Tech Abstinence Fails to Challenge Surveillance Capitalism

Tech abstinence—unplugging from social media, deleting apps, limiting screen time—has been embraced as a response to digital fatigue, surveillance, and the mental health impacts of constant connectivity. Silicon Valley whistleblowers, wellness advocates, and tech minimalists present unplugging as a route to reclaiming privacy, mental health, and freedom from corporate control.

Books like Cal Newport’s Digital Minimalism advocate for reduced engagement, while high-profile documentaries like The Social Dilemma have fueled growing public discomfort with the exploitative practices of Big Tech.

However, this narrative of tech abstinence obscures a deeper truth: while personal disconnection may offer relief from the anxiety of constant engagement, it does nothing to challenge the structural forces driving digital surveillance and data commodification. In fact, by focusing on personal solutions, tech abstinence can divert attention away from the larger systems that underpin surveillance capitalism.

This essay argues that tech abstinence offers an illusion of resistance, reinforcing neoliberal ideals of individual responsibility while allowing Google, Facebook, Amazon, and other tech giants to remain unaccountable. True resistance lies not in personal disengagement but in collective action and systemic change that directly challenge Big Tech’s hold over the digital economy.

The Illusion of Control in a Post-AI Era

At the heart of the tech abstinence movement is the promise of control—the idea that by curbing our digital habits, we can reclaim our autonomy in an era of pervasive surveillance. Advocates like Cal Newport suggest that reducing engagement with digital platforms will help individuals escape the attention economy, regain their focus, and create more meaningful, intentional lives.

However, as the rise of artificial intelligence (AI) accelerates, this notion of control becomes increasingly tenuous. The AI-driven algorithms that power platforms like Facebook, TikTok, and YouTube have become more sophisticated, adapting in real-time to users’ behaviors and interactions, regardless of whether they are logged into a platform or not. Even as individuals opt-out of these services, their data continues to be harvested, analyzed, and monetized through other vectors, such as smart home devices, facial recognition technology, and AI-enhanced surveillance embedded in public and private spaces.

Facebook continues to track users through shadow profiles, compiling data from third-party apps, cookies, and websites—even if the individual has never created an account.

Google collects information across the web through its vast advertising ecosystem, including sites that use Google Analytics, meaning even if users switch to privacy-focused alternatives, they still generate data that flows back into Google’s infrastructure.

Amazon’s reach extends beyond e-commerce, with Amazon Web Services (AWS) hosting cloud infrastructure for companies, governments, and organizations globally, making it almost impossible to disengage entirely from their ecosystem.

The accelerating use of AI surveillance tools—from predictive policing algorithms to emotion-recognition software in schools and workplaces—demonstrates that personal disconnection is a hollow gesture in the face of the technological systems embedded in every facet of modern life. AI-powered surveillance systems do not require individual participation to collect, categorize, and exploit personal data. As these systems evolve, personal choices, such as unplugging from social media or switching to alternative search engines, become largely symbolic acts that fail to address the ubiquity of digital surveillance.

The Commodification of Digital Disconnection

Ironically, the growing desire to unplug has itself been commodified by the very system that tech abstinence seeks to escape. Disconnection has become a luxury product marketed to the privileged few who can afford to step away from their devices.

Luxury digital detox retreats—where participants pay thousands of dollars to disconnect in serene, tech-free environments—are increasingly marketed to overworked professionals seeking respite from the digital grind. These experiences turn abstinence into a status symbol rather than a meaningful form of resistance.

Screen-time management apps like Freedom, Forest, and Moment sell themselves as tools to help users reclaim their time. However, these apps are often embedded in the same ecosystem of digital dependency they claim to combat, utilizing gamification techniques to keep users coming back for more.

Apple’s Screen Time feature, while positioned as a tool to help users manage their device usage, ultimately profits from the same attention economy it claims to regulate. Apple continues to generate profits from device sales and app engagement, even as it promotes digital well-being.

The commodification of abstinence reflects a broader trend in which the desire for privacy and control is packaged and sold back to consumers. This mirrors the dynamic seen in green consumerism, where eco-friendly products are sold as personal solutions to systemic environmental crises.

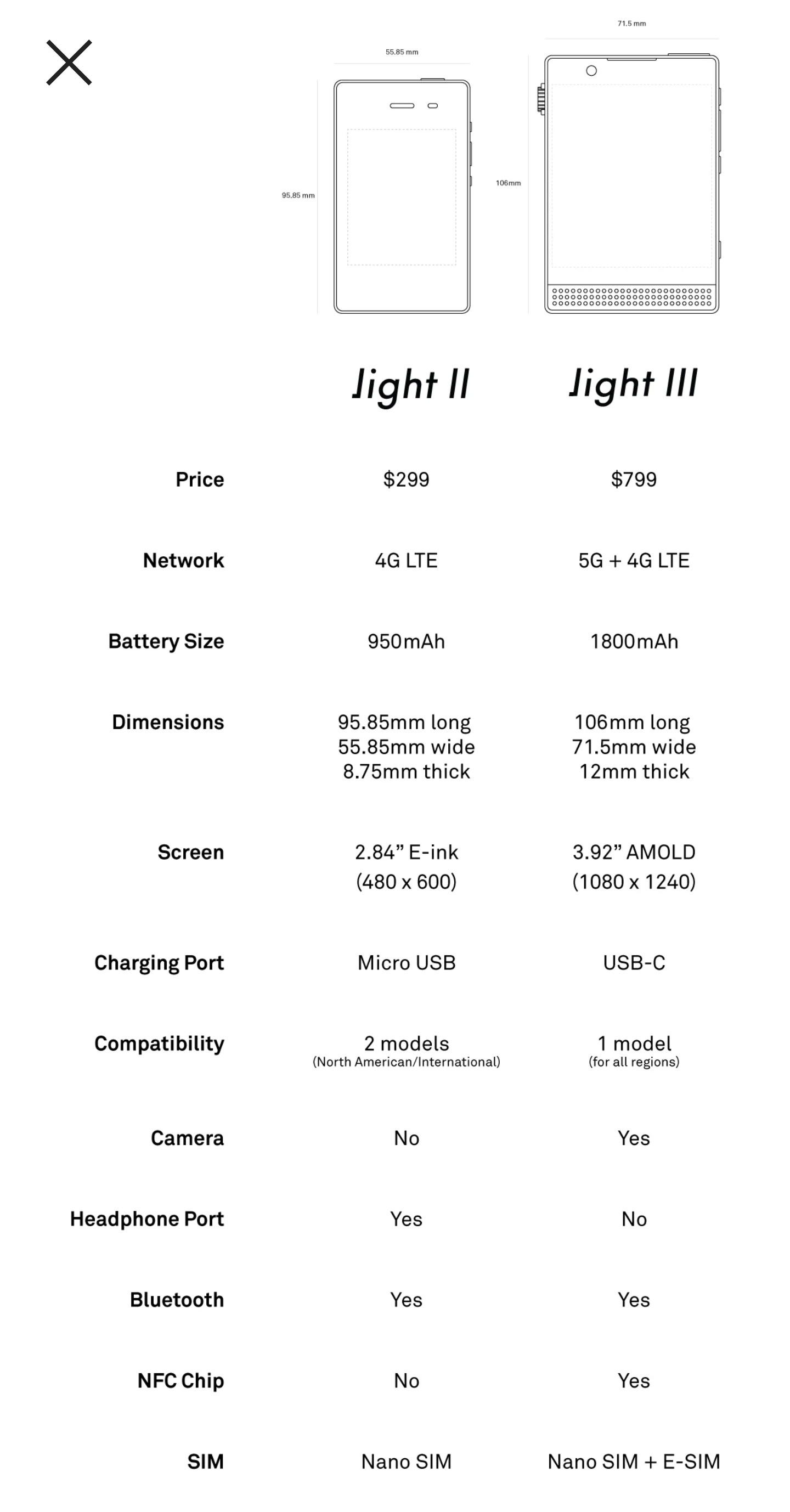

Similarly, the tech industry offers personalized solutions—such as digital detoxes, screen time trackers, and minimalist smartphones—that obscure the structural problems at the heart of surveillance capitalism.

The Privilege of Unplugging in a Post-Pandemic World

While tech abstinence is often framed as a universal solution, it is a privilege available to a select few. For millions of people, particularly in the gig economy and creative industries, digital platforms are not optional—they are essential for economic survival.

Freelancers, small business owners, and content creators rely on platforms like Instagram, YouTube, Etsy, and LinkedIn to secure clients, promote their work, and maintain visibility. Disconnecting from these platforms would mean economic peril for many who rely on these tools to generate income.

Marginalized communities use social media for organizing and visibility. Movements like Black Lives Matter, #MeToo, and Indigenous rights campaigns have leveraged platforms like Twitter and Instagram to amplify their voices and mobilize support. In this context, unplugging can mean silencing oneself and withdrawing from critical channels of activism and advocacy.

The COVID-19 pandemic only deepened reliance on digital platforms, as work, education, and social interaction shifted online. For workers in precarious economic situations, tech abstinence is not an option but a luxury that would cut them off from vital income streams, education, and even healthcare.

Framing disconnection as a universal solution ignores the economic realities that make unplugging unfeasible for so many.

As reliance on digital platforms intensifies, especially in a post-pandemic world, advocating for tech abstinence risks further marginalizing those who are already most vulnerable to economic exploitation and digital exclusion.

Tech Abstinence as a Neoliberal Fantasy

The core issue with tech abstinence is that it reflects a neoliberal logic, which shifts responsibility for systemic problems onto individuals. Just as green consumerism urges individuals to shop their way out of environmental crises, tech abstinence presents disconnection as a personal choice that can solve the larger issue of surveillance capitalism.

This narrative serves to depoliticize the problem, making it a matter of individual behavior rather than corporate or governmental accountability. It suggests that users themselves are to blame for the exploitative nature of digital platforms, implying that personal discipline and digital minimalism can fix what is, in reality, a structural issue.

In reality, surveillance capitalism is a system designed to extract data and profit from individuals regardless of their personal choices.

Framing the problem as one of overuse or screen addiction distracts from the need for collective action and regulatory intervention to address the concentration of power in the hands of Big Tech monopolies.

Reclaiming Digital Spaces in a Surveillance Economy

The real challenge lies not in retreating from technology, but in reclaiming digital spaces from the control of surveillance capitalism. Solutions will not come from personal disconnection but from community-driven alternatives that prioritize privacy, user control, and collective ownership over profit.

Platform cooperatives, such as Stocksy or Up & Go, offer models where workers own and manage the platforms they use, providing alternatives to the exploitative structures of the gig economy.

Open-source software, such as Signal and Mastodon, provide decentralized alternatives to corporate platforms, where users have greater control over their data and interactions.

Data cooperatives and data trusts allow users to collectively manage and control their data, reclaiming privacy from tech monopolies and offering a more democratic model of digital engagement.

By fostering community-driven infrastructure, such as local mesh networks and open-source platforms, we can resist the dominance of surveillance capitalism without relying on state intervention or top-down regulation.

Instead of retreating from technology, we should seek to transform the way it is structured and governed.

The problem with tech abstinence is that it offers a personal escape while leaving the infrastructure of surveillance capitalism intact. Real resistance requires more than disconnection; it demands collective action and community-driven solutions that challenge the foundations of corporate control.