How I Learned to Laugh at 'Inevitable'

The powerful have always used the language of weather and physics to enforce their will. The best counter isn't a better argument—it's seeing the absurdity of the play itself.

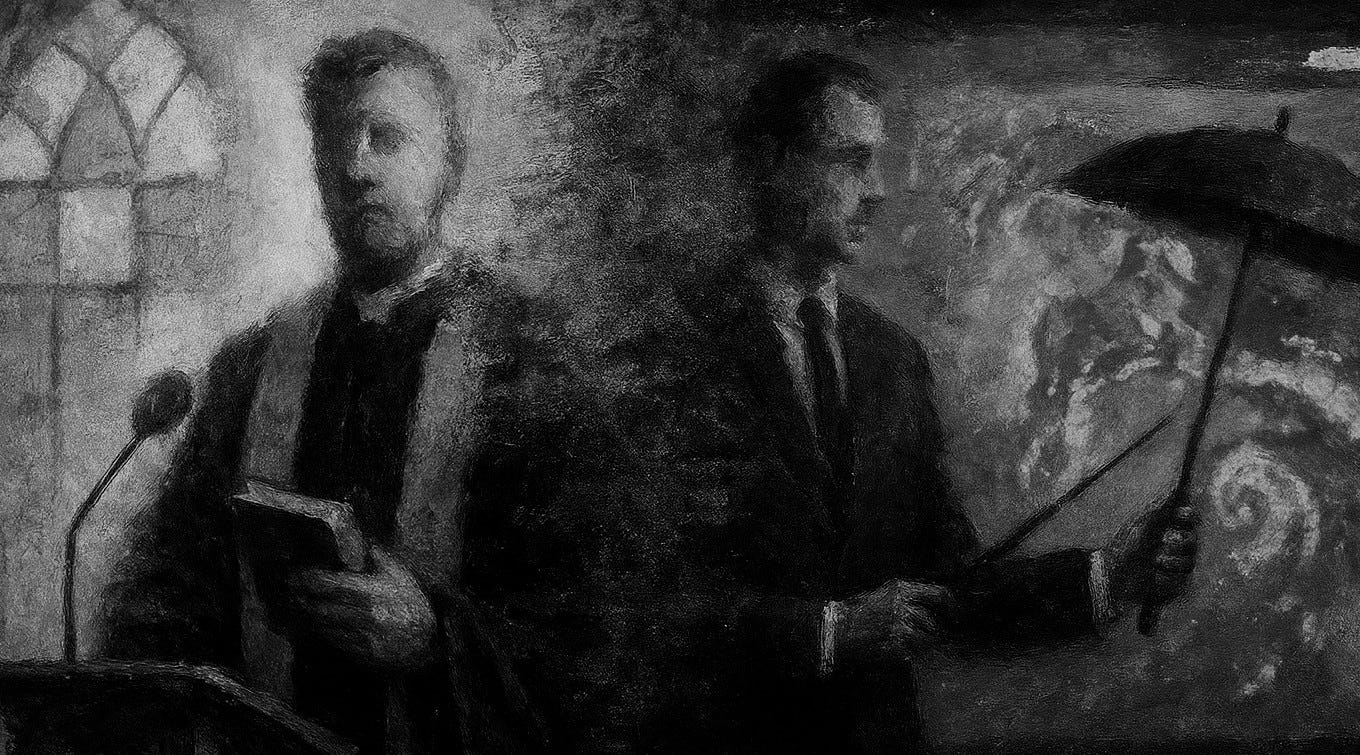

Inevitability always arrives in costume; it wants the room to believe it’s a law of nature, so it borrows the robes of weather, gravity, and time. Memos speak of “headwinds.” Dashboards announce that “change is no longer possible.” Executives insist that “everyone’s already on it.” The cadence is half-pastor, half-weatherman—grave enough that you’re meant to stop arguing.

But nothing natural is happening in those rooms.

What actually moves are pens across appropriations, toggles in accounting systems, and contracts narrowed by procurement specs. What shifts are risks pushed downward, choices disguised as fate.

That’s why it’s so fragile: if inevitability were truly gravity, it wouldn’t need a press release.

The humor comes from letting the costume slip. Imagine the market sulking like a roommate who wasn’t invited out. Picture "macro conditions" unable to open a jar, or "progress" locking itself out of Gmail again. Once these abstractions collapse to kitchen scale, their mystique shrivels. It’s harder to genuflect before destiny when you’ve pictured it fumbling with the Wi-Fi.

The vocabulary is equally flimsy. “Restructuring.” “Resilience.” “Efficiency.” These are words polished until they shine, then deployed like weapons. Their effect depends on solemn delivery, on straight faces. Place them next to the harm they describe—layoffs, abandonment, risk dumped downward—and the decoration looks garish, like rhinestones glued to a blade. The laugh that breaks out is not cruelty; it’s the recognition of how cruel the disguise always was.

This script has been on tour for centuries. Slaveholders called bondage the “natural order.” Industrialists framed exhaustion as “progress.” Cold War planners dressed brinkmanship as destiny. Thatcher built an entire ideology on four words: There Is No Alternative. Today’s technocrats repeat the lines, insisting regulation will “drive innovation overseas,” that adoption is “automatic,” and that the harms are “character-building.” The actors change, but the play remains the same.

Sometimes, inevitability has to manufacture its own proof. Hiring freezes are staged to make attrition look like a crisis. Pilot programs are designed so that reversal seems reckless. Markets are nudged into panic until the panic itself confirms the forecast. The fragility is built first, then cited as destiny. Watching that feedback loop is funny in the bleak way slapstick is funny: they slip on the banana peel they carefully placed themselves.

The sharpest tool of inevitability isn’t data or dashboards. It’s despair—the feeling that nothing can be done, that the script has already been written.

That’s where laughter matters.

A dark laugh doesn’t erase exhaustion, but it makes despair breathable. It opens a little space in the room, enough to stop suffocating, enough to keep refusing.

And there is one more crack in the façade: language never stays put. Executives believe their memos script the future. But once their phrases become punchlines, the script no longer belongs to them.

“Headwinds” shifts from a sober justification to a running joke. The room that laughs now holds the language. That redistribution of authorship is small, but real.

So picture inevitability embodied: a middle manager in a crown borrowed from the prop closet, PowerPoint slides for robes, and memos for scripture, reciting lines they don’t quite believe. From the balcony, the zipper is visible. And once you see the zipper, you can’t unsee it.

Inevitability only works if the room stays solemn. Once people laugh, the stagecraft falters, the euphemisms wilt, and the abstractions stumble.

Our laughter won’t rehire workers or cancel debt, but it can open the air back up enough for us to breathe.