The Festival and Non-Festival Divide

A False Narrative of Impossibility

Festivals like Burning Man, Sustain-Release, Coachella, and even wellness retreats or TED conferences represent a growing phenomenon in modern life, where individuals temporarily step outside the constraints of capitalist, consumerist society and experience a fleeting sense of radical freedom. These spaces offer glimpses of what alternative, utopian communities might look like, operating on principles of gifting, community, self-expression, and anti-hierarchical living. However, once these events end, participants return to their regular lives, shaped by the structures of hierarchy, individualism, and competition.

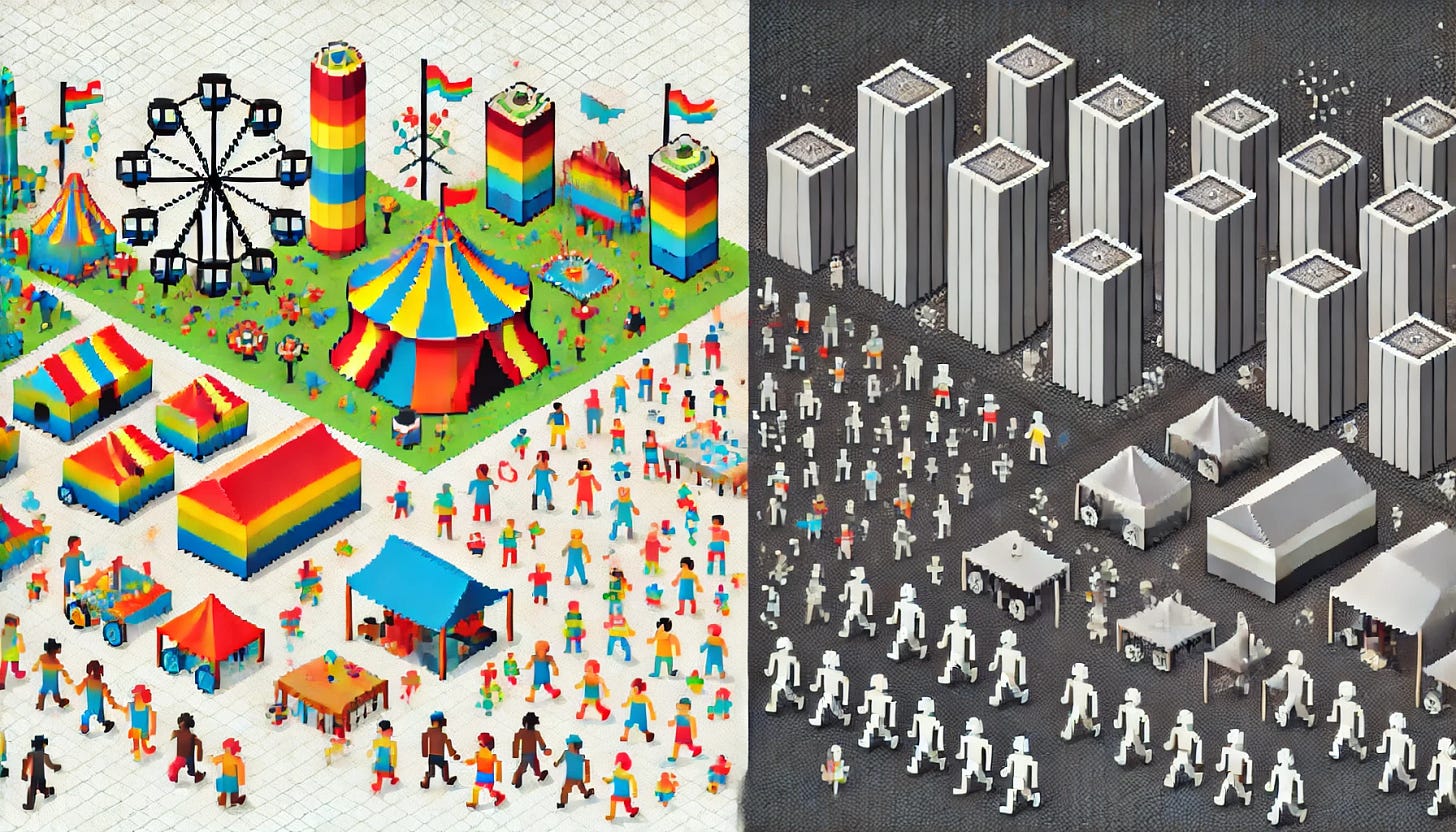

This creates a divide between the festival world and the non-festival world, and between the festival self and the non-festival self, a divide that perpetuates a false, convenient narrative of impossibility. This narrative serves to compartmentalize radical experiences, framing them as temporary indulgences rather than sustained, transformative ways of living.

The Festival World: Temporary Utopias

Festivals like Burning Man are constructed as prefigurative spaces, temporary utopias where participants can live out radical ideals of communal living, gifting economies, and non-hierarchical relationships. For the duration of the event, participants experience a world that feels radically different from the non-festival world—a world where individuals are encouraged to express themselves freely, to form communities based on trust and collaboration, and to break away from the constraints of capitalism and consumerism.

By breaking the festival/non-festival divide, we can begin to challenge the structures that govern our everyday existence, turning the fleeting utopias of festivals into sustained movements for social transformation.

However, the very temporality of these festivals undermines the radical potential they claim to represent. These events are explicitly designed to be temporary, with participants building these utopian worlds, living in them for a week or a weekend, and then meticulously dismantling them at the event’s end. The ritual of constructing and then dismantling these spaces each year reinforces the idea that these alternative ways of living are exceptional—brief moments of escape from the "real world" that cannot be sustained outside of the festival environment.

The temporary nature of these utopias creates a psychological divide in the minds of participants, conditioning them to believe that the radical values they experienced are only viable within the confines of the festival. This dynamic creates what I will call the festival/non-festival divide, a conceptual and psychological separation between the behaviors, values, and ideals experienced during the festival and those deemed acceptable or practical in the broader world.

The Non-Festival World: Reinforcing a False Narrative of Impossibility

The non-festival world is the reality that participants return to after the festival ends—the capitalist, hierarchical, and consumerist structures that govern everyday life. In this world, participants are expected to prioritize individualism, productivity, and competition. The values of gifting, radical inclusion, and communal living, which were celebrated in the festival environment, are often seen as impractical or idealistic within the context of the non-festival world.

This transition back to the non-festival world reinforces a false narrative of impossibility—the belief that the radical experiences and values of the festival are inherently unsustainable in everyday life. This narrative is convenient for both participants and the broader system because it allows individuals to indulge in utopian ideals temporarily without ever challenging the deeper systems of power, capitalism, and hierarchy that govern their lives outside the festival.

The narrative of impossibility becomes a thought-terminating cliché, much like the phrase "that's just how the world works." It provides an easy, convenient explanation for why the festival self—its radical behaviors and values—must be contained within the temporary, curated environment of the festival. It discourages participants from questioning whether the festival’s values can be applied to their work, relationships, or communities in the non-festival world, allowing them to comfortably return to the systems of power and hierarchy they briefly escaped.

The Festival Self and the Non-Festival Self: A Fragmented Identity

The festival/non-festival divide also manifests as a division between the festival self and the non-festival self. During the festival, participants may embody a version of themselves that is open, creative, generous, and connected to community.

They may experiment with radical self-expression, engage in gifting economies, and form relationships based on equality and inclusion. This version of the self feels liberated, free from the constraints of the capitalist, consumerist structures that govern everyday life.

However, once the festival ends, participants must reintegrate into the non-festival world, where the expectations of economic productivity, social hierarchy, and normative behavior are re-applied. The non-festival self is conditioned by these structures, which often feel incompatible with the radical potential experienced at the festival. This creates a fragmentation in identity, where participants feel that they are two different people depending on whether they are in the festival or non-festival world.

This fragmentation leads to a sense of alienation from the festival self, as participants come to believe that their festival behaviors and values belong only within the controlled, temporary environment of the festival. Over time, this dynamic can create a kind of double consciousness, where participants are aware of the disconnect between their festival self and their non-festival self, but feel powerless to reconcile the two.

The Infantilization of Radical Experience

The infantilization of radical experiences at festivals further reinforces the narrative of impossibility. Festivals, by design, allow participants to explore values like communal living, gifting economies, and anti-hierarchical relationships in a playful, experimental space. However, this space is explicitly temporary, and the behaviors it encourages are often framed as childlike indulgences—something to be experienced briefly, but not carried into "adult" responsibilities in the real world.

This infantilization leads participants to internalize the belief that the radical potential they experience at festivals is not serious or practical enough to exist outside the curated environment of the event. They learn to treat these radical behaviors as part of a fantasy world that can only exist in carefully controlled, short-term settings.

The narrative of impossibility is thus reinforced by the very structure of the festival, which encourages participants to view their festival selves as immature, temporary versions of themselves, rather than something that could be integrated into their broader lives.

The Commodification of Radical Experience

In addition to the temporal and spatial limitations of festivals, the commodification of radical experiences also plays a critical role in perpetuating the narrative of impossibility. Festivals like Burning Man may promote values of decommodification, but they are often commodified experiences themselves. Tickets are sold, camps require resources that are inaccessible to many, and the festival’s infrastructure is built on participants bringing in their own wealth and labor. Even the aesthetics of the festival—the art, fashion, and social dynamics—are now marketed as products in mainstream culture.

This commodification dilutes the radical potential of the festival, turning it into a spectacle of resistance that ultimately reinforces the status quo. While participants may feel they are engaging in acts of resistance or self-expression, the festival becomes a curated space where radicalism is safely contained. The festival becomes a form of controlled opposition, where participants can experience a brief glimpse of freedom, but without challenging the broader systems of power and hierarchy that govern their lives.

The False Convenience of Impossibility

The narrative of impossibility is convenient because it allows participants to experience radical potential without feeling responsible for carrying it forward into their everyday lives. It provides a psychological escape, allowing individuals to live out radical behaviors for a short time, but without having to engage in the hard, systemic work of transforming the non-festival world.

The narrative of impossibility becomes a form of moral license, where participants feel righteous for having experienced a better world, but without feeling obligated to challenge the structures of inequality and consumerism that define their broader existence.

This psychological convenience explains why participants may dismiss attempts to bring festival values into the real world as naive or unrealistic. Having internalized the belief that the festival’s radical potential is inherently fragile, participants react defensively when confronted with the idea that these values could be sustained beyond the event.

The narrative of impossibility has trained them to see the festival as a fantasy space, and any attempts to integrate its values into the real world are often dismissed as idealistic or impractical.

Breaking the Narrative: The Challenge of Integration

To break free from this false, convenient narrative of impossibility, participants must confront the compartmentalization of their festival selves and the structures that reinforce it. This means rejecting the idea that the values of the festival belong only within the curated, temporary space of the event. Instead, participants must work to integrate the radical potential they experience at festivals into their everyday lives, challenging the systems of hierarchy, consumerism, and individualism that govern the non-festival world.

This process of integration requires participants to confront the contradictions between the festival world and the non-festival world, and to find ways to live out the values of community, gifting, and radical self-expression in spaces that are not designed for them. It involves recognizing that the narrative of impossibility is not inherent to the non-festival world—it is a convenient construct designed to protect the status quo.

Rejecting the Convenient Fiction

Ultimately, the narrative of impossibility that festivals perpetuate is a convenient fiction—one that allows participants to experience radical potential temporarily without feeling responsible for carrying it forward into their broader lives. This narrative protects both the participants and the system from the discomfort of systemic change, allowing individuals to compartmentalize their festival selves as fleeting indulgences rather than sustained, transformative identities.

To challenge this narrative, participants must reject the false convenience it offers and embrace the difficult work of integrating their radical values into their continuous lives. By breaking the festival/non-festival divide individuals can begin to challenge the structures that govern their everyday existence, turning the fleeting utopias of festivals into sustained movements for social transformation.

Main Character Energy is Good Again

The comparison between the viral responses to the Kaytranada Boiler Room dancer, who was ridiculed, and the dancer at Swami Sound's boat set, who was celebrated, highlights a significant shift in societal attitudes toward public displays of joy.