The Capture of “Maintenance”

We must reclaim the maintenance that keeps people alive rather than the one that keeps systems standing.

Maintenance has always been with us. Roofs sagged, tools dulled, roads eroded, bodies faltered. People repaired what they could because survival required it. This older form of maintenance was neither glamorous nor philosophical; it was a rhythm, a habit, a way of moving with time rather than trying to subdue it. It kept things alive so they could keep changing.

But maintenance has not survived history unchanged. Somewhere between the factory floor and the modern state, between austerity budgets and glossy futurist manifestos, maintenance acquired a second meaning—one that looks like care but behaves like control. Today, two very different forms of maintenance share a single name, and much of our political confusion comes from mistaking the wrong one for the right one.

One is maintenance-as-sustenance: the kind I explored in To Be Is To Be Maintained. It creates slack, absorbs shocks, distributes load, and keeps people capable of weathering change. It is maintenance as the precondition for new worlds.

The other is maintenance-as-stasis: maintenance not as care but as containment, not as nourishment but as continuity enforcement. This is the maintenance I critiqued in The Death of Slack and Human as Crumple Zone—maintenance that treats people as buffers for system fragility and regards any rupture as a threat to be managed, suppressed, or moralized away.

The story of modernity is the story of how the first became eclipsed by the second—how the maintenance that keeps people alive was conscripted into the work of keeping institutions alive.

From Rhythm to Regime

In pre-modern life, maintenance was cyclical and local: tending fields, mending tools, patching walls, restoring what time had worn down. It was the communal labor of staying in the world together. No one believed that repair could prevent change; repair existed to permit change by absorbing its costs.

Industrial capitalism broke that symmetry. A factory’s profitability depended on its machines running continuously. Maintenance was no longer cyclical; it was constant. No longer communal; it was professionalized. No longer adaptive; it became a discipline of compliance and record-keeping. The point wasn’t to sustain life but to sustain output.

Maintenance-as-stasis was born the moment maintenance became a precondition for profit.

Across the twentieth century, this logic expanded. States took responsibility for infrastructure, and public maintenance became the backbone of legitimacy. Roads must not buckle, bridges must not collapse, grids must not blink. Much of this was genuinely life-giving—maintenance-as-sustenance at scale—but it also centralized the question of whose life conditions were worth maintaining.1

Then came the neoliberal turn, which did not simply neglect maintenance but withdrew it strategically. Sociologist Ruth Wilson Gilmore calls this organized abandonment—the deliberate starving of certain systems and communities while elites celebrate a rhetoric of fiscal prudence.

Maintenance-as-stasis became the engine of premature death. The system survives by letting specific populations fall apart.

Moralizing the Wrong Kind of Maintenance

The most insidious development of the last forty years is not the withdrawal of maintenance—it is the moralization of maintenance-as-stasis. As public institutions hollowed out, people were encouraged to treat patching the resulting holes as a personal virtue.

We can see this everywhere:

Teachers in crumbling buildings are praised for “going above and beyond,” as if crowdfunding air filters were a sign of devotion rather than evidence of state abandonment.

Nurses working double shifts under dangerous ratios are celebrated for their “resilience.” Their sacrifice becomes the maintenance plan.

Public libraries quietly become de facto warming centers, social services hubs, and crisis shelters—and we praise them for their “community spirit” instead of funding the infrastructures that would make that labor unnecessary.

Gig workers carry the volatility of platforms designed to shed every cost possible and are told they are “entrepreneurs of themselves.”

In each case, the world is maintained not through structural repair but through extracted virtue. Institutions weaponize the language of “care,” “community,” “responsibility,” and “stewardship” to shame individuals into doing unpaid maintenance labor that keeps a decaying system upright.2

People internalize these expectations. They take pride in bailing out sinking ships. They congratulate themselves for being reliable where systems are brittle. They mistake overextension for moral character. In this way, maintenance-as-stasis becomes self-reproducing. People become the buffer that eliminates both the evidence of failure and the demand for repair.

When Maintenance Becomes Temporal Containment

The 21st century has intensified this capture. As governments, corporations, and cultural institutions lose confidence in their ability to imagine new futures, maintenance stops being a strategy for sustaining life and becomes a strategy for suppressing change.

“Resilience” means returning to a status quo that is killing people.

“Stability” means preserving institutions that no longer function.

“Preservation” becomes a way to shut down demands for redesign.

“Repair” becomes a euphemism for prolonging the present.

This is not maintenance-as-sustenance—it is maintenance-as-temporal-containment: a politics of the forever now, the same temporal logic I diagnosed in The Pyrrhic Condition, where systems perfect their own performance while hollowing out the future.

Governments speak of “weathering the crisis,” “holding firm,” “restoring normalcy.” Corporations speak of “reliability,” “continuity,” “operational excellence.” But behind this language is a refusal to redesign systems that are structurally incapable of serving the world they now govern.

Maintenance here functions as a defense of the present against the possibility of anything else.

Maintenance as Elite Pastime

Nothing illustrates the contemporary capture more cleanly than the emerging “maintenance movement,” crystallized in the forthcoming Stripe Press book Maintenance: Of Everything by Stewart Brand.

Its aesthetic is seductive: glossy photos of handcrafted tools, sailboats, mechanical clocks; the romance of tinkering; the spiritual discipline of upkeep. But its politics are disingenuous.

Brand’s Long Now philosophy has always sought to “stabilize” civilization against “short-termism.” But when stability becomes the highest value in a broken system, “long-term thinking” becomes a euphemism for infinite stasis.

“The book explores the insights that can be gleaned from the maintenance of sailboats, vehicles, and weapons…It invites us to understand not only the profound impact maintenance has on our daily lives but also why taking responsibility for maintaining something—whether a motorcycle, a monument, or our planet—can be a radical act.”

Stripe Press packages maintenance not as the gritty, precarious struggle of tenants dealing with black mold or communities fighting for clean water, but as a design problem for the already-insulated. Maintenance becomes a luxury hobby, a lifestyle virtue. It aestheticizes survival while obscuring who currently can’t afford to survive.

It is no coincidence that Stripe—a financial infrastructure company—would champion such a vision. For financial capital, the only maintenance that matters is the maintenance of transactionality: uptime, reliability, seamless flows of money. They want a world that works (for commerce), not a world that cares (for people).

In their hands, maintenance becomes a philosophy of infrastructural obedience.

What the Capture Has Cost Us

Across these arcs, the pattern is unmistakable:

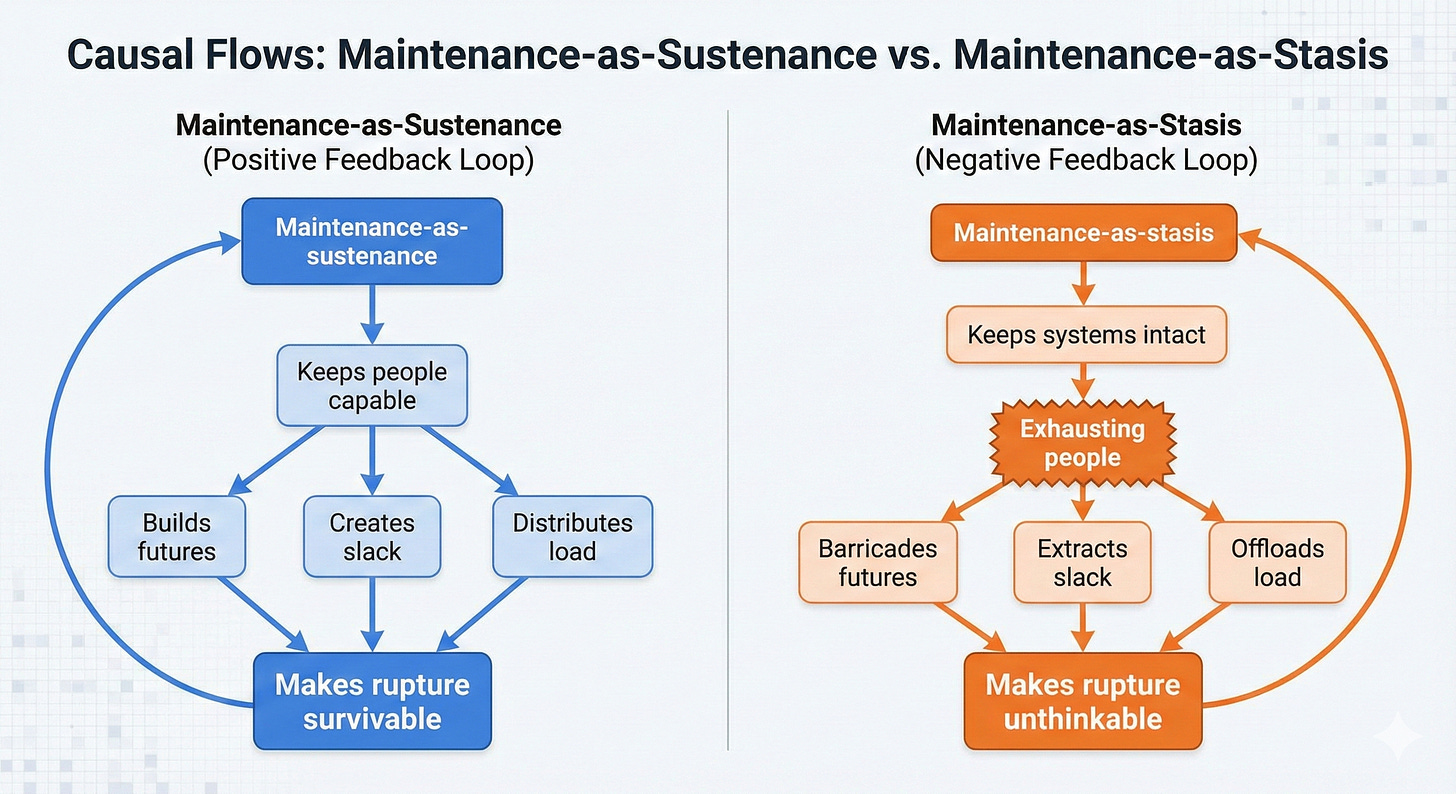

Maintenance-as-sustenance keeps people capable.

Maintenance-as-stasis keeps systems intact by exhausting people.

Sustenance builds futures; stasis barricades them.

Sustenance creates slack; stasis extracts it.

Sustenance distributes load; stasis offloads it.

Sustenance makes rupture survivable; stasis makes rupture unthinkable.

We now live in a world where institutions survive by letting people fall apart.

The Maintenance We Must Reclaim

We cannot reject maintenance. We need it more than ever. But we must choose the right one.

We must reclaim maintenance-as-sustenance:

maintenance that restores capacity rather than consuming it

maintenance that distributes harm rather than concentrating it

maintenance that builds redundancy rather than demanding heroism

maintenance that prepares the world for change rather than prevents it

maintenance that treats people not as load-bearing components but as lives worth making room for

This kind of maintenance is not nostalgic. It is not soft. It is not slow. It is the only maintenance that allows for the world we desperately need but have not yet built.

Maintenance-as-stasis keeps civilization running in place.

Maintenance-as-sustenance keeps civilization capable of moving at all.

Only one of these can carry us forward.

This is the seed of what I later called Critical Bioengineering, where the design of failure determines which bodies absorb which harms.

This is the dynamic I exposed in Sanctiphagy: people are consumed to preserve the institution.