The Stock Market Hates a Cure

Ten years ago, Gilead Sciences did what modern medicine says it exists to do: it cured a disease.

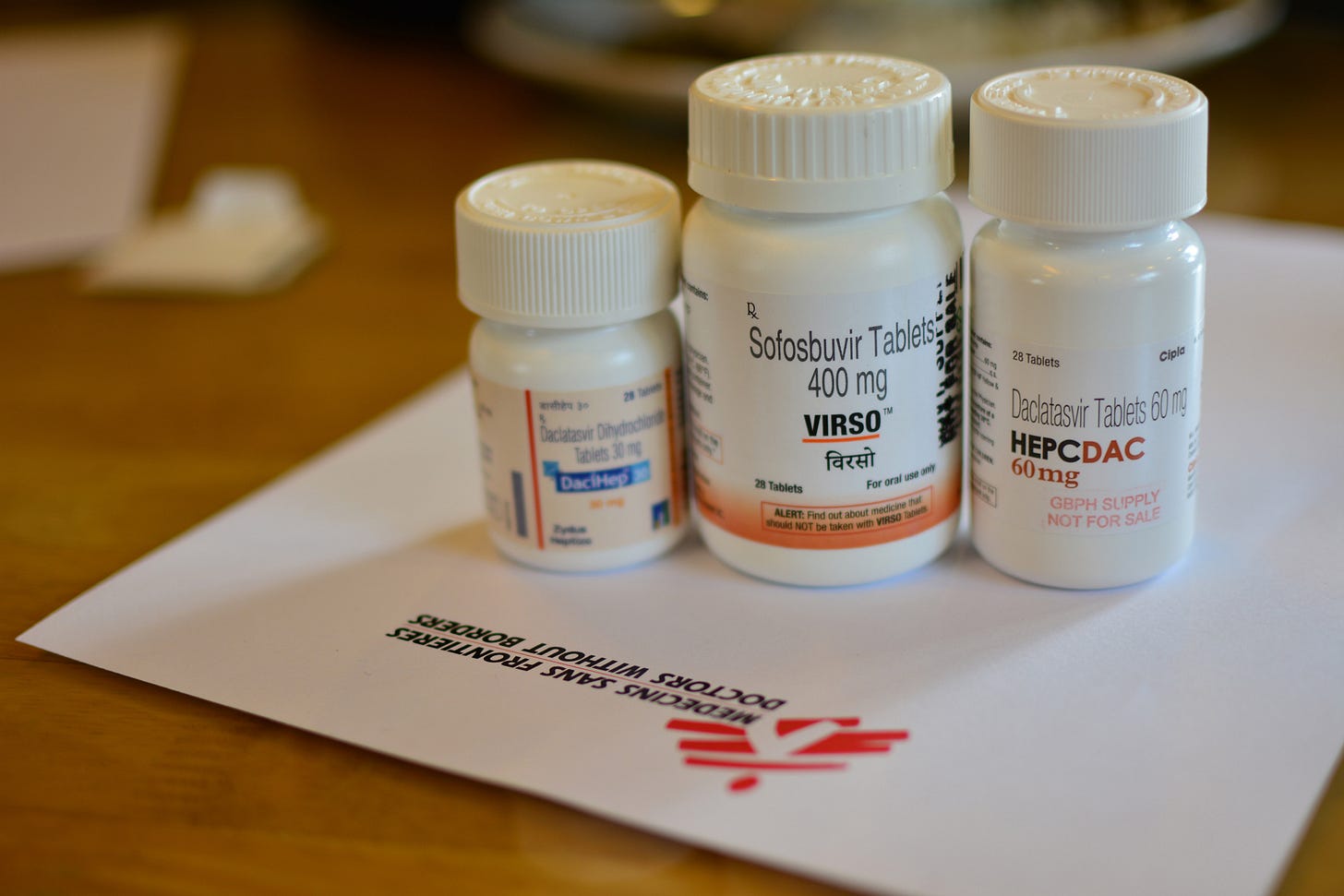

In 2013, the company launched Sovaldi and Harvoni, antiviral drugs that cleared hepatitis C in more than 90 percent of patients—in just twelve weeks, with a single daily pill. No injections. No brutal side effects. No slow burn. For clinicians, it ended a decades-long war against a virus that caused liver failure, cancer, and death. For patients, it lifted a lifetime of fatigue, shame, and fear.

For Wall Street, it triggered a sell-off.

By 2017—just two years after peak revenue—Gilead’s market capitalization had dropped by nearly $70 billion.

Not because the science failed. Not because the public lost trust. Not because of a scandal.

But because the treatment worked too well.

A product that fulfilled medicine’s highest goal—total eradication—was punished by the logic of capital.

I call this pattern the Gilead Effect:

The market-driven penalty imposed on a one-time cure that eliminates its own revenue stream—exposing the deep conflict between financial value and human health.

In 2015, Gilead’s hepatitis C franchise generated $18.7 billion in revenue—an astonishing number by any standard.

But markets don’t reward past performance. They reward predictable, repeatable, long-term cash flow. And a one-time cure, by definition, destroys its own demand. With every patient cured, the future addressable market shrank.

Analysts didn’t denounce or deny the science. They just used a more polite vocabulary:

“Finite patient pool” – too many people got better.

“Post-peak revenue cliff” – the high-water mark is already behind us.

“Non-recurring revenue profile” – no repeat purchases.

“Market-durability challenge” – growth isn’t guaranteed.

“Cure-saturation headwind” – clinical success is now a drag on returns.

None of these are critiques of the drug’s effectiveness. They’re warnings to shareholders that healing people isn’t sustainable.

The Real-World Cost of Spreadsheet Logic

For patients, this launch was deliverance. Suddenly, people who had spent decades living in fear—of infecting loved ones, of liver failure, of rejection—were cured. They could buy life insurance, apply for jobs without disclosing a condition, be removed from transplant waiting lists. For many, it was the first time in years they could imagine a future.

Clinicians went from managing slow decline to offering actual hope. But very quickly, because of the high launch price Gilead was trying to use to recoup this financially undesirable outcome, insurers reacted by implementing tight restrictions. Doctors had to prove that patients were “sick enough” to deserve the cure—despite knowing that earlier treatment would save lives and reduce costs.

Providers described the resulting moral injury as one of the most disheartening experiences of their careers.

Many of us want to blame greed. But that misses the deeper point.

Gilead’s executives weren’t doing something wrong. They were following the rules. Under shareholder primacy—the core doctrine of U.S. corporate governance—a CEO who knowingly undermines long-term company value risks personal(!) legal liability.

The problem ultimately lies in how value is measured: finance runs on discounted cash flow (DCF) models. These models assign more value to recurring, predictable income than to short, volatile windfalls. A chronic therapy that generates $1,000 per year for 20 years looks better on paper than a one-time cure that brings in $20,000 once.

Chronic illness is more financially “stable” than elimination.

No one in the boardroom had to say “Don’t cure the disease.” The math said it for them.

Today, Gilead’s experience has become a cautionary tale:

Don’t destroy your own market.

Don’t end the revenue stream.

Don’t do what Gilead did.

This logic now shapes how venture capital evaluates health startups. It nudges researchers toward treatments that manage conditions, not ones that end them. If you’re building a business case, “chronic, durable, and adherent” wins. “Curative, fast, and final” gets chopped.

That’s the Gilead Effect at work—not as a single event, but as a chilling signal to the future of medicine.

What Would a System That Wants Cures Actually Look Like?

If we want to align financial incentives with public health outcomes, we need structural change. The tools exist:

Delinkage models: Louisiana already tested a “Netflix-style” deal—paying a flat fee for unlimited cures. Pharma got its profit. The state cured thousands.

Single-payer systems: When the government pays the healthcare bills, a cured patient is a budgetary win. The incentives align.

Public or nonprofit manufacturing: Once patents expire, we can treat essential drugs like we treat bridges: as infrastructure, not profit engines.

None of these require sci-fi tech or global revolution. They just require political will and regulatory courage.

For what happens when universality is compromised—and how even single-payer models can be undermined by risk segmentation—see Beyond Deservingness.

A decade later, it’s clear: this wasn’t a one-off. This was a case study. And the lesson landed.

If you eliminate a disease, you eliminate a market. If you eliminate a market, you eliminate recurring revenue. If you eliminate recurring revenue, you eliminate shareholder value.

If we don’t change the way we value medicine, the next miracle cure may never leave the lab—not because it can’t heal, but because it heals too well.

The Gilead Effect is capitalism working with perfect, brutal clarity.

The question now is: Do we want that system writing the future of healthcare?

For more on how profit logic treats life as disposable, and what it would take to build systems that break this cycle, see:

If you want to see how these same incentives operate in housing, credit, and public benefits, start here.