How to Design for Cognitive Scarcity

Stop designing for the idealized "Hero User." Learn how to build resilient interfaces that work when your user is stressed, tired, and operating on 15% battery.

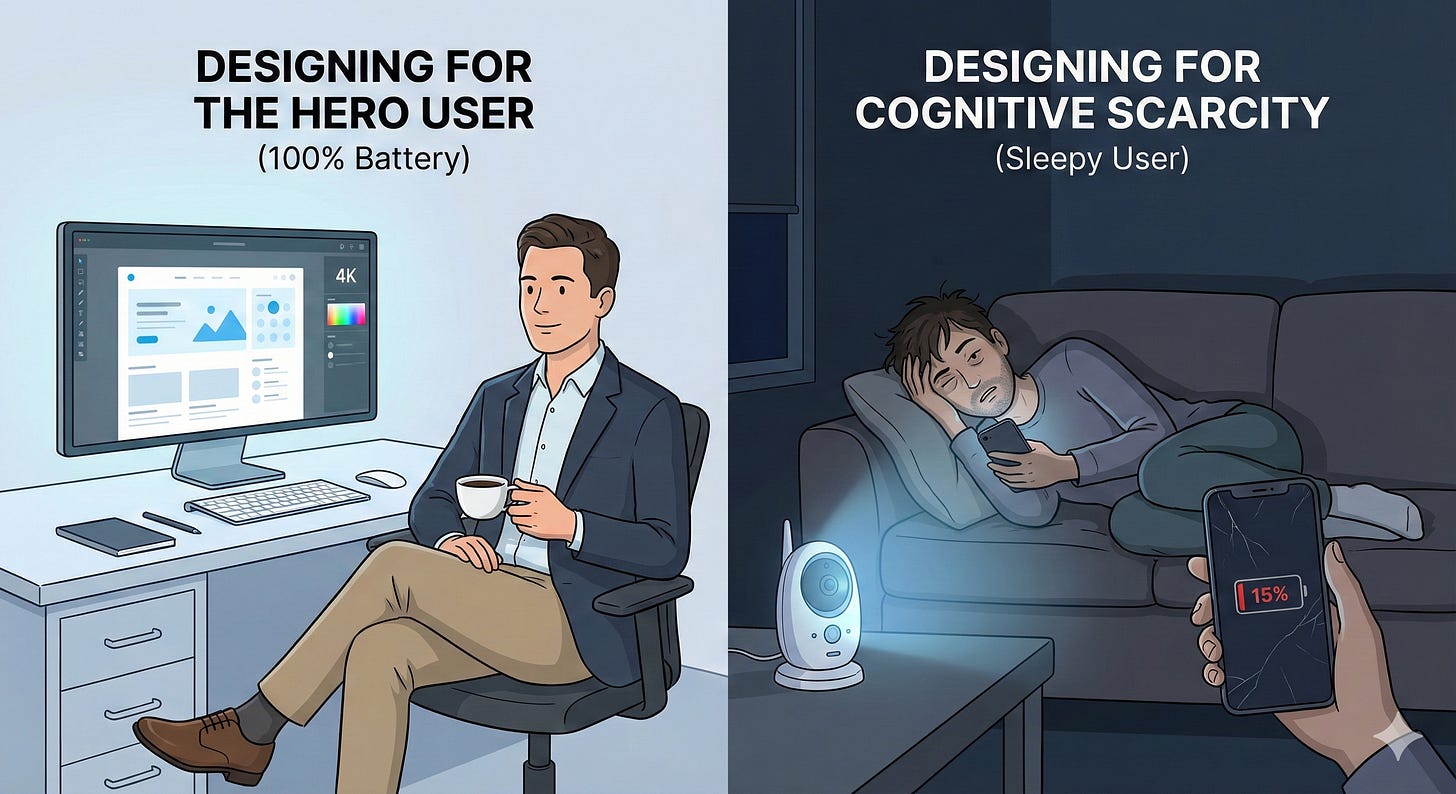

We imagine a “Hero User.” This person is sitting at a well-lit desk with a cup of coffee. They have a stable fiber connection. They are fully rested, emotionally regulated, and reading every line of text they see. We call this the “Happy Path.”

But in the wild, your user is often on the “Sleepy Path.”

They are operating on 15% battery—biologically and technologically. They are scrolling one-handed while holding a crying baby, standing on a crowded train with spotty signal, or trying to pay a bill at 1:00 AM while panicked.

They are in Cognitive Scarcity: a temporary drop in mental bandwidth caused by stress, fatigue, or distraction.

When you design for the Hero User, you build fragility. When you design for the Sleepy User, you build resilience.1

Here is the difference between a Hostile Interface and a Resilient Interface.

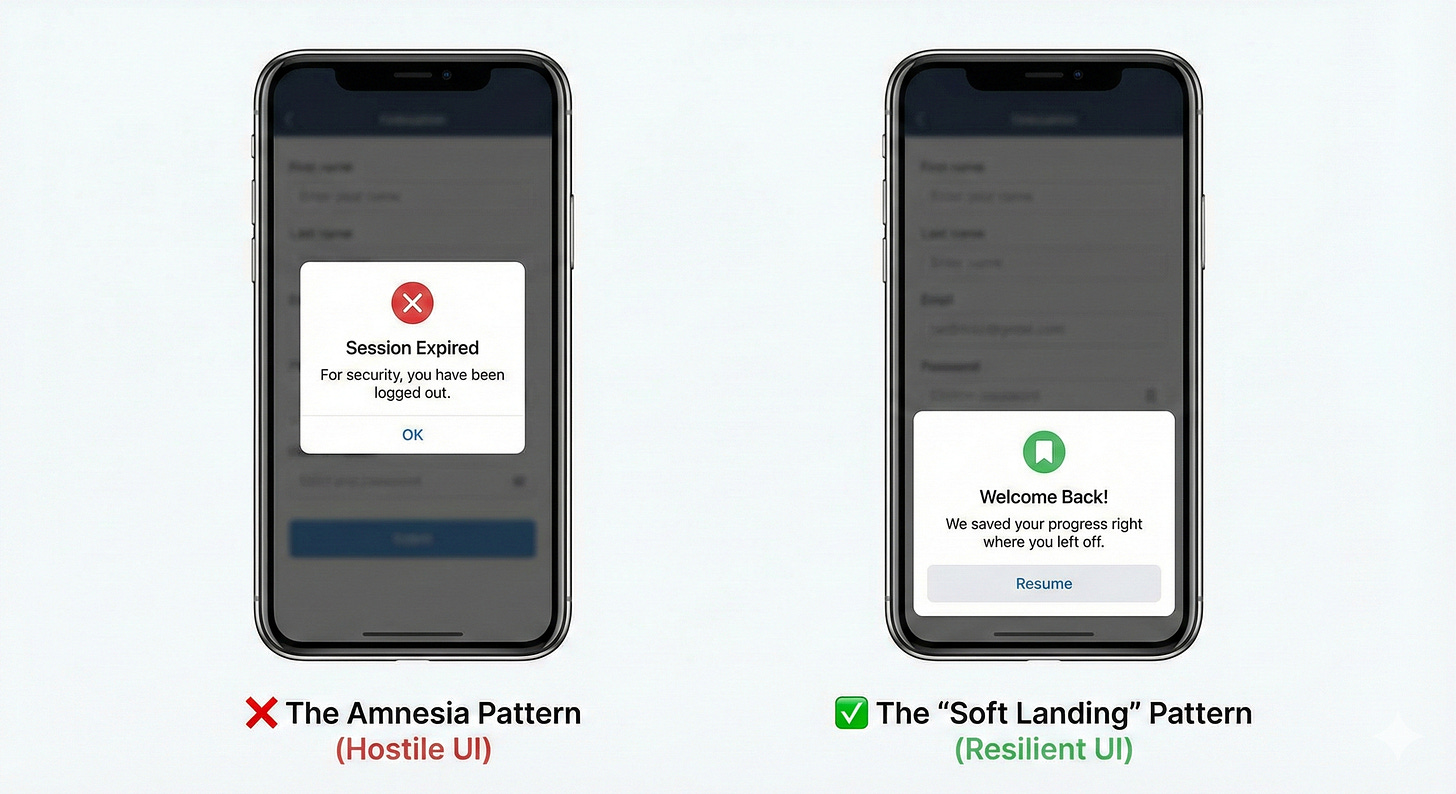

Pattern 1: The Session Timeout

The Concept: Amnesia vs. The Bookmark

The Scenario: A user gets halfway through a complex application (insurance, taxes, housing) but gets distracted by real life. They return 20 minutes later.

❌ The Hostile UI

The standard security pattern prioritizes the database over the human. It assumes the user is a security threat, rather than a busy person.

The Experience: A cold modal stating “Session Expired.” When the user clicks “OK,” they are booted to the login screen. Their data is wiped. They quit.

✅ The Resilient UI

The “Soft Landing” pattern assumes the distraction was involuntary. It offloads the memory burden from the user to the system.

The Experience: A warm modal stating “Welcome back. We saved your progress.” The user enters their password, and the screen restores exactly to the field they were editing.

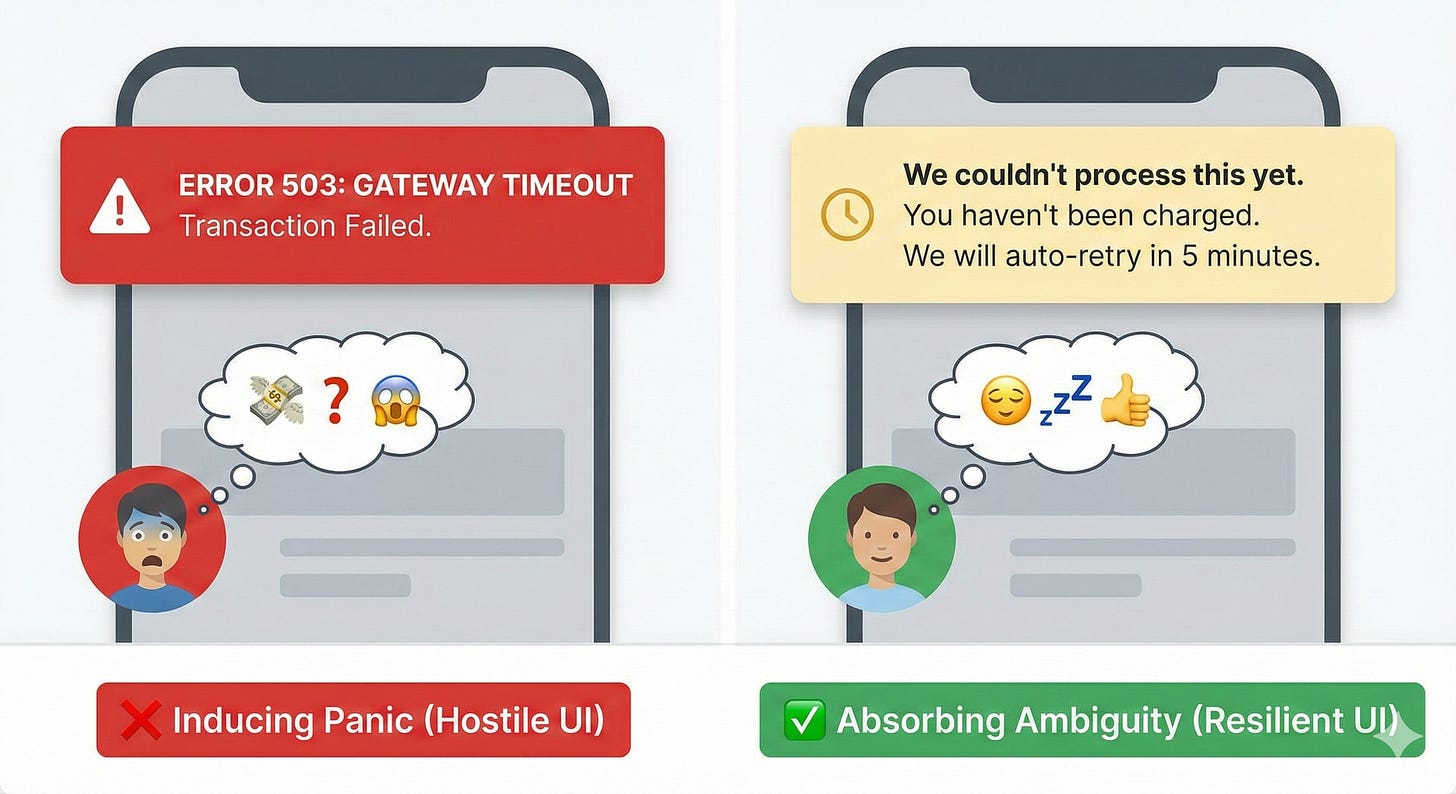

Pattern 2: The Critical Error

The Concept: Panic vs. Assurance

The Scenario: A payment fails or a sync breaks. The system needs to inform the user that a process has stopped.

❌ The Hostile UI

This pattern pushes the cognitive load onto the user. It uses “System-Speak” (Error codes, Gateway Timeouts) that induces panic in non-technical users.

The Experience: A red banner reading “Error 503: Gateway Timeout.”

The User Thinks: “Did I lose my money? If I click it again, will I be charged twice? I don’t have time to call support.”

✅ The Resilient UI

This pattern absorbs the ambiguity. It translates the technical failure into a financial status update.

The Experience: A yellow banner reading “We couldn’t process this yet. Don’t worry, you haven’t been charged. We will auto-retry in 5 minutes.”

The User Thinks: “Okay. My money is safe. I can go to sleep.”

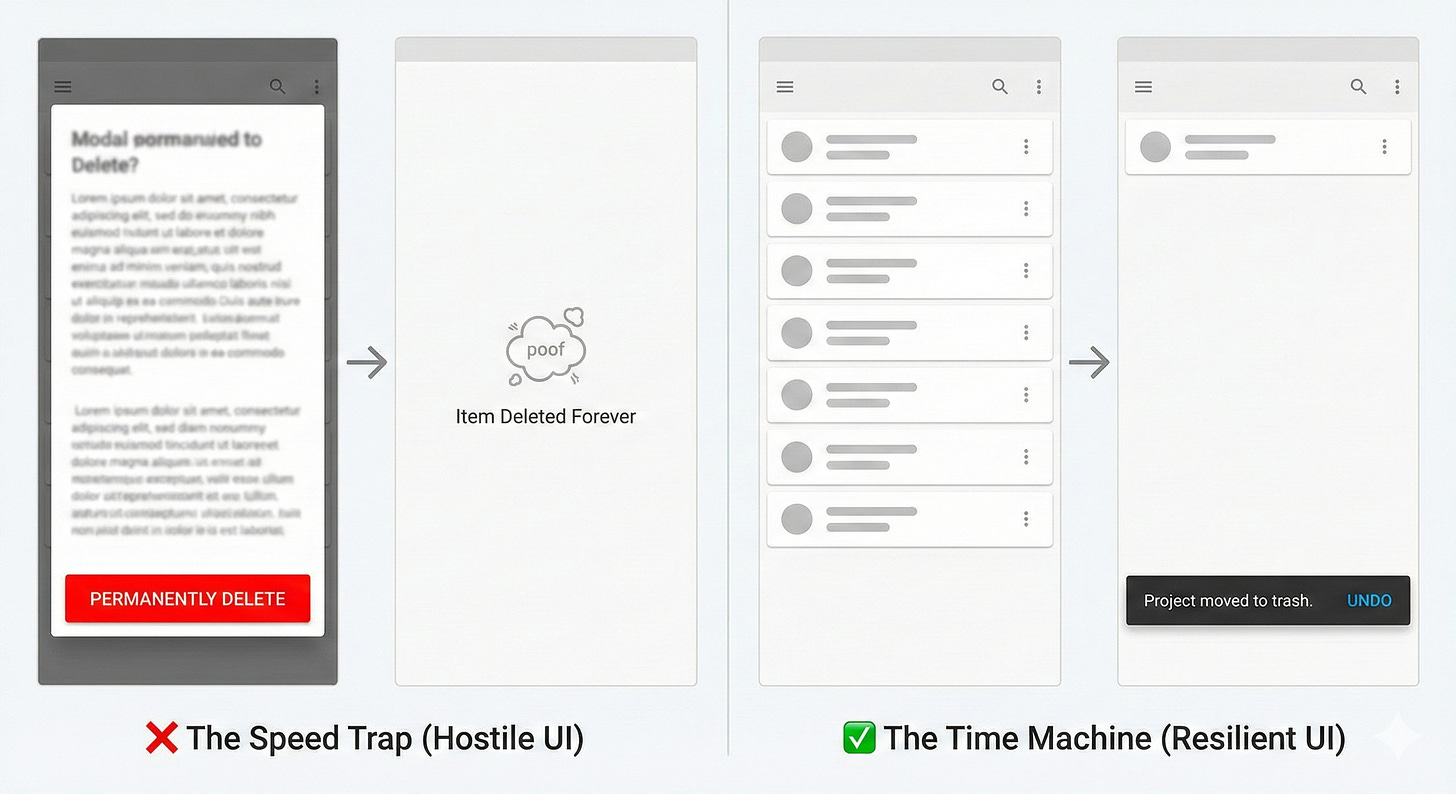

Pattern 3: The Destructive Action

The Concept: Fear vs. Forgiveness

The Scenario: The user hits a button that destroys data (Delete Project, Cancel Subscription, Remove User).

❌ The Hostile UI

This relies on the user reading fine print while rushing. It is a “Speed Trap”—it assumes the user is reading, but the user is scanning.

The Experience: A modal asking “Are you sure? This cannot be undone.”

The Risk: Sleepy users operate on muscle memory. They see a modal, look for the bright red button, and click it before their prefrontal cortex registers the warning.

✅ The Resilient UI

This pattern accepts that “Fat Finger” mistakes happen. It replaces fear with time.

The Experience: The item disappears immediately, but a toast notification appears: “Project moved to Trash. [Undo]”

The Principle: Never demand perfection from a tired person. Always offer a time machine.

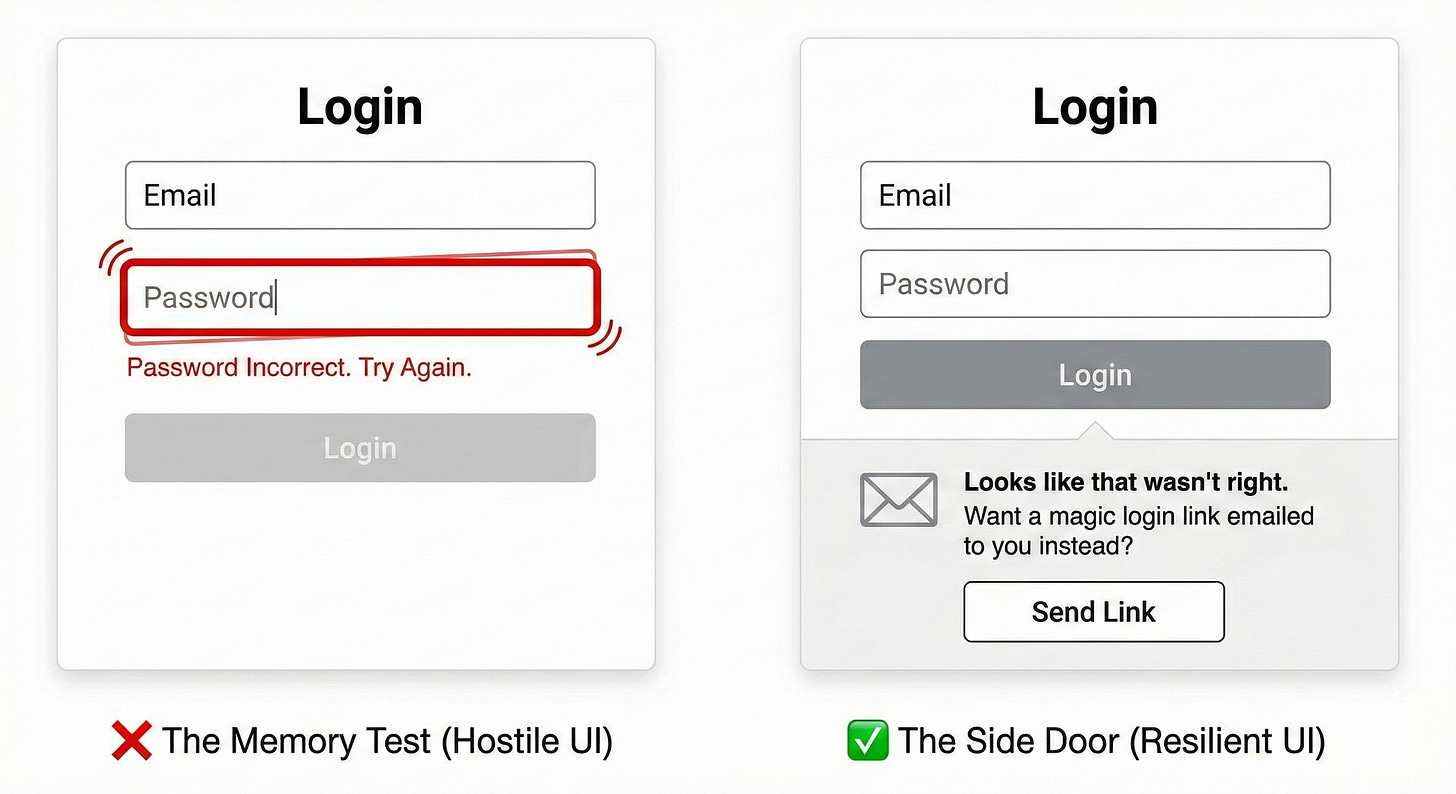

Pattern 4: The Login Loop

The Concept: The Memory Test vs. The Key

The Scenario: The user is trying to log in on a new device but can’t remember their password.

❌ The Hostile UI

The “Memory Test.” It demands high-fidelity recall at the exact moment the user is likely frustrated.

The Experience: A shaking text field saying “Password Incorrect. Try Again.”

The Result: The user tries three variations, gets locked out, and churns.

✅ The Resilient UI

The “Side Door.” If the user fails the primary challenge, the system automatically offers a lower-friction alternative.

The Experience: After one failed attempt, the UI expands: “Looks like that wasn’t right. Want us to email you a login link instead?”

The Principle: Don’t make them bang on the lock. If the front door is stuck, open the window.

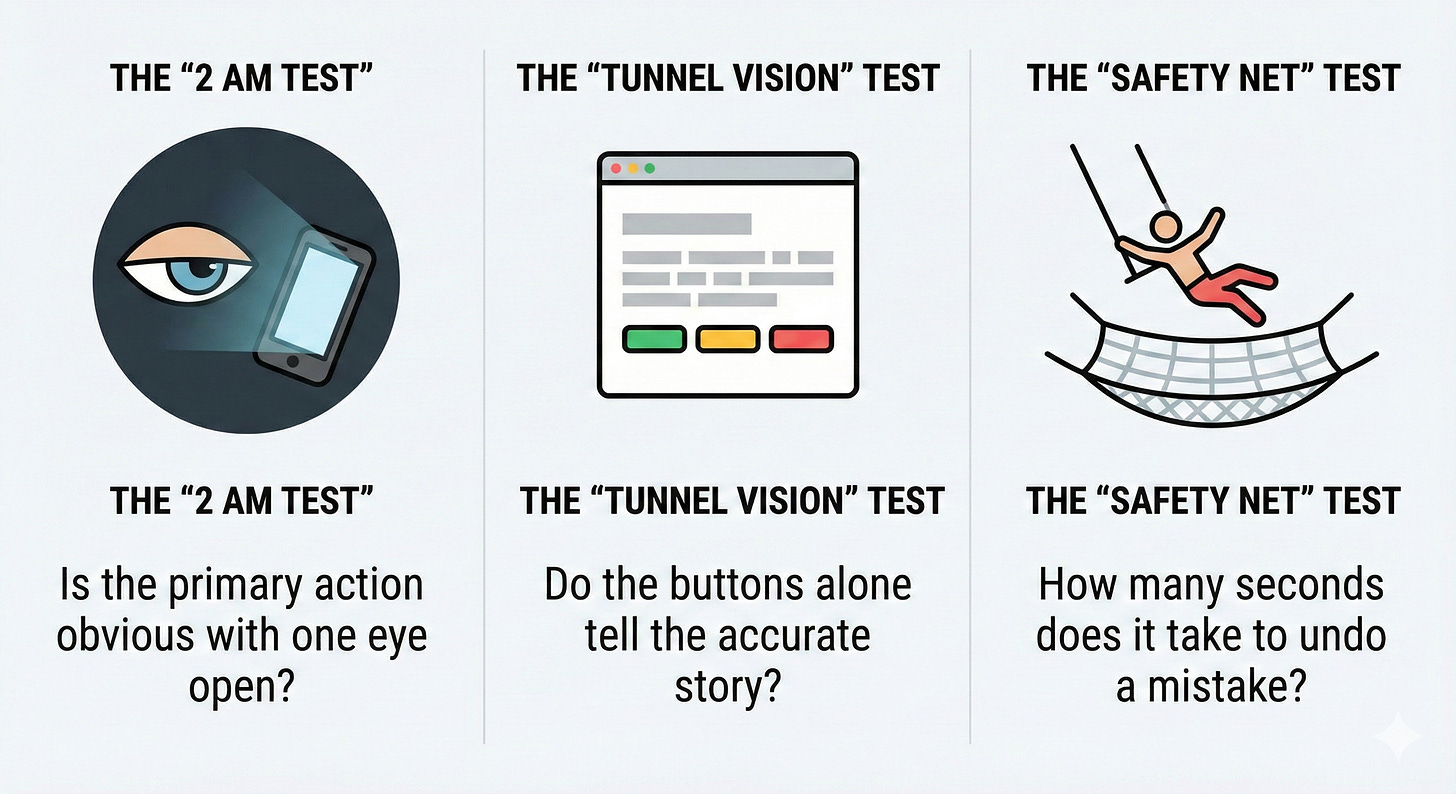

The Designer’s Checklist for Low Energy

Designing for cognitive scarcity isn't about "dumbing down" the interface. It's about respecting your user's biological reality.

When reviewing your flows, stress-test them against these three questions:

The “2 AM Test” If I looked at this screen at 2:00 AM with one eye open, is the primary action obvious? Or do I have to read a paragraph to understand what to do?

The “Tunnel Vision” Test Sleepy users ignore grey text. If I remove all the helper text and subheaders, do the buttons alone still tell the accurate story?

The “Safety Net” Test If I tap the wrong button by accident, how many seconds (and how many clicks) does it take to fix it?

Attention is a finite resource. A respectful UI doesn’t spend it unless it has to.2

This is the digital equivalent of the "curb-cut effect." Just as sidewalk ramps originally specifically designed for wheelchair access incidentally improved mobility for parents with strollers, travelers with rolling luggage, and delivery workers, lowering the cognitive bar for the "2 AM user" raises the overall usability ceiling for everyone. An interface easy enough for an exhausted person is effortless for a rested one.

An evolution of Steve Krug’s foundational maxim, "Don’t make me think." While Krug’s philosophy emphasizes clarity to reduce cognitive load for busy users scanning the page, the "Sleepy User" framework emphasizes resilience to accommodate users whose cognitive capacity is temporarily impaired by biology or circumstance. Krug’s goal is a frictionless "happy path" for a distracted user; the goal here is a safe, recoverable "unhappy path" for an exhausted one.

A cold "Session Expired" modal is actually perfectly usable according to Krug—it’s clear and tells you what happened.

But it fails the "Sleepy User" test because it lacks empathy for why the user stopped interacting.