s this thing that happens when “okay” stops meaning “I feel alright” and starts meaning “you’re cleared.” Suddenly, care starts sounding like compliance, and rest becomes a form of processing.

This is how modern power works: not by denying rest, but by scheduling it. Not by forbidding care, but by timing it. Recovery becomes paperwork.

“Rate your mood.” “Describe your progress.” “Ready to return?”

Every system that touches recovery asks the same implicit question: are you usable again yet?

It arrives as empathy formatted for a deadline. You’re asked to describe your suffering in administrative time. “Okay” no longer means whole; it means predictable, punctual, back in rhythm.

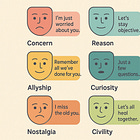

This is the logic of clearance culture, the system that treats recovery as a throughput problem. It wears the language of care while managing the logistics of extraction.1 “Are you okay?” sounds humane but functions as a scheduling query, demanding an answer that can be entered in a cell. Whether or not anyone intends harm is irrelevant; the cruelty is in the calibration. Empathy becomes a management interface, a lubricant for compliance.

How Time Shapes Our Expectations

This shows up in how we think about time, too. Sick days get a countdown. Grief gets a time limit. Wellness apps show how many days you’ve “recovered.” The calendar starts to shape our sense of what’s right. If you bounce back quickly, people admire your grit. If you need more time, you seem weak or unreliable.

The real power now is in the timing. Rest is allowed, but only on the system’s schedule. You get constant reminders, gentle nudges to get back to normal as soon as you can.

The Unequal Pressure to Pretend

There’s also this deeper problem: not everyone has the same freedom to take the time they need. People with job protection or resources can recover at their own pace.

Others have to pretend they’re fine even when they’re not. You send that “I’m fine” email from the car, or go back to work before you’re ready, just to stay afloat.2 In these situations, being “okay” really means you’re still marketable.

Admitting you’re not okay is risky.

Small Acts That Reveal Bigger Flaws

Despite all these structures, the system survives on small acts of bending the rules. It’s the nurse who lets someone stay longer, the teacher who quietly extends a deadline, the manager who swaps a shift to give someone a break. These little acts are often called “kindness,” but they also show the system isn’t actually working for people. If care only happens when someone breaks the rules, the rules are the real problem.

And “resilience” sounds good because it credits both the person and the system. The individual gets praised for enduring tough conditions, while the system keeps things moving as usual. But real change doesn’t happen if we only focus on making people tougher instead of fixing what wears them down in the first place.

Steps Toward Fairer Systems

So how do we make it better? First, we have to be honest that clearance and care are not the same.

Clearance is about ticking boxes and returning to output.

Care is about helping people when they’re not able to contribute at all.

A fairer system would center the individual in deciding what “ready” means: you, with input from your doctors and support network, not dictated by workplace demands. The organization would build in flexibility as a baseline, so one person’s absence doesn’t create chaos—meaning the burden of proof shifts to the system, not the employee. Policies would accommodate the unpredictability of healing, like extended leave without penalties or phased returns on your terms. We should only collect information that truly protects people, and conduct regular equity audits to ensure no one is rushed or overlooked based on their background.

None of this is just about personal kindness—it’s about redistributing power over time and restructuring systems to prioritize human needs.

Redefining Care in Society

Change is also about more than just updating a few rules. A care-centered society would prepare for times when people need more help than expected. It would budget for slow healing, for grief that returns, for days when rest just isn’t enough. We should be measured not by how fast people get back to work, but by how safe it is for them to pause.

Healing takes whatever time it takes. Real care doesn’t force you to return before you’re ready. It stays with you, no matter how long you need.

Some of my favorite recent writing on this c/o Beatrice Adler-Bolton:

Technology isn’t much help here. They teach users to pre-clear themselves—to ask not “How do I feel?” but “Am I trending acceptable?” You find yourself paying attention to charts and dashboards, not to your actual feelings or needs.