Governance by Caricature

Modern systems are designed around a particular kind of person. Not a statistical average or a real human being, but a convenient fiction: a user whose life aligns cleanly with the assumptions embedded in workflows. This figure rarely appears in writing, yet their outline determines everything—how quickly responses are expected, how rigid a deadline can be, and how many steps must be completed without interruption.

This is the “reasonable person” as imagined by modern infrastructures. A person with stable income, predictable availability, continuous attention, consistent documentation, and enough slack in their life to stay perfectly in sync with whatever the system requires.

The problem is not that such a person doesn’t exist. The problem is that most actual human lives don’t—and can’t—conform to this model. When they don’t, the people living those lives are quietly recoded as the problem: the unreasonable people the system cannot accommodate.

I. The Myth of the Ideal User

Every system simplifies in order to function. But as institutions become more automated and optimized, their user-models narrow. Simplification hardens into requirement.

A “reasonable” user becomes someone who:

can respond within the specified window

can complete tasks in one sitting

can navigate updated systems without losing their place

can gather documents immediately

can schedule around limited service hours

can absorb delays without cascading consequences

Beneath each is the same premise: the user’s life is frictionless enough to comply. This is where the gap opens. Real lives collide with system design because the system assumes a stability most people simply do not have.

II. How Design Exclusion Creates “Unreasonable” People

When someone deviates from the expected pattern—misses a deadline, shows up without a document, responds too slowly—the system performs a familiar attribution error: it fails to see the mismatch as a design constraint and instead treats the deviation as a personal failure.

Consider the lives most often labeled “unreasonable”:

A parent caring for a sick child.

A shift worker whose schedule changes weekly.

A disabled person with fluctuating energy or health.

An immigrant navigating conflicting documentation requirements.

A student juggling work, debt, and irregular hours.

A gig worker dependent on volatile earnings and algorithms.

None of these lives are unusual. They only look “unreasonable” relative to an infrastructure designed to exclude them.

III. Systemic Rigidity vs. Human Complexity

Systems that demand consistency from inconsistent lives predictably misinterpret normal complexity as disorder.

A rigid system interacting with a variable world reads variance as noncompliance.

A missed deadline is interpreted as irresponsibility.

A rescheduled appointment becomes noncompliance.

A delayed upload becomes negligence.

A conflicting obligation becomes excuse-making.

It is not people who are failing; it is the system’s tolerance that has evaporated. Because the imagined Reasonable Person is treated as the default standard user, everyone else gets sorted into an informal category: the “unreasonable people” who supposedly cannot manage their lives.

IV. The Loss of Human Judgment in Automation

In more flexible eras, mismatches were absorbed by human judgment—clerks who understood context, caseworkers who recognized competing demands.

As interpretive layers are replaced by portals, automated triggers, and rigid thresholds, the system’s capacity to recognize legitimate variation disappears.

The burden of coherence moves outward: human variability is flattened so systemic rigidity can be maintained.

What used to be handled with discretion is now handled with denial. There is nowhere in the workflow to register that a “non-compliant” person is simply someone whose life does not match the imagined script.

V. Reframing User Failure as Design Flaw

Once this dynamic comes into view, responsibility becomes easier to locate.

The problem is not that individuals are inconsistent. The problem is that infrastructures demand a level of consistency real life does not allow. What looks like failure is often nothing more than evidence of competing realities that the system refuses to acknowledge.

If a system only works for people whose lives never collide with anything else, then the system is the one that is unreasonable.

Seen this way, “unreasonable people” are often just the ones whose lives reveal where the model breaks. Their so-called failure is a description of the system’s narrowness, not of their worth.

Why Systems Lean on Our Backs: The Politics of Load Bearing

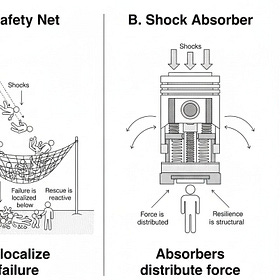

Variance is inevitable. Illness, economic downturns, climate shocks — they all arrive eventually. The political question isn’t if they come, but who absorbs the hit. Every society already runs a risk-management plan, making every government an engineering choice. What differs is not the existence of shocks, but

VI. Three Strategies for Resilient System Architecture

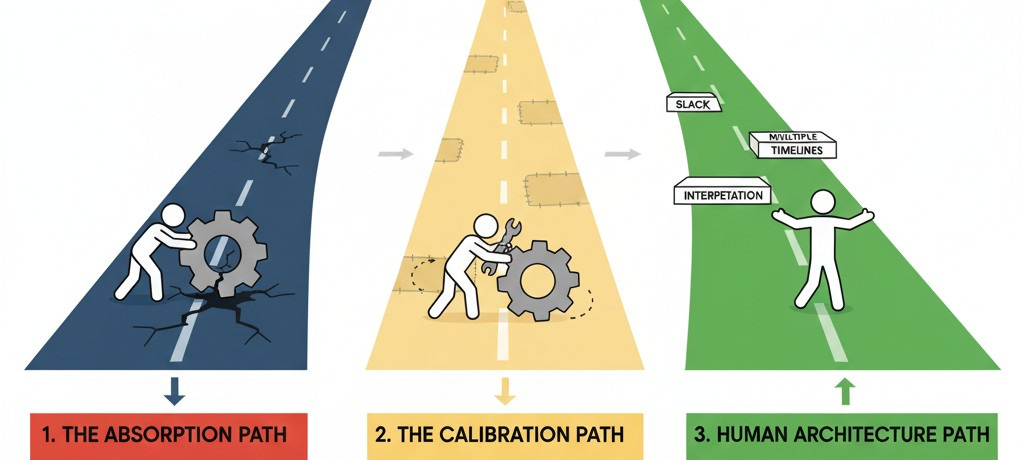

There are three possible paths forward.

1. The Absorption Path: Individuals Bend

Continue as we are. People keep absorbing the mismatch, performing heroics to stay compliant. Their compensatory labor is misread as competence. Their collapse is misread as personal fault.

“Unreasonable people” are instructed to try harder.

2. The Calibration Path: Broaden the Model Slightly

Add flexibility, widen windows, soften edges.

Expect people to shield one another from the worse elements of the system.

This is helpful but brittle. As long as the incentives reward narrowness, broadened models regress toward the Reasonable Person's silhouette.

Calibration masks the problem; it does not resolve it.

3. The Human Architecture Path: Redesign for Real Life

The only durable option. Build systems that remain stable when people do not.

This means infrastructures with:

operational slack rather than minimum viable margins

interpretive capacity rather than binary thresholds

multiple timelines rather than one correct pace

accommodation for interruption, conflict, and return

logic that treats mismatch as diagnostic, not deviant

It is what accuracy, resilience, and fairness require.

A system designed for an imaginary person will always malfunction on contact with the world—and will keep calling that malfunction “unreasonable people.”