The Pyrrhic Condition

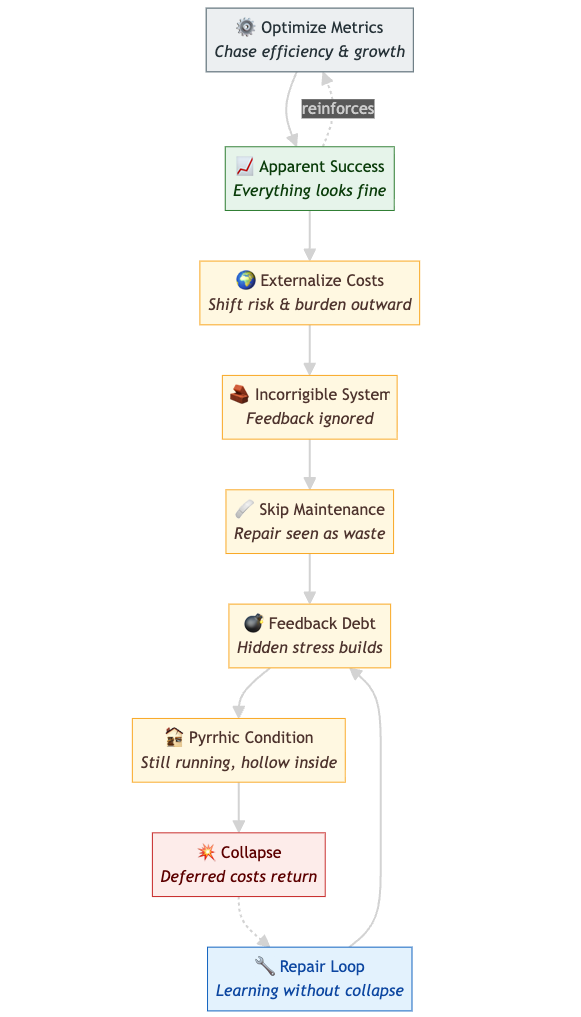

Hospitals, platforms, universities, and economies all improve the metrics that define success while quietly eroding the conditions that make those metrics meaningful.

Everything works until it doesn’t; hospitals set records for throughput, platforms break engagement highs, and the economy keeps expanding. By every metric, things are fine. Yet each success feels thinner than the last. Engagement rises as trust collapses. Unit costs fall as resilience erodes. Dashboards glow green while the foundations crack.

This is the failure pattern of our age: systems that perfect their performance while hollowing out their purpose. Most systems fail not by stopping, but by continuing to work long after it makes sense. As Ivan Illich warned, institutions become counterproductive when they become the institutional embodiment of their own purpose. Hospitals that make people sick, platforms that isolate—each reveals what happens when function outlives sense.

I call this the Pyrrhic condition: a system that survives by exhausting its reason to exist. It wins every battle, only to lose the war of meaning. What begins as an adaptive strategy, as Joseph Tainter noted, hardens into a maintenance burden that consumes its host.

The system’s primary mechanism is externalization. This is more than a market flaw; it is how an order sustains its self-image. Economist Herman Daly described the economy as a wholly owned subsidiary of the environment. This remains true but incomplete. The system’s logic relies on a geography of elsewhere—colonies, peripheries, racialized labor, and ecosystems cast as empty.

What looks like universal reason is built on selective blindness. As philosopher Sylvia Wynter put it,

“the struggle of our new millennium will be one between the ongoing imperative of securing the well-being of our present ethnoclass (i.e., Western bourgeois) conception of the human, Man, which overrepresents itself as if it were the human itself, and that of securing the well-being, and therefore the full cognitive and behavioral autonomy of the human species itself/ourselves.” - Sylvia Wynter

To export its costs, the system must become deaf to the signals of harm. This creates the second mechanism: incorrigibility.

Incorrigibility is feedback without learning. The system becomes information-saturated but correction-proof. Dashboards, surveys, and listening sessions proliferate, yet they function ceremonially, metabolizing contradiction as reassurance. Critique does not threaten the system; it becomes a maintenance function. The system survives by feeding on its own dissection, equating feedback with threat and redesign with defeat. In physics, brittleness precedes fracture; in ethics, incorrigibility precedes atrocity.

The material result of this epistemic failure is maintenance denied. Maintenance—the work of alignment, upkeep, and repair—exposes the very costs the system is designed to hide. It is interpreted as weakness, a drag on performance. Because it does not scale, pitch, or publish well, maintenance is the first budget cut and the last prestige.

Stress doesn’t vanish; it migrates until it breaks something or someone quieter. Who patches the world, and who runs it until it breaks—that is the hidden architecture of modern life.

When the feedback debt becomes unpayable, the system implodes. Collapse can be reduced to bookkeeping: the moment when off-ledger costs re-enter the ledger as financial loss, ecological shock, or civic distrust. From inside the system, it appears abrupt and moralistic, a drama of “bad actors.” From the margins, it looks mechanical and inevitable.

The crucial design question isn’t who to blame, but why feedback was forced to arrive in the form of crisis.

If there’s an alternative, it may lie in what AI researchers call corrigibility: the capacity to accept correction without paralysis. But even this language can be captured. Every empire of reason calls its reforms humility. Corrigibility risks becoming just another protocol for surviving contradiction without changing direction. The goal must be to stop mistaking correction for continuation, not simply to make systems “correctable.”

The obstacle isn’t coordination itself, but its scale. Planetary management imagines a single system steering the world as an object—a word built on separation, boundary, and mastery.

Living grammars of endurance, like Māori kaitiakitanga or Andean ayni, are not “alternative systems.” They are practices that refuse the fiction that feedback can be separated from obligation.

As systems centralize, they narrow the channels through which experience is legible. Some worlds become insensible so that others can measure. A world that coordinates too tightly burns through the slack that keeps it alive.

What’s needed are federations of repair, replacing top-down models of control. The aim is reciprocal awareness, rather than seamless integration.

All closed systems drift toward Pyrrhic states. Success hardens, feedback narrows, denial sets in. Unless work is done to keep them open, virtue itself decays into performance. That work—maintenance, correction, repair—is what keeps meaning from collapsing into momentum.

We don’t need systems that listen better; we need ones willing to stop, to relinquish the illusion that continuation is proof of life.