The Autistic Tendency to Disappear

We keep witnessing departures that resist easy explanation:

A scholar abandons academia for manual labor.

A decorated figure retreats from public life.

A writer, at the peak of their influence, falls into silence.

We often frame these exits as tragedies, regressions, or evidence of psychological collapse. We ask what went wrong.

But what if nothing did—at least not in the way we assume?

What if, instead, these disappearances represent acts of discernment—quiet, deliberate decisions to step away from roles that have become unsustainable?

What if disappearing is not a breakdown, but a refusal to keep performing a version of self that no longer holds?

The Hidden Cost of Sustained Visibility

For many—particularly neurodivergent individuals—daily life involves the constant work of appearing stable, coherent, “appropriate.” This is often described as masking: the continuous filtering and reshaping of one’s behavior, reactions, and expressions in order to meet unspoken expectations.

Masking isn’t deception. It’s a form of harm reduction. A strategy for moving through systems that rarely make space for complexity, sensitivity, or non-normative ways of thinking, relating, or being.

But the cost is cumulative. Over time, this effort drains not only mental and emotional resources but also erodes the connection to one’s internal compass. Eventually, the question shifts from “How do I keep this up?” to “Why am I doing this at all?”

When the performance can no longer be sustained, disappearing can become the most coherent, least violent option available. Not an act of hiding, but of choosing not to fracture further.

Re-Evaluating the Departures

Some historical exits begin to look different when read through this lens:

Simone Weil: Her shift from academic philosophy to factory labor is often remembered as an act of radical solidarity. But it may also reflect a need to escape the disembodied, hyper-rational demands of academia—a move toward a form of life that felt less extractive.

T. E. Lawrence: After becoming “Lawrence of Arabia,” he reenlisted under false names and disappeared from the public eye. Perhaps this wasn’t retreat, but relief—a way to shed a mythologized identity that no longer felt survivable.

Herman Melville: After Moby-Dick was largely ignored, Melville left the literary world for a quiet post in customs. His story is often framed as defeat. But maybe it was simply a decision to stop contorting his vision to match market expectations.

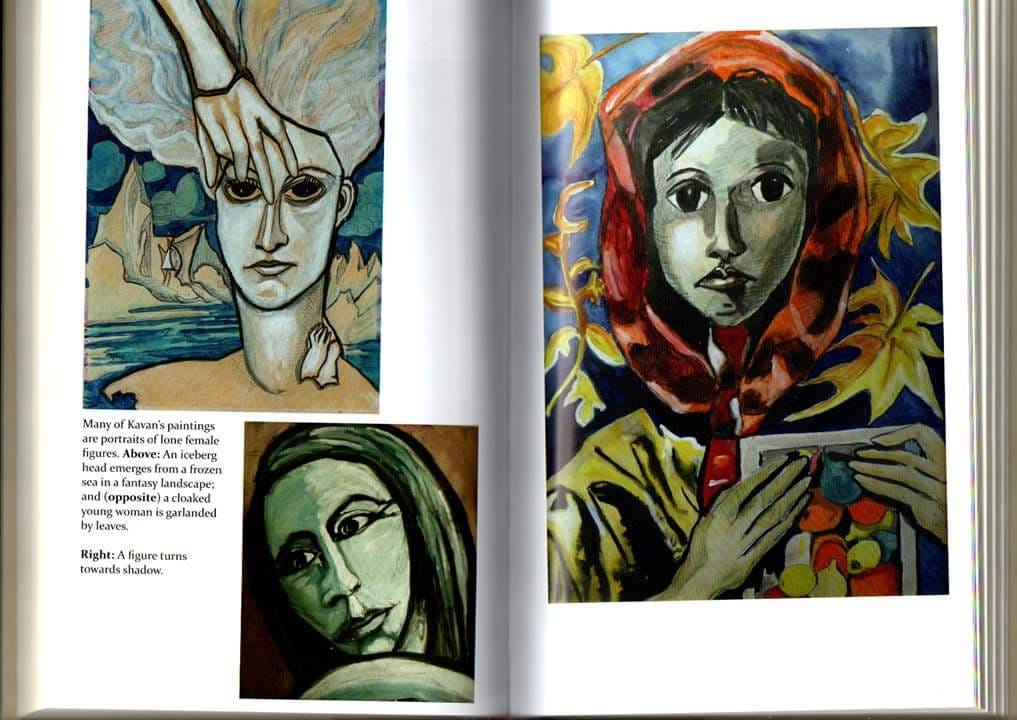

Anna Kavan: Born Helen Ferguson, she later took the name of a character she created. Rather than a sign of breakdown, perhaps it was a way of discarding an inherited self that never felt like hers to begin with.

These were not necessarily people who “gave up.” They might have been people who gave themselves permission to stop pretending.

Modern Echoes of Disappearance

We see similar patterns today. People abruptly leave high-status jobs, delete their online presence, or quietly exit communities they once helped build. These acts are often seen as unstable, even self-destructive. But more often, they follow years of invisible labor—emotional, cognitive, sensory—to remain in spaces that never felt safe or affirming.

There’s often no public crisis. No dramatic event. Just the slow, private realization: continuing to be seen requires too much suppression. The cost of presence begins to outweigh the benefit.

In such moments, disappearing doesn’t signal collapse. It signals clarity. It’s not an absence of care, but the limits of endurance.

What We Ignore

These stories point not only to individual burnout, but to collective blind spots—places where our institutions and norms fail to recognize the toll of constant adaptation.

Workplaces: We praise those who go the extra mile, but often ignore the quieter forms of overextension—especially those rooted in masking and people-pleasing. Burnout doesn’t begin when someone walks out. It often begins the first time they feel they cannot say no.

Schools: We equate good behavior with well-being, yet many students who seem to be thriving are pushing themselves to conform in ways that slowly disconnect them from their needs and identity.

Social movements: We speak of collective care, but often create environments that reward hyper-engagement and punish slowness, silence, or dissent. Alignment becomes performance, and participation becomes pressure.

Everyday life: We admire composure and stability, but rarely make room for people to show up unrehearsed. We tolerate authenticity only when it is polished and digestible.

We’re attuned to the moment someone leaves. But we rarely ask what it took for them to stay as long as they did.

Shifting Toward Empathy

Not every disappearance is rooted in neurodivergence. Not every retreat is intentional. But many of them reflect a similar threshold—the moment when the performance of normalcy becomes unsustainable.

We don’t need to pathologize these moments. Nor do we need to romanticize them.

We need a vocabulary that allows for exits that are neither collapses nor triumphs—just honest reckonings with reality.

Instead of asking, “Why did they leave?”, we might begin by wondering, “What did it cost them to remain?” And what might have changed if the environment had asked less of their performance, and more of their presence?

If you’ve ever needed to disappear, or watched someone you care about do so, consider the possibility that it wasn’t failure.

It may have been the most coherent, self-honoring choice available.

Not a retreat from the world, but a step away from the terms it insisted on.