Abolishing The Classics and Cultural Imperialism

Understanding why Classics departments got funded helps us clarify their irredeemability

The study of The Classics—the literature, philosophy, and history of ancient Greece and Rome—has long held a privileged position within Western education. This elevation is often framed as a neutral and natural process, reflecting the intrinsic value of these ancient texts in shaping the intellectual traditions of the West.

However, closer examination reveals a more deliberate effort to use The Classics as tools for reinforcing Western dominance. Their canonization is not merely an academic process, but part of a broader project of cultural imperialism, aimed at asserting and maintaining Eurocentric power. Wealthy philanthropists, elite educational institutions, and colonial governments have all played roles in constructing and sustaining this intellectual framework, using The Classics as ideological instruments to legitimize Western superiority.

The continued centrality of The Classics in education is thus intertwined with colonial histories and imperial strategies, suggesting that their study is part of a broader project to preserve Western cultural hegemony.

The Manufactured Canonization of The Classics: A Deliberate Project

The perception that The Classics are the cornerstone of intellectual life is a deliberate construction, designed to reinforce Western values and marginalize alternative perspectives. During the 19th and early 20th centuries, wealthy industrialists and philanthropists, such as Andrew Carnegie, John D. Rockefeller, and the Mellon family, invested heavily in classical studies at elite universities. These investments were not random acts of charity, but calculated moves to ensure that the intellectual traditions of Western civilization remained dominant in academic discourse and broader society.

The study of The Classics reinforced the belief that Western civilization’s success was due to its superior intellectual heritage, rather than the violent exploitation of colonized peoples and resources.

The financial support for classical studies provided these philanthropists with a way to legitimize their own power. By promoting ancient Greece and Rome as the intellectual forebears of modern Western civilization, they reinforced the idea that Western culture and values were the apex of human development. This, in turn, helped justify the continued dominance of Western empires, whose colonial and imperial ambitions were often framed as efforts to “civilize” non-Western peoples in the same way that Rome had "civilized" the Mediterranean world.

At the same time, this canonization of The Classics marginalized non-Western intellectual traditions. By centering ancient Greece and Rome as the foundation of intellectual progress, these funders and institutions erased the contributions of African, Asian, Indigenous, and other marginalized cultures, perpetuating a Eurocentric narrative of history and civilization. The myth of the superiority of Western civilization, built on the supposed universality of classical texts, became a central tenet of Western education, shaping the worldview of generations of students and leaders.

The Classics as Tools of Imperial Ideology

The relationship between The Classics and imperialism goes beyond the funding of classical studies by Western elites. The texts of ancient Greece and Rome themselves were often used as ideological tools to justify and legitimize Western imperialism. Throughout the 19th century, as European powers expanded their empires across Africa, Asia, and the Americas, they frequently invoked the legacy of ancient Rome to frame their imperial projects as noble and necessary endeavors. The British Empire, in particular, drew parallels between its own expansion and the Roman Empire’s “civilizing mission.”

British colonial officials and intellectuals viewed themselves as the modern heirs to Rome, bringing order, governance, and civilization to the “barbaric” parts of the world. This narrative relied heavily on classical texts, such as those of Cicero, Tacitus, and Virgil, which glorified the Roman Empire’s conquests and governance. By positioning their empire as a continuation of the Roman project, British imperialists could frame colonialism as an enlightened mission, rather than a violent and exploitative enterprise.

This ideological framework was reinforced in the educational systems of the colonies. In British India, for example, the colonial government established schools and universities that closely followed the British model, emphasizing the study of The Classics alongside English literature and history. Figures like Thomas Babington Macaulay, in his 1835 Minute on Education, explicitly argued that the purpose of education in India was to create “a class of persons Indian in blood and color, but English in taste, in opinions, in morals, and in intellect.” By imposing a classical education on colonized populations, the British sought to cultivate a Westernized elite that would help administer the empire while reinforcing Western values.

Colonial Education and the Imposition of The Classics

The imposition of The Classics on colonized populations was not unique to British India. Throughout the British, French, and other European empires, classical education was introduced to local elites as part of a broader effort to control and reshape colonial societies. Colonial schools in Africa, Southeast Asia, and the Caribbean often emphasized the study of Latin, Greek, and European literature, while suppressing indigenous languages, histories, and intellectual traditions. This approach to education was designed to create a class of Western-educated administrators who could help govern the colonies in accordance with European ideals.

In many cases, the study of The Classics was framed as a way to “civilize” the colonized. Just as the Romans had “civilized” the peoples they conquered, so too were the British, French, and other European powers claiming to bring enlightenment to their colonies. Classical education, then, was not simply about intellectual development—it was part of a larger cultural imperialist project that sought to reshape the identities and values of colonized peoples to align with Western norms.

In French colonial Algeria, for example, colonial schools promoted French and classical education while actively suppressing local cultures, languages, and intellectual systems. Indigenous knowledge was devalued or erased entirely, as colonial administrators sought to remake Algerian society in the image of France. Similar patterns can be seen in other colonies, where classical education was used to assert the cultural superiority of the colonizers and undermine local intellectual traditions.

The Role of Wealthy Philanthropists: Reinforcing Western Cultural Hegemony

While colonial governments played a key role in imposing The Classics on colonized populations, wealthy philanthropists and industrialists in the West were instrumental in promoting classical education at home and abroad. Figures like Andrew Carnegie and John D. Rockefeller funded classical studies at universities not only to promote the humanities but to reinforce the idea that Western civilization was the pinnacle of human achievement.

These philanthropic investments were often aligned with broader capitalist and imperialist goals. By funding classical studies, these industrialists helped create an intellectual framework that legitimized Western economic and cultural dominance. The study of The Classics reinforced the belief that Western civilization’s success was due to its superior intellectual heritage, rather than the violent exploitation of colonized peoples and resources.

The influence of these philanthropists can still be seen today. Universities like Harvard, Yale, Oxford, and Cambridge continue to receive significant financial support for classical studies, ensuring that the Western intellectual tradition remains at the center of academic discourse. This support is not simply about preserving knowledge—it is about maintaining a system that privileges Western intellectual traditions over all others, reinforcing the legacy of imperialism and marginalizing non-Western voices.

Intellectual Gatekeepers and the Legacy of The Classics

The deliberate elevation of The Classics has also given rise to a class of intellectual gatekeepers—public intellectuals who perpetuate Eurocentric narratives under the guise of objective analysis.

Figures like Steven Pinker, Nassim Nicholas Taleb, Yuval Noah Harari, and Francis Fukuyama represent the modern heirs of this intellectual tradition, each drawing on classical and Enlightenment ideas to frame their arguments about human progress, history, and the future.

Steven Pinker relies on Enlightenment ideals of reason, science, and progress to argue that Western rationalism is the driving force behind human advancement. His work minimizes the darker legacies of colonialism and exploitation that have contributed to Western dominance.

Nassim Nicholas Taleb draws heavily on Greco-Roman philosophy, particularly Stoicism, to craft his ideas on risk and resilience. By presenting these Western ideas as universal truths, Taleb overlooks non-Western intellectual traditions that offer alternative frameworks for understanding risk and uncertainty.

Yuval Noah Harari’s grand historical narratives in Sapiens and Homo Deus position Western capitalism and technological progress as the inevitable culmination of human development, reinforcing the idea that Western civilization is the apex of human achievement.

Francis Fukuyama’s argument in The End of History and the Last Man—that Western liberal democracy represents the final stage of human political evolution—is deeply rooted in the classical tradition of teleological history, which positions Western political systems as the ultimate expression of human development.

These thinkers are not simply the products of their own intellectual merit. They are part of a broader system that has deliberately elevated Western thought as the standard for intellectual inquiry, ensuring that certain voices—those who reinforce the narrative of Western superiority—are amplified, while alternative perspectives are marginalized.

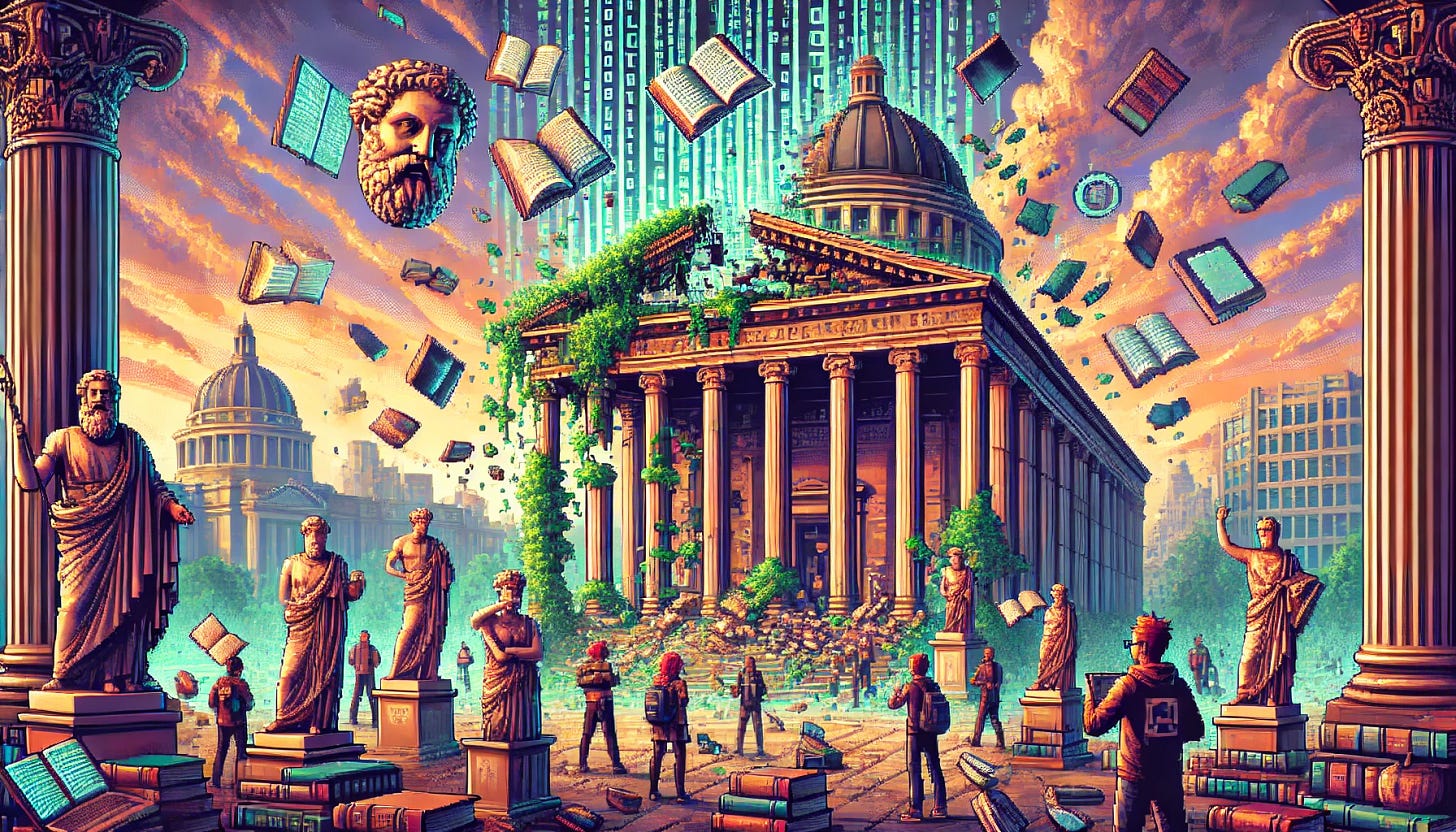

Abolishing The Classics to Dismantle Cultural Imperialism

The canonization of The Classics is not a neutral or organic process but a deliberate strategy to maintain Western cultural and intellectual dominance. The study of ancient Greece and Rome has been used to justify imperialism, shape colonial education, and promote a Eurocentric worldview that continues to marginalize non-Western perspectives. Wealthy philanthropists, elite universities, and colonial governments have all played roles in constructing and sustaining this intellectual framework, using The Classics as ideological tools to reinforce Western superiority.

To break free from this legacy of cultural imperialism, it is not enough to reform the study of The Classics. Abolition is necessary. By dismantling the privileged status of The Classics in education and redirecting resources toward more inclusive and diverse intellectual traditions, we can begin to create a more equitable and just intellectual landscape—one that values the contributions of all cultures, rather than privileging a select few.

The continued centrality of The Classics in education perpetuates a narrow and exclusionary view of human history and progress. Abolishing The Classics as a central discipline would not erase their historical significance but would free up the intellectual and financial resources necessary to elevate the voices and perspectives that have been systematically marginalized.