The Amnesia Engine

How institutions metabolize critique, erase context, and make crisis their only teacher

Institutions rarely reject critique. They absorb it—slowly, selectively, and on their own terms. This essay traces how early warnings are processed out of relevance, why systems prefer failure to friction, and how memory becomes a threat to power.

You raised the concern early, calmly and clearly, without seeking credit. It wasn’t yet urgent, but you recognized the shape of the problem: an oversight in accessibility, signs of impending burnout, a flaw that would become costly down the line. You shared it proactively, hoping the issue could be addressed before it became harm.

People nodded. Someone thanked you. But nothing changed. The meeting ended, no action was assigned, and the timeline quietly reset itself.

Months later—sometimes longer—the issue resurfaced, this time as a crisis. Now there was a task force, a budget, a formalized response plan. The solution appeared decisive, and people praised it as timely and proactive. But your original insight—the moment when the harm was first avoidable—was erased from the official record.

This erasure is not accidental. It is systemic.

This Is Not Miscommunication

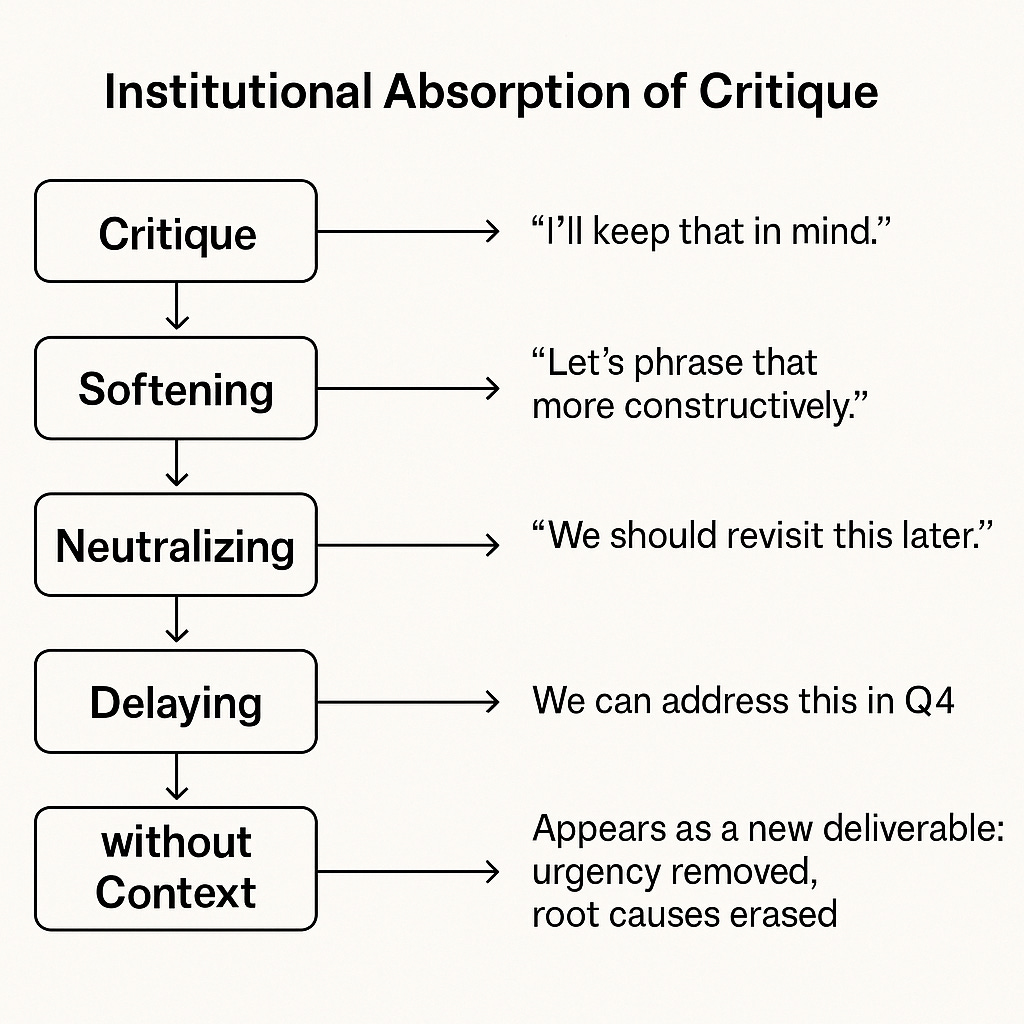

Institutional memory loss is rarely a simple oversight. It's embedded in organizational structure. Systems don’t directly reject early critique; instead, they absorb it. They convert uncomfortable insights into manageable items that fit neatly into existing priorities, workflows, and authority structures. Over time, specific concerns become softened, neutralized, reframed as mere feedback or future considerations. Eventually, they re-emerge as initiatives, stripped of the urgency and context that made them necessary.

This isn't poor communication—it's governance by forgetting. Institutions metabolize critique by delaying action until harm becomes visible enough to warrant formal acknowledgment. By then, early warnings appear irrelevant, and the delay itself is erased from the record.

Why Institutions Prefer Crisis

Institutions are structured to respond, not to anticipate. Anticipation disrupts budgets, roadmaps, and leadership narratives. Acting early requires admitting existing shortcomings.

Crisis response, however, appears authoritative and agile. By waiting for problems to escalate visibly, institutions frame delayed reaction as proactive leadership, masking structural inertia as thoughtful strategy.

Thus, the organization appears effective precisely because it waits until problems become crises—at which point solving them becomes heroic rather than simply responsible.

Institutions learn to prefer last-minute interventions over preventative adjustments, reinforcing a cycle of systemic forgetting.

Where It Appears in Practice

Examples are not hard to find, across contexts and sectors.

A disabled employee identifies barriers to access in hiring processes and is asked to wait for budget reviews.

A tenant organizer flags zoning regulations that could displace residents, only to be asked for more evidence.

Volunteers in mutual aid groups point out burnout, but leadership defers action due to capacity constraints.

In each case, early signals are not denied outright; they are quietly set aside until conditions worsen.

By the time institutions mobilize a response, the early context—the factors that initially made the issue visible and actionable—is lost. Those who raised the issue may have moved on or stopped speaking. The resulting solutions are narrower, less effective, and more costly, because the original clarity was metabolized away.

What the System Loses

The critical loss isn't just individual recognition—it’s organizational learning and preventive capability. When context is removed, solutions address symptoms without acknowledging root causes. Systems repeatedly expend resources reacting to predictable crises, rather than adapting based on early signals.

Over time, organizations become brittle. They increasingly rely on visible failures to drive action, and gradually lose sensitivity to subtle early warnings. Internal knowledge deteriorates, morale erodes, trust declines, and a pattern emerges: institutions become good at responding to problems precisely because they have lost the capacity to anticipate them.

Operational Costs

The operational cost of systemic forgetting is immense. Reactive interventions, which could have been minor adjustments, become major initiatives. Resources shift toward crisis management rather than proactive design. Institutions become faster at emergency response, but weaker at pattern recognition, losing the ability to connect early warnings with eventual outcomes.

Employees and participants who repeatedly experience the erasure of their insights learn to disengage. Eventually, many stop raising concerns entirely—not out of indifference, but out of learned institutional futility. Organizational knowledge fades, replaced by superficial "lessons learned" that omit deeper structural understanding.

Practicing Memory as a Countermeasure

You cannot force an institution to retain memory, but you can make forgetting harder.

Capture initial signals. Save the original documents, early emails, first drafts.

Note the dates. Document when concerns were first raised.

Track the language. Observe how “harm” becomes “tension,” how “exclusion” becomes “variance.”

Build timelines. Share pattern recognition across roles, not just up the chain.

Refuse resets. Don't support initiatives that erase the history of refusal they depend on.

These aren’t about assigning blame. They’re about preserving organizational intelligence.

Why Remembering Matters

If the urgency seems overdue, if solutions feel narrower than the initial warning, and if organizational responses appear reactive despite being presented as strategic—you are not mistaken.

The institution heard the early warning. It chose not to act until delay became costly. Forgetting was not an oversight but a feature of its design.

Memory is not merely documentation; it is a necessary precondition for organizational adaptability, accountability, and genuine change.

Institutions depend on amnesia because memory exposes structural inertia and delayed responses. But a system that remembers clearly—one that retains context, early warnings, and the patterns behind problems—is one capable of meaningful, preventive action.

Remembering, therefore, is fundamentally disruptive. It challenges the legitimacy of power structures built upon forgetting. It insists that problems were not inevitable, that harms were foreseeable, and that solutions are often far simpler than institutions portray.

Memory is not about individual credit—it is about collective clarity. It is the strongest defense against institutionalized forgetting.

Further reading:

When Early Detection Is Deviance — how institutions reframe early clarity as disruptive or threatening

Seemingly Neutral Systems — how procedural neutrality disguises structural erasure

Mariame Kaba, on abolitionist memory work

Sara Ahmed, on institutions reframing complaints

James C. Scott, on institutional legibility and erasure

adrienne maree brown, on fractal memory and relational timelines

Fred Moten and Stefano Harney, on institutional absorption and the politics of the undercommons