Heartbroken and Devastated™

What happens when grief is routinized? When mourning scripts follow mass shootings, airstrikes, or police violence—but policy doesn’t move?

In the hours after public catastrophe, there is now a script so familiar it barely registers. A tragedy unfolds—violence, negligence, state failure—and within moments, a statement appears. It begins with heartbreak. It moves into reaffirmation. It ends with a gesture toward reflection or process.

“We are heartbroken.”

“This does not reflect our values.”

“We’re monitoring the situation.”

These phrases are never random. They are polished, preapproved, and remarkably consistent across sectors. They arrive quickly, fulfill an obligation, and disappear. They give shape to grief—but only in ways that avoid consequence.

This is not simply about corporate cowardice or bureaucratic inertia. It is about a broader system in which language functions as a stabilizer.

When something catastrophic happens, the role of the statement is to manage emotional escalation—to acknowledge feeling while displacing responsibility. In this sense, institutional grief has become something more than symbolic. It has become infrastructural.

Most public-facing organizations have some version of a crisis communications template. Copy lives in a shared drive. Names, dates, and locations are dropped in as needed.

The language follows a predictable arc: a neutral opening, a gesture of sympathy, and a vague promise of engagement.

These statements often feel sincere. Many people involved genuinely care. But the structure is not designed for change. It is designed for continuity.

The key to this language is what it avoids. Words like “tragedy,” “unimaginable,” or “incident” scrub the record clean of decisions. Grief is offered in place of authorship. Structural harm becomes ambient misfortune. You don’t have to name the contract, the budget, or the vote—only the community’s pain. The response validates emotion while buffering the institution from scrutiny.

This is most visible in moments of crisis where power is unequally distributed but rhetorically flattened.

In some of the most documented cases—police killings, bombardments abroad, deaths in custody—the language tends to move quickly toward balance.

All sides are urged to remain calm.

Both parties are called to de-escalate.

The public is asked not to politicize the moment.

Even when power is lopsided, the grief is distributed evenly. In doing so, the structure is preserved.

These statements are not empty. They do something. They offer the public a sense that the situation is under review, that someone is listening, that care is in progress.

But often, that sense of process is the product. The result is a kind of narrative closure that arrives faster than any material change. Emotion becomes the endpoint. The system that produced the harm remains untouched.

The cost of this is subtle but cumulative. Over time, we begin to associate polished grief with action, even when no action has occurred. We mistake managed language for meaningful response. We hear the tone and assume the work is underway.

In many cases, that confusion is the goal.

There are ways to say something different. The clearest statements are the least theatrical.

They name decisions.

They identify who approved what.

They describe the cost of the error and the consequence of doing nothing.

These responses tend to be rare—not because they’re difficult, but because they are unscripted. They require institutions to move beyond sentiment into something accountable. They attach sorrow to structure.

And yet, even for readers outside those institutions, the script is easy to adopt: You read a statement, you feel sadness, you keep scrolling.

There’s a sense of being present, of witnessing harm with seriousness.

But if the statement does not answer what will change, who decided what, or what happens if nothing does—then very little has been said.

It’s not that grief is wrong. It’s that grief alone, especially when deployed on schedule, can function as a kind of insulation. If the cost of public mourning is that we move on before asking why the harm happened, then the statement has done its job. Not by informing. By concluding.

The challenge isn’t to remove emotion from response. It’s to make sure that emotion doesn’t replace it.

Feeling isn’t a substitute for structure. Empathy isn’t a plan.

“Heartbroken and devastated” can be a starting point. But if that’s where it ends, then it wasn’t a response at all. It was a pause long enough to wait things out.

So when an institution appears to grieve, how do you arm yourself against the scripts they use to deflect accountability? Here’s a quick test:

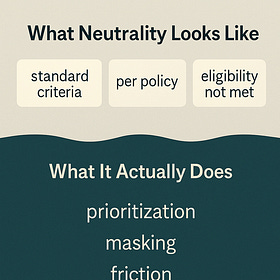

Seemingly Neutral Systems

A form doesn’t have to say “no” for a decision to be made. Sometimes the portal just stops updating. The phone call isn’t returned. The phrasing is polite: “based on our standard criteria,” or “you did not meet eligibility requirements.” No one raises their voice. No one explicitly excludes anyone. But someone has been left out.