Stop Blaming Dopamine

I used to believe my late-night scrolling was purely a personal failing—maybe I had “no willpower,” or my brain was “wired for dopamine hits.” That was the narrative fed to me by pop neuroscience and digital minimalists alike.

Then I spent four years (2013–2017) as a product manager at Doximity, the so-called “LinkedIn for doctors.” On the surface, it’s nothing like a typical ad-driven social app: it’s built for busy physicians to network, get industry updates, and handle telehealth. I know many people there who are genuinely committed to improving healthcare.

But from the inside, I also saw how capturing and retaining user attention was quietly central to Doximity’s design—just like it is for Facebook, TikTok, or any other engagement-driven platform. If a professional network for doctors relies on “time on platform,” imagine how critical user retention must be for massive consumer apps.

That’s what prompted me to rethink the scapegoat of “dopamine addiction.” Because while dopamine does play a part, a systemic model is what truly keeps us hooked.

A Window into Engagement Economics: Doximity’s Example

Many assume a “LinkedIn for doctors” is immune to “addictive” loops. After all, it’s not built around cute videos or drama. But beneath the professional facade, Doximity’s revenue streams highlight a similar reliance on sustained attention:

Pharmaceutical Marketing & Brand Awareness

Pharma companies pay to show targeted “educational campaigns” or brand ads to specific specialties—cardiologists, oncologists, etc. The more time doctors spend on the platform, the more likely they’ll see these ads or sponsored articles.Job Listings & Career Tools

Hospitals and clinics pay for job postings, but only get value if doctors log in often enough to notice them. If usage wanes, that revenue stream falters.Enterprise Solutions & Telehealth

Doximity sells telehealth features to hospitals. Those enterprise clients expect proof that doctors actually use the platform—meaning frequent logins and robust session data.Sponsored Content & Medical Education

Articles, editorial features, and CME (Continuing Medical Education) modules can be underwritten by device makers or pharma sponsors. The more articles a doctor reads, the more “impressions” for sponsors.

So yes, Doximity genuinely helps doctors—through job alerts, medical news, telehealth solutions—but more user sessions also strengthen its business model. Even though the platform isn’t “addictive” in the sensational sense, the fundamental link between sustained engagement and revenue remains.

Micro-Optimizations: Small Nudges that Matter

Doximity doesn’t rely on endless cat videos, but subtle design tweaks still boost retention:

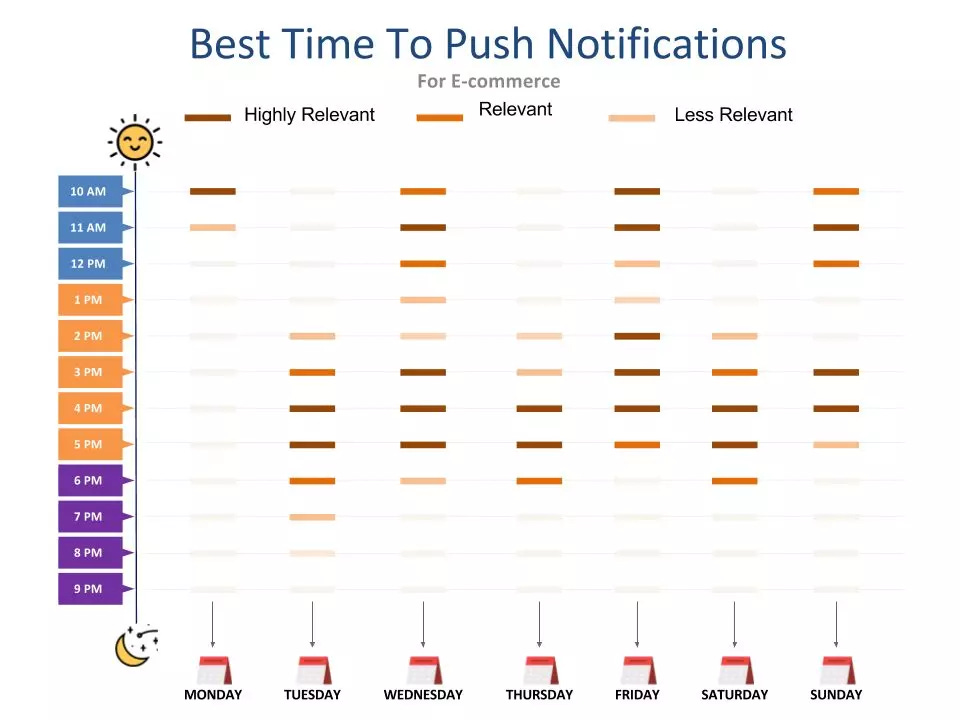

Notification Timing

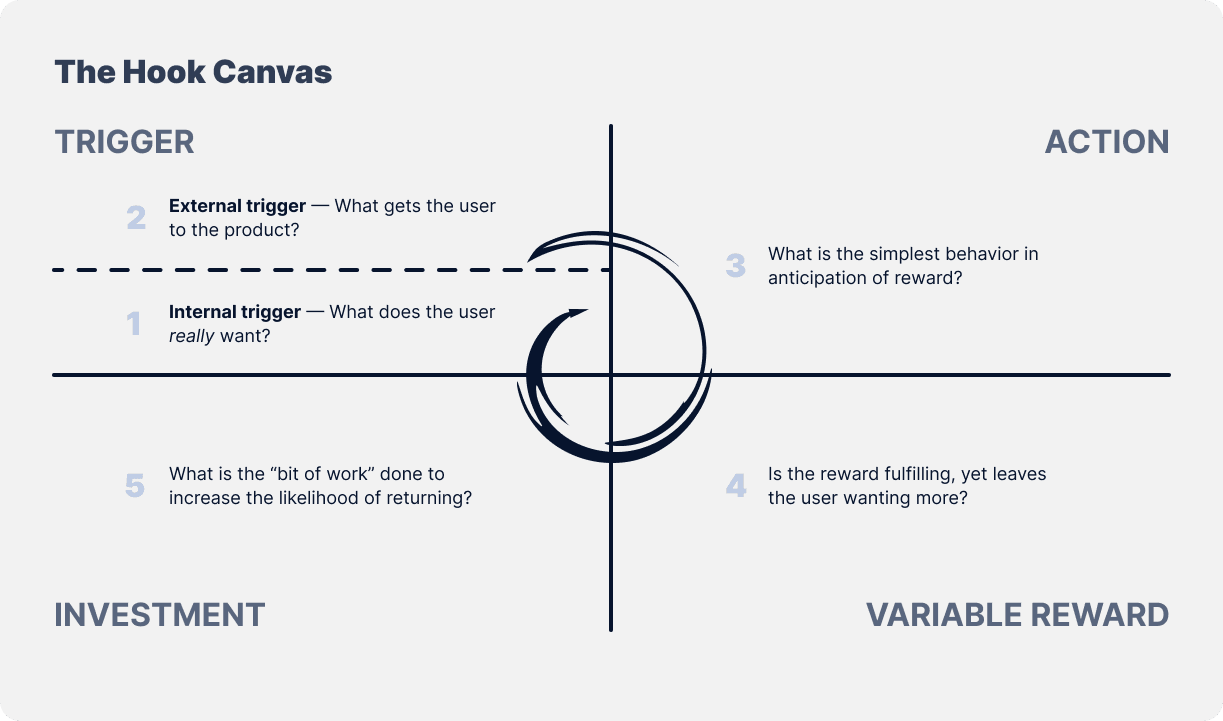

If a surgeon typically finishes OR cases late afternoon, that’s precisely when a “medical news” alert pings. Even a 0.3% bump in re-engagement means thousands more sessions per week, multiplied across the user base.Content Chaining

After reading one clinical news article, you see “related” updates or suggested CME modules. This might be educational, but it also keeps you around a bit longer—and each extra minute can expose you to more ads or sponsor content.Friction in Logging Out

Doximity doesn’t bury the “sign out” button as aggressively as some consumer apps do, but small shifts—like how prominent the exit option is—affect whether doctors fully disconnect or remain passively logged in.

These optimizations aren’t necessarily evil; many doctors find them helpful. But they demonstrate how a revenue model that depends on user presence inevitably orients the platform toward small changes that increase “time on site.”

If it’s true in a niche, “useful” tool for doctors, it’s exponentially more intense in mainstream social networks built around ad revenue.

It’s Not All About “Dopamine”

We often say, “I’m addicted to my phone—my dopamine circuits are shot.” Sure, neurotransmitters matter in habit formation, but focusing solely on “dopamine hijacks” personalizes the blame:

It Individualizes the Issue

If it’s about your dopamine or your lack of willpower, you become the problem. The sophisticated design tactics and multi-million-dollar budgets behind them get a pass.It Lets Platforms Off the Hook

Blame yourself for being “weak,” not the product teams A/B testing every UI element to keep you hooked.It Misses the Structural Logic

The real architect is a business model that translates user minutes into profit. That’s why platforms fine-tune experiences to maximize your presence.

As I discuss in Misreading Capitalist Realism, capitalist systems excel at reframing structural dynamics as personal flaws. Meanwhile, Temporal Justice examines how lacking offline resources—be it stable jobs or mental health care—drives more people into digital domains they can’t simply “log off” from.

Telling someone to “be more disciplined” or “delete the app” overlooks that many rely on platforms (like Doximity) for critical professional or social needs.

“Time Well Spent”: The Convenient Rebrand

When the spotlight turned on “addictive” tech, many big platforms trotted out “time well spent” or “meaningful interactions.” The idea? Instead of chasing raw session hours, they’d track “quality” usage. But as we saw in Doximity’s example, the core logic rarely changes if the platform’s viability still depends on consistent, repeated engagement:

They Claim to Care About ‘Quality,’ But Keep Measuring Engagement

“Meaningful interactions” is just a new metric. If user hours fall too much, advertisers or enterprise customers get nervous, and the platform adjusts to pull you back in.They Monetize Meaningful

Even “beneficial usage” (reading an in-depth medical piece or networking with peers) can be wrapped in sponsor messages or data collection, still fueling the profit engine.It’s PR, Not Structural Shift

“Time well spent” soothes critics, but does nothing about how “your time” is still the raw material for someone else’s profit. That fundamental tension remains unchallenged.

This is a pattern we see again and again: when industries face major pushback, they reframe the conversation in ways that deflect deeper demands for systemic change.

Think of the food industry’s “low-fat” marketing without tackling sugar-laden profits, or the fossil-fuel sector’s shift to “personal carbon footprints” to avoid corporate accountability. Now, social media does the same with “time well spent.”

Why ‘Log Off’ Alone Doesn’t Solve It

Some might say: “Just delete the app if it’s so manipulative.” But that’s naive, especially for:

Professionals

Doctors needing job leads or telehealth clients can’t just ditch Doximity. Gig workers relying on rideshare or delivery apps can’t simply walk away from their income source.Communities

Activists, diaspora communities, and marginalized groups often rely on digital networks for crucial support or organizing. If local offline resources are scant, “stepping away” can feel impossible.Systemic Constraints

Poor offline infrastructure—limited job security, expensive healthcare, underfunded community spaces—pushes more of our lives online. Telling people to “just have more willpower” overlooks these structural failings.

Hence the flaw in personal “detox” solutions: they might help you individually, but they don’t address the architecture that sees every second of user time as revenue potential.

Stop Blaming Dopamine—Question the System

Ultimately, “dopamine addiction” is an oversimplification. Yes, our brains enjoy novelty, but entire teams systematically harness that craving, driven by monetary incentives to keep us glued. “Time well spent” is just a polished narrative that doesn’t sever the link between our time and someone else’s revenue.

A platform like Doximity—legitimately valuable for doctors—still invests in micro-optimizations to raise “time on site.” Multiply that logic in social behemoths, and you get a sophisticated machine that claims to care about your well-being while quietly profiting from each extra minute you stay.

That’s why telling individuals “use more willpower” or “just log off” addresses the symptoms, not the structure. If we truly want to move past guilt-ridden doomscrolling or moralizing about “dopamine hijacks,” we need policy-level approaches, alternative business models, and offline safety nets so “logging off” isn’t a sacrifice of jobs or community.

The real question isn’t whether your brain seeks dopamine—it’s who profits when you can’t leave, why infinite feeds are standard, and how we can demand a digital ecosystem that prioritizes user well-being over indefinite engagement. Until then, “time well spent” is more of a PR bandage than a genuine fix. We deserve a world where platforms serve us—rather than treating our attention as raw material for corporate gain.