The Worldview with a Gun

No single ontology—vendor or otherwise—should monopolize state violence.

A worldview shouldn’t have a gun.

We have moved beyond the era where AI merely “informs” decisions. Proprietary ontologies—opaque systems that categorize people as “threats,” “militants,” or “risks”—have ceased to be just analytical tools. Wired into police dispatch, drone tasking, and prison controls, they have become the infrastructure through which state violence flows. These ontologies are not maps; they are rails guiding where violence falls.

Consider Palantir Gotham. The platform goes beyond aggregating warrants or social media; it synthesizes a reality where “impactful targets” literally light up on a screen, waiting for action. It decides whose debts signify risk, whose associates imply complicity, and whose presence on a street corner justifies suspicion. Cities from Los Angeles to Hesse, Germany, feed their databases into Gotham and inherit a vendor’s paranoid worldview under the guise of “visibility.”

For deeper background, see how police use Palantir, coverage of Palantir’s expansion in Germany, and legal analysis of Palantir’s influence in policing.

Axon Fusus extends this logic into real time, merging live camera feeds, drones, license plate readers, and body cameras into a unified surveillance nerve center. Automated alerts nudge officers toward intervention before any human hesitation can take hold. Axon markets Fusus as a “real-time intelligence platform” and infrastructure for “safer corrections,” yet reporting shows how it disproportionately saturates poor neighborhoods with watchful eyes (Gizmodo’s investigation).

In Gaza, the stakes become stark. +972 Magazine’s investigation of Lavender describes an AI system that assigned “militancy” scores between 1 and 100 to tens of thousands of Gazans—mostly men—churning bulk data into kill lists. In parallel, Gospel (Habsora) generated building and infrastructure targets at industrial tempo. Human “review” in this pipeline often amounted to roughly 20 seconds per target, checking only basics like gender and address, with a chilling tolerance for civilian casualties because the machine said target. At this pace, the “human in the loop” is a façade—a latency constraint, not a source of moral agency.

Once deployed, these systems convert ontology from a philosophical concept into the very fabric of violence. It becomes the street grid, the pattern of lives deemed expendable, the logic of what gets bombed first.

To understand its commercial scale, see the private companies quietly building a police state.

Manufacturing killability

These AI systems don’t merely predict risk—they manufacture killability. They distill complex political judgments into scores sold back to the state as objective truths.

In Gaza, this means mass surveillance turning into daily death lists, with officers instructed to treat these outputs “as if they were human decisions” (see the Lieber Institute’s symposium).

In the United States, prisons use Securus to eavesdrop on millions of calls, stripping context from slang, code-switching, and emotional venting to flag “imminent threats.” Investigations describe how AI systems now monitor communications in real time to forecast crimes (KSBY report, MIT Technology Review). The people subjected to this processing have no meaningful way to opt out.

On a more everyday level, tools like COMPAS label Black defendants as “high risk” at roughly double the rate of white defendants who did not reoffend, turning structural racism into mathematical fact. Chicago’s Strategic Subject List transforms histories of over-policing in Black and Latino communities into heat maps justifying intensified patrols for people who may have no violent record at all (legal critiques).

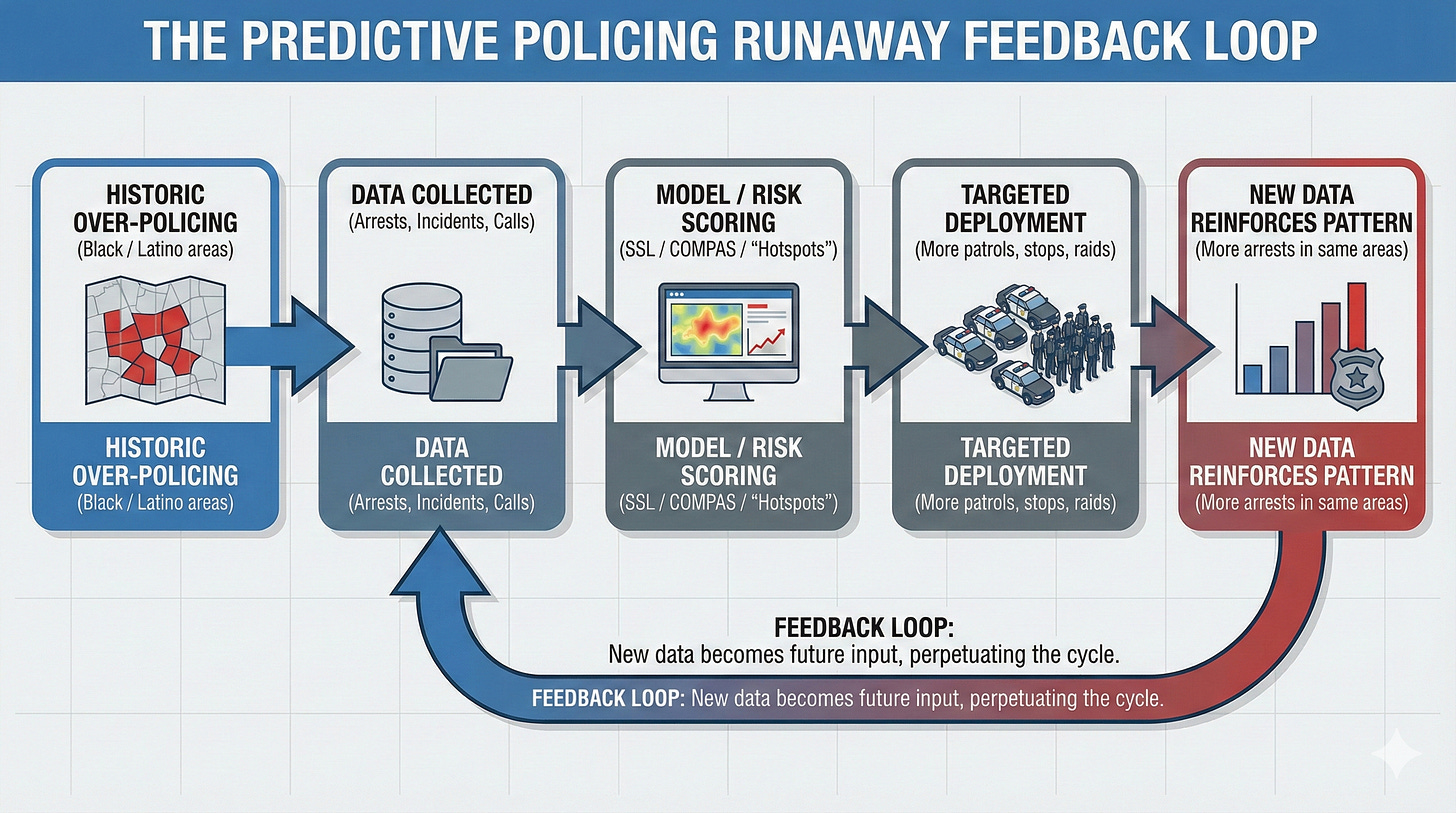

This is epistemic laundering: the state targets a population; the population generates data; the model trains on that data and tells the state, you were right to target them. Responsibility blurs and shifts from policymakers to “the system.” Whether the vendor is Palantir or an open-source engineer matters less than the fact that one ontology has been given the exclusive right to define who counts as dangerous. That is a monopoly over killability.

The feedback loop

Once the loop closes, the prophecy fulfills itself.

Police flood a “high-risk” zone. They make more arrests. The database logs the arrests and marks the area as even higher risk. More patrols follow. In Chicago, this was not a surprising side effect; it was how the Strategic Subject List and related systems were designed to operate.

Proprietary complexity makes this almost impossible to contest. What counts as a “gang indicator”? Which unpaid bill signals risk? Those definitions sit behind trade secrecy and NDAs. Securus converts slang into evidence; COMPAS turns structural racism into a risk score; Lavender can turn mere phone proximity into a death sentence. The nuance of why the data looks the way it does—poverty, segregation, coercion, colonial policy—vanishes. All that remains is the line: “The system found a pattern.”

Marketing language tidies up the rest. “Turnkey.” “Frictionless.” “Real-time.” Gotham promises seamlessness; Fusus sells speed. But friction is another word for due process. Seamlessness is simply the absence of oversight.

What these systems actually do is convert raw political fear—of crime, of terror, of the poor—into dashboard objectivity. Foucault’s “delinquent” is no longer just a subject described in a report; he is a data object, auto-generated and continuously updated.

For one legal-theoretical frame on this, see Artificial Intelligence Law through the Lens of Michel Foucault.

Langdon Winner warned that artifacts have politics. These dashboards are artifacts built to centralize power and treat those on the margins as noise. The faster they run, the more anything that doesn’t fit—duress, context, care—gets thrown away as “unstructured” data. The human loop shrinks. The appeal channel evaporates. Violence becomes automatic.

The false promise of the “good guy with an ontology”

One common response goes like this: We’re not against AI or analytics. We just need better data, better models, a more ethical vendor.

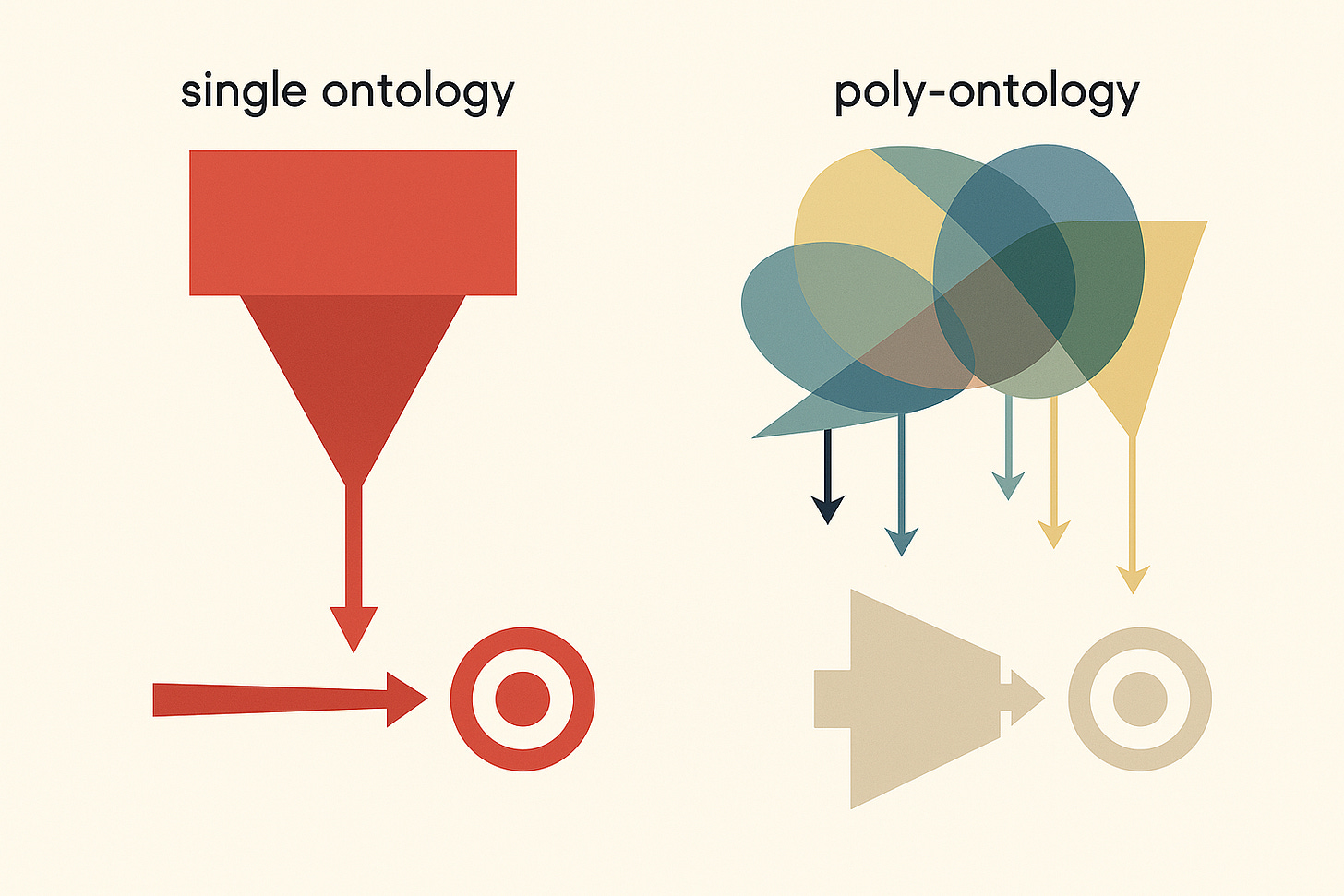

That line misses the point. The problem is not only which ontology is in charge, but that any single ontology is allowed to monopolize the path from data to force.

Even a “good” stack, run by well-meaning people, consolidates enormous power over what counts as threat, what counts as order, and whose life is treated as collateral. It replaces contestation with configuration. It narrows the field of possible futures to those compatible with one model’s worldview.

“Good guy” ethics, layered on top of unchallenged architecture, become a fig leaf. Innovation is celebrated; veto power is not. And a handful of technical elites end up acting as de facto legislators over life and death, without ever being named as such.

Break the monopoly

No single schema—state, vendor, or military—should ever be the sole map for the guns.

Chicago’s stalled consent decree shows how little leverage traditional oversight has over a force increasingly governed by black-box systems; oversight reporting has already documented how Chicago police failed to meet even basic reporting goals. Gaza shows what happens when a singular ontology is fused at scale to munitions and treated as “precision.”

Breaking this monopoly is not a matter of better messaging; it is structural work. It looks like:

Banning turnkey pipelines that allow a single system to run data through one lens straight into lethal or carceral action.

Imposing legal ceilings on automated tempo so that systems cannot outpace the possibility of human veto.

Embedding poly-ontologies—competing legal, historical, community, and adversarial perspectives—into every chain from database to trigger, with real power to say “no.”

As I argue in “The In-House Ethicist”, formal boards and principles without structural veto power only enable co-optation. You cannot sprinkle ethics on top of a machine whose core function is to move faster than dissent.

Worldviews will always carve up reality. Guns, for now, are not going away. But the decision to fuse one proprietary hallucination to the trigger, the cage, and the drone is a choice. That choice can—and must—be refused.

That refusal is the core of Ethotechnics: designing systems so that inference never rules alone over force, and so that no single worldview is ever given a monopoly over who is allowed to live.