Why Systems Lean on Our Backs: The Politics of Load Bearing

The political question isn’t if shocks arrive, but where the load lands. This essay reframes “policy” as applied physics—and legitimacy as a system’s load-bearing capacity.

Variance is inevitable. Illness, economic downturns, climate shocks — they all arrive eventually. The political question isn’t if they come, but who absorbs the hit. Every society already runs a risk-management plan, making every government an engineering choice. What differs is not the existence of shocks, but where they land.

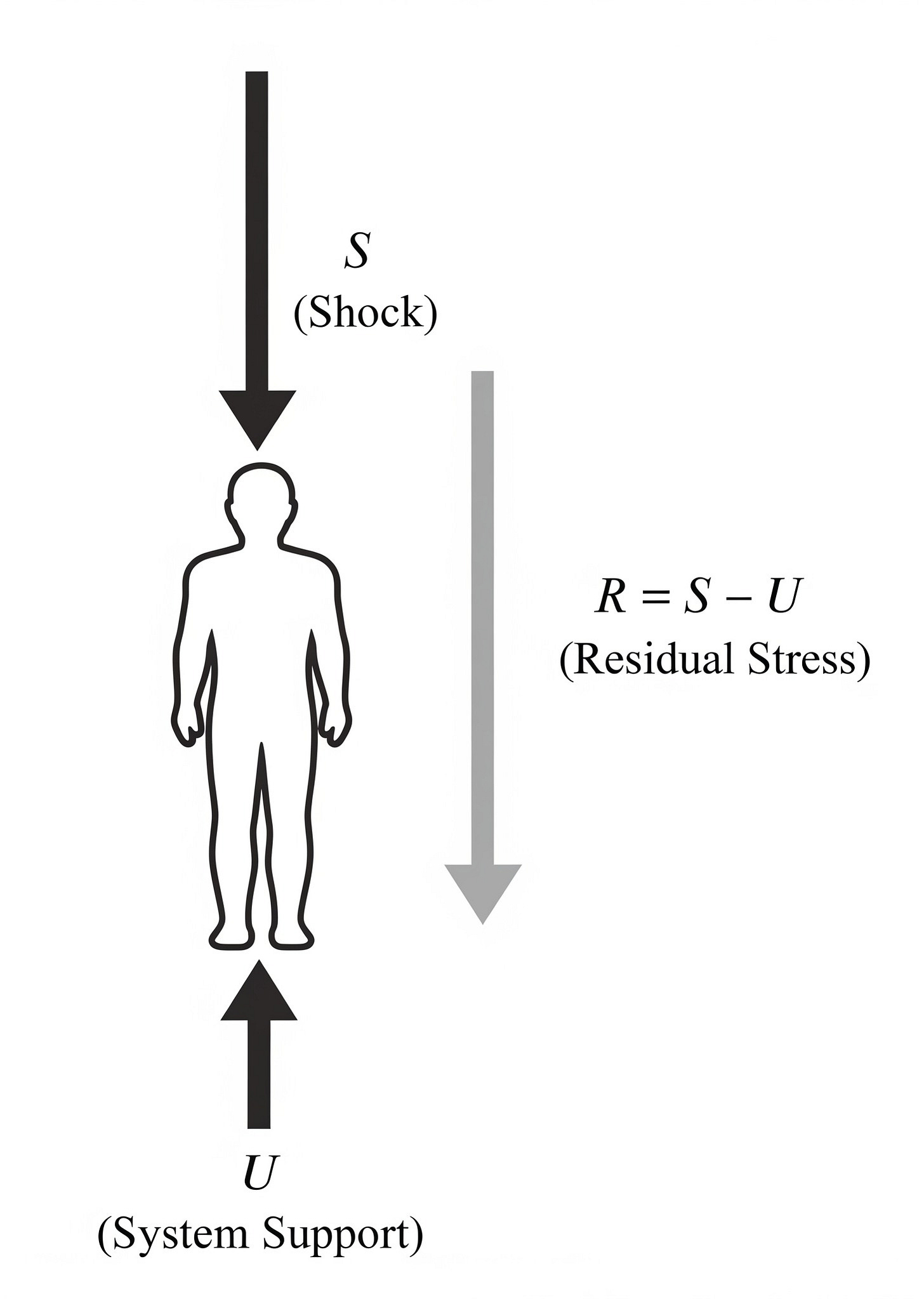

To see this clearly, picture a citizen sketched as a free-body diagram. A downward press S represents the shock: a layoff, an illness, a flood. An upward push U is the counterforce from the system: healthcare, unemployment benefits, housing. The remainder, the stress the person must carry alone, is a simple calculation: S − U. That leftover weight is not destiny or morality. It’s design. The strain on an individual is as measurable as gravity, which means politics is not metaphor but applied physics.

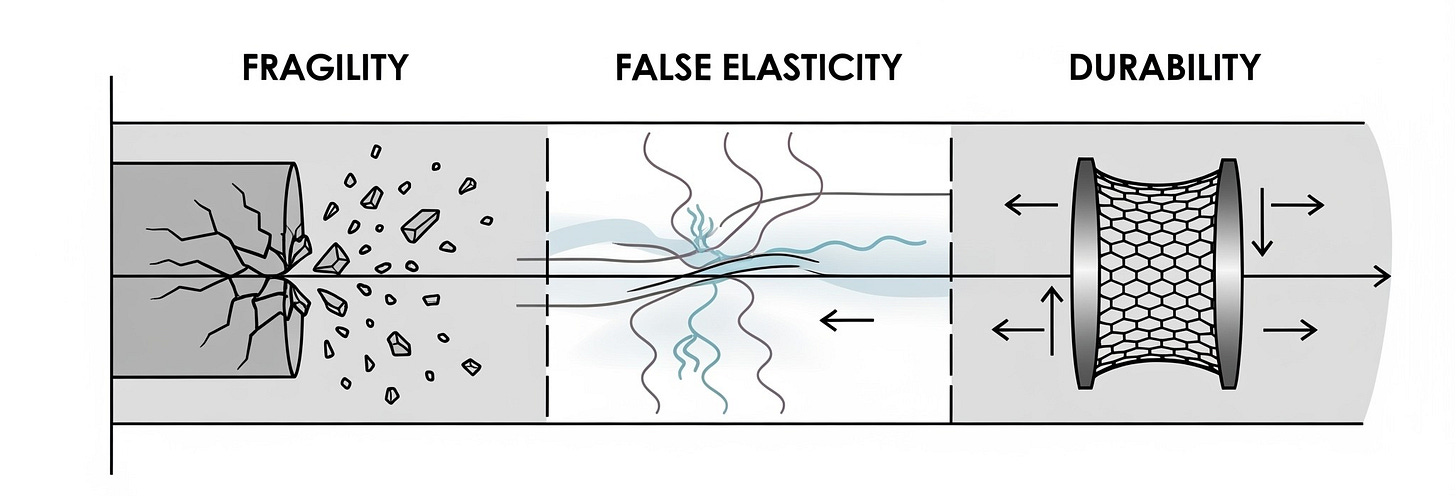

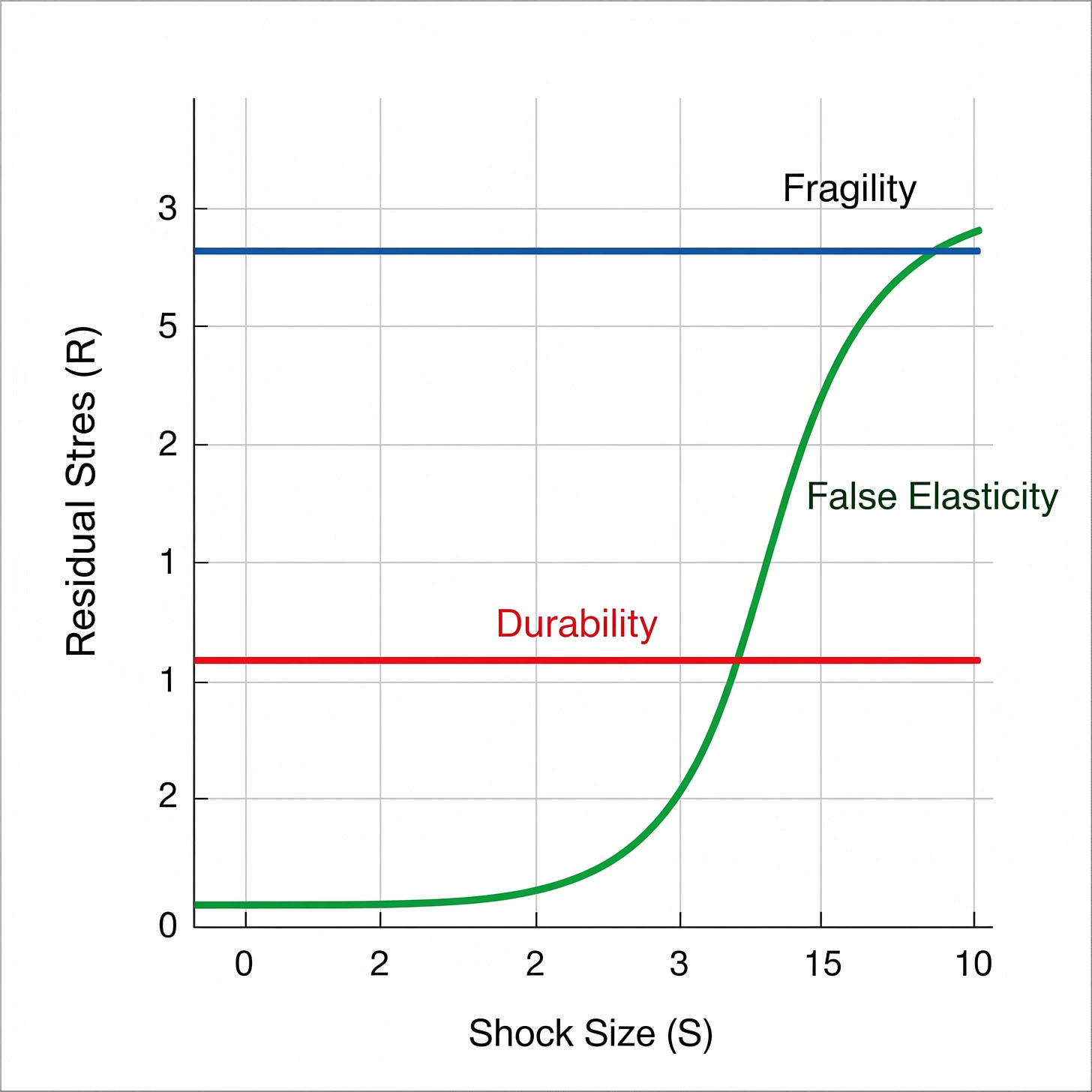

This simple equation reveals how different political systems perform under stress. A load-bearing lens shows three distinct architectures. The first is Fragility (People Pay), a system providing almost no counterforce, where “personal responsibility” is the routing rule and burnout is an expected output. At the other end is Durability (System Absorbs), where universal programs distribute shocks widely, metabolizing risk at population scale not as charity, but as sound engineering. In the middle sits today’s norm: False Elasticity (System Leaks). This system advertises flexibility but quietly channels stress onto targeted groups, fueling resentment while elites deflect anger toward scapegoats.

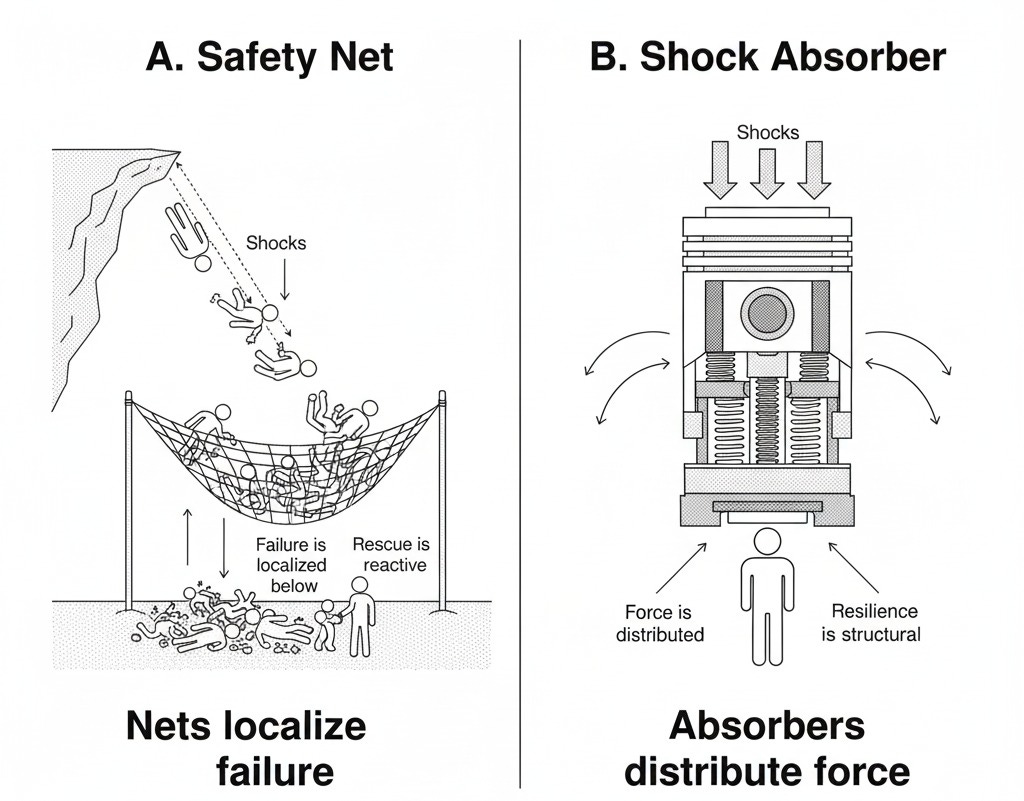

To build a durable system requires letting go of flawed metaphors. The “safety net,” for instance, has always been wrong. Nets catch a few who fall; Absorbers spread force across the entire frame. The state, reimagined, is not an emergency patch at the bottom but the central shock absorber, designed to dissipate impacts before they fracture lives.

Success, in this model, isn’t GDP. It’s how much weight the system carries without breaking its people.

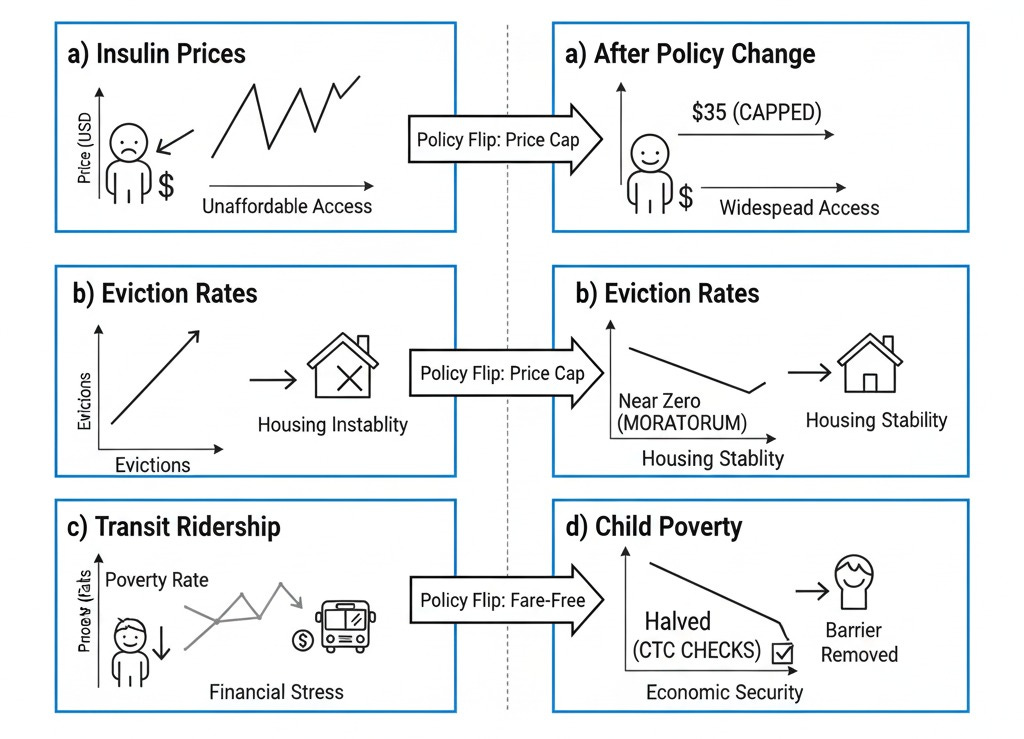

Every so often, the inevitability theater collapses and we see the proof that these outcomes are deliberate settings (Manufacturing “Inevitability”). When insulin was capped at $35, prices were revealed not as “the market” but as policy. When eviction freezes stopped mass housing loss, “supply and demand” was exposed as discretionary law. When the Child Tax Credit arrived as monthly checks, child poverty was nearly halved—and it spiked back the moment the program ended. Receipts like these prove fragility isn’t nature. It’s bookkeeping.

For decades, the perfect alibi for fragile design has been the ideal of “personal responsibility.” It’s an argument that masterfully reframes systemic stress as a personal failing, turning a predictable collapse into a moral defect (Long On Exclusion).

The message is blunt: we are designing fragility, and we will blame the people it breaks.

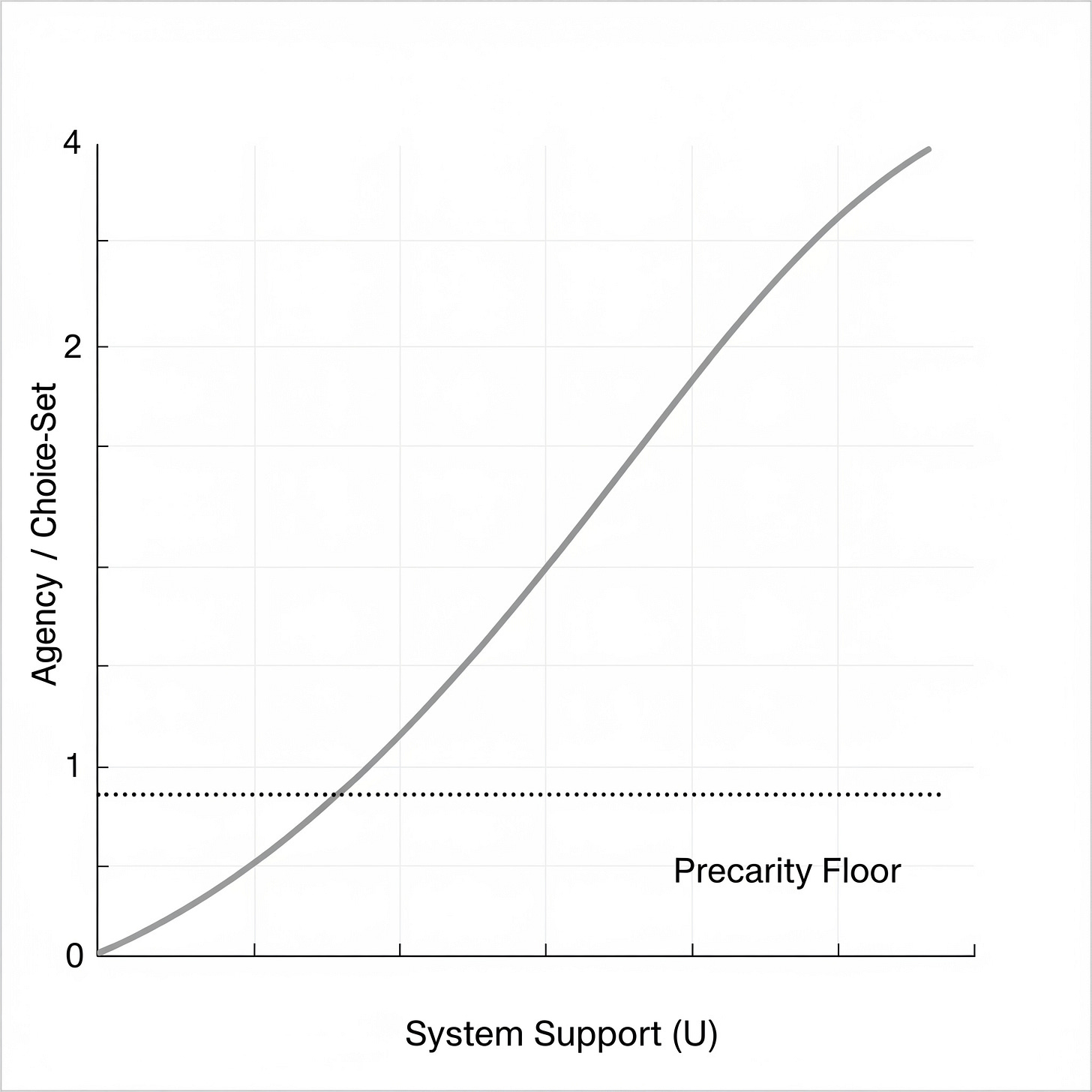

But if responsibility is an alibi, then what is freedom? We’re often told it’s the absence of support. Yet a person staggering under medical debt or the judgment of an algorithm is not free; they are coerced by precarity (Seemingly Neutral Systems). Real freedom requires a floor. It demands the upward force of durable systems that give people the margin to move, to choose, and to build.

Freedom isn’t subtraction; it’s the scaffolding needed to climb.

This connection between support and individual agency scales up directly to the highest political level, where it forms the basis of legitimacy. Legitimacy isn’t earned in speeches; it’s tested when shocks arrive. Systems that absorb variance deepen trust. Systems that dump or leak it corrode trust, exposing themselves as protection machines for the few. 2008 made it plain: the state absorbed risk for banks and bounced it onto homeowners. Early COVID replayed the script: institutions were bailed out while citizens scrambled for masks. These weren’t just policy failures; they were failures of legitimacy.

The mythology of “small government” dissolves under this frame. Choosing not to provide upward support is not neutrality; it’s an engineered decision to maximize exposure. “Do nothing” is still a setting that sets the load to land on people. There are no neutral systems (Refusability Is the Future of Design). Reduced to its forensic essence, politics asks a single question: Where does the load land? If it lands on people, fragility is the business model. If it leaks selectively, resentment is the fuel. And if it is absorbed collectively, durability is the source of legitimacy.

Politics is applied physics. Freedom is measured not by slogans but by net stress. And legitimacy belongs only to systems that can carry the load.

Build for variance, or you will be building for resentment.